Obama Should Model His Ukraine Policy on the Work of These Three Leaders

The 2013-14 crisis in Ukraine remains unresolved and threatens to get worse, calling to mind mid-1962, 1969, and 1984. The first earlier period found us between the Berlin Wall’s construction and the Cuban Missile Crisis. The second occurred after Soviet leader Brezhnev had sent Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia in 1968 and U.S.-Soviet relations deteriorated as we escalated the fighting in Vietnam. And the third came toward the end of President Reagan’s first term, when U.S.-Soviet relations reached another low point: he referred to the Soviet Union as the “evil empire” and “focus of evil,” and he alarmed the aged and ailing Soviet leaders by advocating his Strategic Defense Initiative, by which the USA would have established a space-based missile program that they believed threatened the USSR.

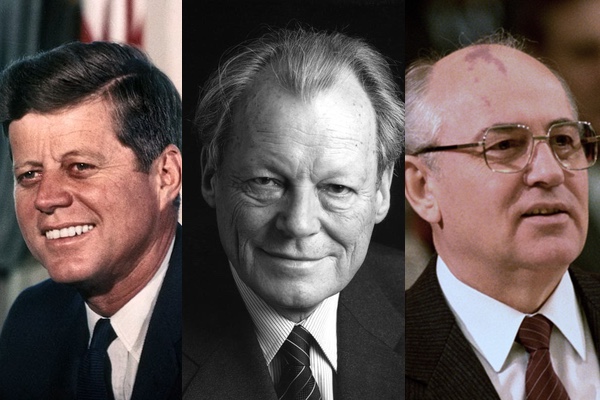

And yet in each case one year later, in 1963, 1970, and 1985, there were new signs of hope. They were mainly due to the imaginative peace policies of John Kennedy, West Germany’s Willy Brandt, and Mikhail Gorbachev.

In 2009 President Obama received the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize for “his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples” and his “vision of and work for a world without nuclear weapons.” The chairman of the Nobel Committee noted that “some people say—and I understand it—‘Isn't it premature? Too early?’ ” Regardless of whether it was “too early” or not, Obama has not, at least regarding Ukraine, justified the faith placed in him five years ago.

He has been too willing to follow hardline advice from those like the hawkish Hillary Clinton and her neoconservative Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, Victoria Nuland, who continues to help craft an unimaginative U.S. policy towards Ukraine. Instead, the president needs to follow the more imaginative examples of Kennedy, Brandt, and Gorbachev.

Although Kennedy often thought in Cold-War categories and increased the U. S. military presence in Vietnam, during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis he resisted advice to bomb Soviet missile installations in Cuba. The closeness of nuclear confrontation—according to his speechwriter and close aide, Ted Sorensen, Kennedy estimated later that the chances of a Soviet-U.S. war were then between “one out of three and even”—helped jolt JFK to more passionate peacekeeping efforts. According to Jeffrey Sachs, “Kennedy’s peace campaign found its greatest eloquence during the summer of 1963, leaving us a legacy of words and deeds of historic proportion.”

In June, Kennedy and Khrushchev established a Moscow-Washington “hot line” to facilitate emergency communications. In that same month, at a commencement address at American University, he gave the most significant peace speech of his presidency.

He referred to world peace as “the most important topic on earth,” and said “we have no more urgent task.” He recognized the “many traits the peoples of our two countries have in common,” including “our mutual abhorrence of war.” And he reminded the graduates of the tremendous losses and suffering experienced by the Soviet people during World War II.

Rather than concentrating on the flaws of the Soviet system, he counselled that we first “must re-examine our own attitude—as individuals and as a Nation—for our attitude is as essential as theirs. And every graduate of this school, every thoughtful citizen who despairs of war and wishes to bring peace, should begin by looking inward—by examining his own attitude toward the possibilities of peace.”

The pragmatic Kennedy emphasized that the peace he was advocating was not some utopian dream. It was “a more practical, more attainable peace,” based “on a series of concrete actions and effective agreements which are in the interest of all concerned.” Kennedy added that he, Khrushchev, and British Prime Minister Macmillan had agreed to have their diplomats begin discussions on a nuclear test ban treaty.

On 5 August the Test Ban Treaty was signed in Moscow, banning all but underground nuclear testing. Khrushchev was hopeful that he and Kennedy could agree on even more sweeping measures to improve U.S.-Soviet relations, but Kennedy’s assassination in November squashed his hopes.

Several additional Kennedy speeches—to the Irish Dáil, or House of Representatives (28 June), to the U. S. public (26 July,) and to the United Nations (20 September) —also indicate his increased passion for peace.

In 1969 Willy Brandt became West Germany’s chancellor. He had earlier been mayor of West Berlin and then foreign minister. In an earlier essay I quoted from his A Peace Policy for Europe (English trans., 1969) and his 1971 Nobel Peace Prize lecture, indicating the centrality of peace to his foreign policy. In the midst of the Cold War he realized that if Germany was ever to be reunited (his main goal), a more imaginative, less confrontational policy toward the USSR was necessary.

