The Torture Debate Is Missing This: The Fact that We Did this Before

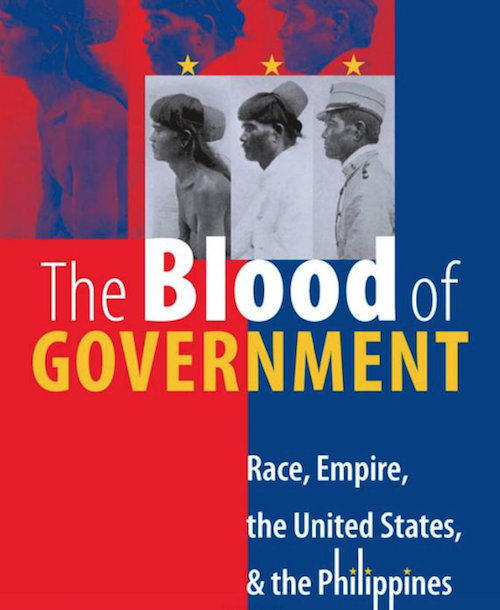

Just

over one hundred years ago, in 1902, Americans participated in a brief, intense

and mostly forgotten debate on the practice of torture in a context of imperial

warfare and counter-insurgency. The setting was the U. S. invasion of the

Philippines, a war of conquest waged against the forces of the Philippine

Republic begun in 1899. Within a year, it had developed into a guerrilla

conflict, one that aroused considerable anti-war opposition in the United

States.

The controversy was sparked when letters from

ordinary American soldiers in the Islands surfaced in hometown newspapers in

the United States containing sometimes graphic accounts of torture, and

activists within the anti-imperialist movement pressed for public exposure,

investigation and accountability. At the center of the storm was what American

soldiers called the “water cure,” a form of torture which involved the drowning

of prisoners, often but not always for purposes of interrogation.

In early 1902, the Senate Committee on the

Philippines embarked on an investigation into “Affairs in the Philippine

Islands.” While pro-war Senators on the committee tried to sideline questions

of U. S. troop conduct, anti-war Senators, working closely with

anti-imperialist investigators, provided a platform for U. S. soldiers to

testify regarding the practice of torture, including the “water cure.” Their

accounts triggered a response by Secretary of War Elihu Root that included the

minimization of atrocity and the inauguration of court-martial proceedings for

some soldiers and officers accused of torturing Filipinos.

Together, the Senate hearings and courts-martial

precipitated, by mid-1902, a wide-ranging public debate on the morality of the

U. S. military campaign’s ends and means. But the debate was over almost as

soon as it had begun since, in July 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt declared

the war concluded in victory (in the face of ongoing Filipino resistance) and

pro-war Republicans on the Senate Committee shut down the investigation.

When, during Michael Mukasey’s confirmation

hearings in the fall of 2007, the status of “water-boarding” was widely

discussed, I felt an eerie sense of familiarity. It prompted me to write an article for the New Yorker. The article did not attempt to argue that recent events are

identical to those of the early 20th century, or that the history described

here led to the present crisis. Rather, my effort was to haunt the present with

this particular, largely unknown past.

Here it is important to indicate what separates

present from past. At the turn of the 20th century, the “water-cure” was

tolerated and under-punished but was not, as far as historians are aware,

formally authorized at the highest levels in Washington. Late-Victorian

Americans also appear to have been less squeamish about the use of the word

“torture,” or were perhaps simply less seasoned practitioners of administrative

word-play, than are contemporary Americans. And at the earlier moment, the

advocates of torture did not invoke images of existential terror, such as the

diversionary “ticking time-bomb” that proponents casually lob into the present

exchange.

At the same time, past and present seem to come

together in official declarations that U. S. military actions are dictated by

the mandates of an “exceptional” kind of war against a uniquely treacherous and

broadly-defined “enemy.” And at both moments, the alchemy of exposure and

impunity produced a troubling normalization of the atrocious. Where Americans

actively defend torture, or sanction it through their silence, it is their

willingness to assimilate the pain of others into their senses of safety,

prosperity and power that stretches the darkest thread between past and

present.