The Unbelievable Story of Kawashima Yoshiko and the Japanese Lost Soul Who Claimed He Was She in an Earlier Life

I had just finished my biography of Kawashima Yoshiko when I heard the news: Yukawa Haruna, a Japanese hostage of ISIS, had not only been gruesomely murdered, he had gone to his death convinced that he was a reincarnation of my Yoshiko.

I knew little about

Yukawa at the time, except for vague information that came my way

about his bizarre and deeply troubled life. I did, however, know

quite a lot about Kawashima Yoshiko, since I had pored over every bit

of information about her that I could find. After hearing of

Yukawa’s death, I spent some time brooding about the connection

between my biographical subject, who was executed in 1948, and the

hostage who had just died so horribly.

I knew little about

Yukawa at the time, except for vague information that came my way

about his bizarre and deeply troubled life. I did, however, know

quite a lot about Kawashima Yoshiko, since I had pored over every bit

of information about her that I could find. After hearing of

Yukawa’s death, I spent some time brooding about the connection

between my biographical subject, who was executed in 1948, and the

hostage who had just died so horribly.

While certain details of Yoshiko’s life are disputed, few doubt that she was denied serenity from start to finish. Wrenched from everything familiar at an early age, she faced dynastic upheavals and alleged sexual abuse. Born in China and raised in Japan, Yoshiko finished belonging to neither place.

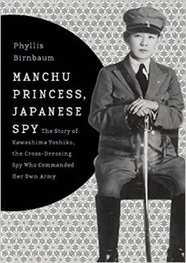

As Aisin Gioro Xianyu, she began in Beijing as the fourteenth daughter of a Manchu prince, whose legacy included unfulfilled dreams of a coup d’état and thirty-eight children. After the Manchu Qing dynasty fell in 1912, the prince plotted to bring about its return to power. His supply of children abundant, he thought nothing of giving Xianyu to a Japanese friend who promoted his political causes. As Kawashima Yoshiko, she settled down to a life in Japan, where she startled the neighbors by riding horseback, as befit a Manchu princess, to her country school. She also soaked up her adoptive father’s beliefs about how she must devote herself to bringing the Manchus back to their former glory. This goal, impelling her to storm off to battle, suited her hot, erratic temperament.

As Commander Jin, Yoshiko built a reputation as a spy who liked to dress as a man and became the heroine of a best-selling novel. With her short, handsome haircut and military uniforms, she was credited with unconfirmed exploits, among them riding horseback again, this time as leader of her own army.

If her ideas were sometimes sublime, her colleagues were not. While trying to promote the Manchus, she got involved with promoting the puppet Manchu state the Japanese had set up in Manchuria. That’s one of the reasons why Yoshiko was executed for treason in China after the Japanese defeat.

In contrast to this wild and glamorous history, Yukawa’s life was a grim saga of repeated, unnoticed setbacks. He failed at business, his wife died, he attempted suicide by cutting off his genitals. At last he decided on a new start, wandering to war zones in the hope of becoming a security expert for Japanese companies. That, of course, brought him to ISIS and his final catastrophe. By then he had taken on the feminine-sounding name “Haruna” and declared that he was the Manchu princess Kawashima Yoshiko reincarnated. To prove his point, he wrote on his blog about events in his life at age forty-one that reminded him of experiences from his former existence: “The first reports of the 9-11 terror attacks were shocking and made me remember the shock of Pearl Harbor.”

It goes without saying that Yukawa must have liked to think of himself as Yoshiko reborn because of her royal pedigree, for he, like everyone else, preferred to believe that he had been of high status in a past life rather than, say, a baker’s apprentice. The woebegone Yukawa must have also savored Yoshiko’s exotic status in Japan, for she had stood out wherever she went, a Manchu princess on horseback in the Japanese countryside, with a love of the limelight fueling her notorious reputation as ace dancer and undercover agent.

Then too there was Yoshiko’s confusion about her sexual identity, starting with her decision to cut off her hair when a teenager, some say in reaction to being raped by her adoptive father, and her vow to dress like a man from then on. “People criticize me and say that I am perverted, and maybe they’re right,” she wrote in a Japanese newspaper. “I just can’t behave like an ordinary feminine woman.” Yoshiko’s feelings resonated with Yukawa as he too tried to sort out his own sexual identity. He wrote of his ambiguous appearance, proud that he could pass for either a man or a woman. “I am of a different sex from the Yoshiko of my former life, but I have the power of a woman and also the spirit of a man. I understand the feelings of both men and women. This might be what draws people to me, even in this reincarnation.”

And then there were Yukawa’s politics, which started to veer sharply right, as he increasingly expressed sympathy for Japanese ultra-nationalists, insisting, for example, that people all over Asia were grateful for everything Japan had done for them during the Second World War. Perhaps, stretching it, one might see the echoes of his former life in his longing for a rebirth of mighty Japan, a reflection of Yoshiko’s longing for the rebirth of the Qing dynasty.

Yet the hullabaloo of Yoshiko’s existence when contrasted with Yukawa’s stifled and monochromatic days makes the karmic connection between them seem impossibly thin--until, that is, Yukawa gives up emphasizing his ties to her flashy deeds and shifts over to simple sorrow. Yoshiko’s celebrity was surely attractive to Yukawa, but he inhabited her best when he focused on the pathos of her situation, and his own. For Yoshiko, the glamorous, publicity-hungry princess, was also a lonely outsider, who had been sent away from her family in China at a young age to promote her father’s political aims and then was forced to adjust to a wretched household in Japan. “I have a home, but I cannot return,” she wrote, “I shed tears for what I cannot speak of.” Yukawa, alone and stymied, well understood her solitude and misery. “I put up a front so people won’t see how lonely and isolated I feel. Oh, I am so very lonely. Where can I go?” Yukawa wrote to prove his kinship with Yoshiko.

And who am I to doubt him?