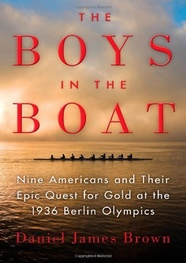

Review of Daniel James Brown's "The Boys in the Boat"

The Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and

Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, by Daniel James Brown, chronicles the University of

Washington's nine-man crew-with-coxswain's enormous success during the Great

Depression. Brown's tale is a thrilling read. This book would be of interest to

anyone interested in the history of sports, collegiate competition, Seattle and

the Northwest, America during the 1930s, and the rise of Fascism in Germany.

The Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and

Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, by Daniel James Brown, chronicles the University of

Washington's nine-man crew-with-coxswain's enormous success during the Great

Depression. Brown's tale is a thrilling read. This book would be of interest to

anyone interested in the history of sports, collegiate competition, Seattle and

the Northwest, America during the 1930s, and the rise of Fascism in Germany.

The Boys in the Boat focuses on the improbable and riveting life of Joe Rantz, and the many hardships he faced. When he entered the University of Washington as a freshman, he had already overcome enormous odds, among them extreme poverty, a fractured family, the early death of his mother, and being virtually abandoned by his father, Harry, when he was a young teenager. His journey to adulthood by itself is a truly amazing story.

Brown's writing flows effortlessly across the page, gliding the reader smoothly along, with all the grace and rhythm of, well, a rowing shell out on a clear, brisk morning. Here's how Brown describes "the most important quality" that the University of Washington's crew coach, Al Ulbrickson, looked for as he chose his boat members. In addition to "raw power, the nearly superhuman stamina, the indomitable willpower, and the intellectual capacity necessary to master the details of technique," what was needed most was "the ability to disregard his own ambitions, to throw his ego over the gunwales, to leave it swirling in the wake of his shell, and to pull, not just for himself, not just for glory, but for the other boys in the boat" (23).

After tracing Joe's utterly improbable journey to college, Brown's focus turns to the intense collegiate rowing rivalry between Washington and the University of California at Berkeley, who won gold in 1932 in Los Angeles and in 1928 in Amsterdam. In addition to defeating California, Washington would have to vanquish the accomplished Eastern crews as well in order to earn their spot in Berlin.

Here, Brown skillfully illustrates the snobbery of the Eastern crews, most from elite universities, and the contempt they held for the Western crews, whom they thought unsophisticated and uncouth. This condescension manifests itself in all sorts of ways, and makes the boys from Seattle's victories all the more satisfying to the reader.

The contrast painted by Brown between the values and ideals of Nazi Germany and the United States were equally striking. In his narrative, Brown pays special attention to Nazi propagandist film director Leni Riefenstahl's movie Olympia. I would urge the reader to go to YouTube to see clips of these powerful films, including film she took of the 1936 Olympic rowing competition itself.

Implied in Brown's enthralling tale is the notion that the 1936 Washington shell becomes a metaphor for the best that America has to offer: meritocracy, teamwork, humbleness, and true grit. Brown writes that the rowers in Washington's top shell

"had been winnowed down by punishing competition, and in the winnowing a kind of common character had issued forth: they were all skilled, they were all tough, they were all fiercely determined, but they were all good-hearted. Every one of them had come from humble origins or been humbled by the ravages of the hard times in which they had grown up. Each in his own way, they had learned that nothing could be taken for granted in life, that for all their strengths and good looks and youth, forces were at work in the world that were greater than they. The challenges that they had faced together had taught them humility--the need to subsume their individual egos for the sake of the boat as a whole--and humility was the common gateway through which they were able now to come together and begin to do what they had not been able to do before" (241).

Brown later expands upon this theme, writing that the crew

"were now representatives of something much larger than themselves--a way of life, a shared set of values. Liberty was perhaps the most fundamental of those values. But the things that held them together--trust in each other, mutual respect, humility, fair play, watching out for one another--these were also part of what America meant to all of them" (289).