In 1970 he went to Moscow, met with Brezhnev, and signed a nonaggression treaty agreeing to existing Soviet-German boundaries. Later in the year a similar Polish-German treaty was signed. In the next two years he continued implementing his détente strategy (Ostpolitik) of improving relations with the Soviet Union and its Eastern Europe satellites including East Germany. He improved West Germany’s access to West Berlin, increased human and other contacts between East and West Berlin, and established virtually complete diplomatic relations with East Germany. By 1972, U.S. President Nixon was also pursuing a détente policy with Brezhnev.

After resigning as West German chancellor in 1974, Brandt served in the late 1970s as chairman of a North-South Commission established to address the great disparities between rich and poor countries. In his introduction to the group’s 300-page report he wrote: “If reduced to a simple denominator, this Report deals with peace. War is often thought of in terms of military conflict, or even annihilation. But there is a growing awareness that an equal danger might be chaos—as a result of mass hunger, economic disaster, environmental catastrophes, and terrorism.”

In 1990, two years before his death, the reunification of Germany occurred. In Mikhail Gorbachev’s Memoirs, the former Soviet leader refers to Brandt as “an example of wisdom, decisiveness, and responsibility in a political leader . . . the highest example of morality in politics.”

Gorbachev himself came to power in March 1985 and soon afterwards advocated a “new-thinking” foreign policy. To his credit, President Reagan responded favorably. By the end of 1988, the two leaders had met on five occasions and agreed to increased exchanges of students, cultural programs, scientific research, and nuclear testing information. The most important treaty they signed was the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, ratified in 1988, which mandated the destruction of all Soviet and U.S. intermediate land-based nuclear missiles.

After the election of George Bush Sr., Gorbachev continued his peace initiatives. In November 1990, along with twenty other NATO and Warsaw Pact leaders, the two men signed the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty, the most sweeping arms control treaty in history. It committed the signatories to destroy tens of thousands of howitzers, tanks, and other conventional weapons. In July 1991 the two leaders signed the START treaty, which promised approximately a 30 percent cut in long-range nuclear weapons over the next seven years.

In 1989 and 1990 Gorbachev also refused to send Soviet troops into Eastern Europe to prop up Communist governments. He even acquiesced in the reunification of Germany and NATO membership for the newly reunited country. By 1991 the Communist governments that had dominated Eastern Europe for decades did so no more. In 1989 Gorbachev also withdrew Soviet troops from Afghanistan, ending a decade-long Soviet occupation that had squandered more than 14,000 Soviet lives. In 1990 the Nobel Peace Prize committee awarded him its annual prize. In 1991 he refused to use military force to try to prevent Soviet republics such as Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine from becoming independent countries, and by the end of the year the USSR had disintegrated and with it his role as head of a country.

In previous posts (see, e.g., here) I have been critical of President Obama’s unimaginative policy toward Ukraine, believing it follows too much in the path of an earlier unrestrained NATO expansion policy, one that has been criticized by three men who served Republican presidents—former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, former ambassador to the USSR Jack Matlock, and former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates.

In his 2009 Nobel Peace Prize lecture Obama observed that “our common security hangs in the balance,” but that we will not “have the will, the determination, the staying power,” to achieve this security without “the continued expansion of our moral imagination.” But in a review of David Bromwich’s Moral Imagination, I quoted the author’s doubts about the president’s possession of such an imagination and his “choice of advisers utterly confined to adherents of the pro-war consensus.”

It is not, however, too late for Obama to display the imagination he called for in his 2009 speech. The continuing Ukrainian Crisis cries out for the type of leadership shown earlier by Kennedy, Brandt, and Gorbachev. While it is true that the Ukrainians themselves and other foreign leaders, especially German Chancellor Angela Merkel, have important roles to play, the U.S. stance is crucial. If Obama does not become more creative in helping to craft a solution, it is likely that the cacophony of cries to “get tougher with Putin” will grow more strident.

Former Russian ambassador Michael McFaul has stated that “The person that was always the toughest vis a vis Russia was Secretary Clinton in our inter-agency debates.” But Republicans, soon to control the Senate and fearful of her bid for the presidency in 2016, believe she was too “soft” on the Russians. Senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham have called for much greater military assistance to the Ukrainian government as it battles eastern Ukrainian separatists supported by Russia.

Some might object that Putin is like Hitler and Stalin, a man almost impossible to deal with on honorable terms. But President George W. Bush did not think so when in Moscow in May 2002 he signed with him the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT). Obama and Secretary of State Clinton did not think so in 2009, when they launched their Russian “reset” policy to improve relations after they had declined later in Bush’s presidency—true the Russian president then was Dmitri Medvedev, but Putin was prime minister and still the more dominant of the two. If Kennedy could make peace with Khrushchev, Brandt with Brezhnev, and Gorbachev with Reagan, is an honorable Ukrainian settlement with Vladimir Putin really impossible?