The reader is swept away not only by the tale Brown tells, but the way he makes the reader feel as if he were there: rowing in the shell, out on the frigid waters of Seattle; in the minds of the rowers, full of self-doubt and anxiousness about their status on the team; in Berlin in 1936, with the Nazi Party at the height of its power. You can almost feel the extreme discomfort the rowers felt on those shells, the pain from the icicles on their hands and the lack of oxygen in their lungs.

Brown's writing is utterly majestic when describing the sheer beauty of the sport of rowing. Returning to the Washington shell house early one moonless evening finishing practice, Joe's boat slowly but steadily moved ahead of the other boats on Washington's squad. Soon, the crewmates

"couldn't hear anything at all except for the gentle murmur of their blades dipping in and out of the water. They were rowing in utter darkness now. They were alone together in the realm of silence and darkness. Years later, as old men, they all remembered the moment. Bobby Moch recalled, 'You couldn't hear anything except for the oars going in the water ... it'd be a 'zep' and that's all you could hear ... the oarlocks didn't even rattle on the release.' They were rowing perfectly, fluidly, mindlessly. They were rowing as if on another plane, as if in a black void among the stars, just as Peacock [the English-born boat builder and U.W. rowing guru] had said they might. And it was beautiful" (259).

Brown has a remarkable eye for the vivid detail, and brings the reader into the world of the 1930s with tremendous ease. As but one example, Brown's remarkably colorful and dramatic description, step by step, of the rowers spontaneous attempt while competing on the Hudson in New York to go on foot to find Hyde Park and--no, I am not making this up--try to personally meet President Roosevelt is one that the reader will long remember. Brown's writing is so clear, so suspenseful, so evocative, that the scenes cannot help but linger in the reader's mind.

Among many other things, The Boys in the Boat is a reminder that the popularity of certain sports changes over time. One hundred years ago, for example, rowing, cycling, and boxing were all hugely fashionable and were followed intensely by the general public, far more so than today.

(The decline of boxing raises the question: how long will football be king? It has dominated the sports world for the past 25 years, and has never been more popular. Might the concussion issue make football go the way of boxing? Boxing was a part of many school's physical education programs in the mid-twentieth century; does any school allow it today?)

How to explain rowing's popularity during the first part of the 20th century? As a rower friend of mine pointed out, in the early twentieth century, people had a closer relationship to boats and to water. Most all immigrants came to America by boat. Many commuted to work by boat, especially by ferries. Many transported goods by water. A greater percentage of Americans than today lived near the water. Rowing on water was something that more Americans could understand.

While Brown vividly captures America in the 1930s, and Washington's remarkable athletic achievements, this reader had wished that Brown had drawn even shaper distinctions between Hitler's Germany and FDR's America. Facing similar economic conditions, each turned to radically different types of leaders. Perhaps Brown could have touched on the reasons why each people put their faith in such diametrically opposite figures.

Brown also has a tendency to at times show-off a bit his very fluid writing skills, as there are a few slightly overly-written descriptions of the wind blowing through the rowers' hair, the whitecaps forming on the waves, and of the skill needed to shape the perfect rowing shell. And despite the extensive end notes provided, there are also a few instances when readers might question the full accuracy of all the many details of certain scenes, even if Joe Rantz did possess an almost super-human memory.

But these are very minor quibbles. Both elite and weekend-warrior athletes alike will find tremendous inspiration in Brown's tale, and will find it impossible to put the book down. The author astutely captures the nobility of athletics, and its potential to shape character among its participants.

Readers who savored Laura Hillenbrand's Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption will feel equally moved by Brown's tale of Joe Ranke and his fellow crewmates. (In fact, the hero of Hillebrand's book, the great runner Louis Zamperini, even makes an appearance in the book as the only man on the ship taking the 1936 U.S. Olympic Team across the Atlantic to Germany who could consume more food during the three daily all-you-can eat meals than Joe.)

The astonishing tale of the University of Washington's improbable quest for Olympic gold in 1936 promises to capture the attention of readers for years to come, and will stand alongside with David Halberstam's The Amateurs: The Story of Four Young Men and Their Quest for an Olympic Gold Medal, and Brad Alan Lewis's Assault on Lake Casitas, as perhaps the greatest book about rowing, or, for that matter, amateur athletics generally.