Talking Honestly About Islamic Hate Speech

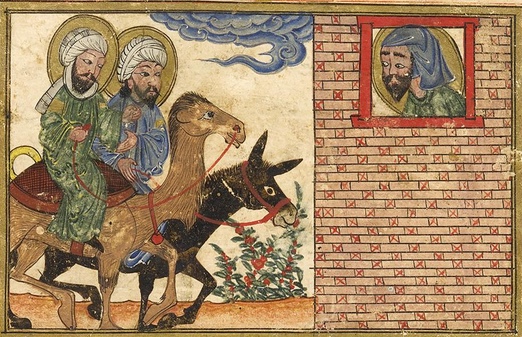

Muhammad on a camel and Jesus on a donkey

(Are images allowed?)

On May 3-4, 2015, Boston University (BU) was the site of “Apocalyptic Hopes, Millennial Dreams and Global Jihad”—a conference jointly sponsored by they BU History Department, Center for Millennial Studies (CMS) and Scholars for Peace in the Middle East. The organizer and driving force was Dr. Richard Landes, eminent scholar of medieval European (Christian) apocalyptic thought and director of the CMS until its demise in 2003. This conference, the CMS’ last hurrah as it were, brought together the dozen or so American and Israeli researchers into the topics of Muslim apolcalyptic beliefs and movements in the modern world.

Landes set the stage for the conference with his introductory lecture, In which he pointed out that Islamic apocalyptic ideas might be a “bad joke” to some, but in reality they are very “bad news.” The reason so many scholars and analysts prefer the former description is a subset of the worst problem bedeviling Islamic/Middle East studies as a whole today: the fear of the charge of “Islamophobia,” in which writing or speaking about (Islamic) hate speech is branded hate speech itself.

Landes’ position—which appeared to be the majority view among the folks attending this conference—was questioned, at times vehemently and indeed increasingly vitriolically, by several participants. The argument---which has become quite tiresome to many of us in the field, frankly—was that connecting modern jihadism and Islamic terrorism to any Islamic roots would somehow impugn all Muslims and place them at risk.

This position was ably refuted by many conference presenters, especially the journalist Graeme Wood, author of the influential article “What ISIS Really Wants” (in the March 2015 issue of The Atlantic). Wood’s presentation, entitled “On Resistance to Seeing Global Jihad as Apocalyptic Movement,” discussed the fervor and frequency with which ISIS interviewees would bring up apocalyptic Islamic ideas and how this was motivating them to behead Christians, reimpose slavery and call for attacks on Rome—and the incredulous stares which resulted whenever Wood told his (liberal) journalist friends about this. Beyond that, Wood recounted how many times interlocutors actively tried to refute his data and experience, refusing to accept that any modern Muslims—even members of ISIS—really held eschatological beliefs. (My own research into ISIS led me to conclude, last summer, that it was indeed apocalyptic.)

Dr. Jeffrey Bale, of the Monterey Institute of International Studies, lent scholarly heft to Wood’s anecdotal narrative. In particular, he focused on the phenomenon of “mirror imaging” among Westerners—the tendency to assume that the other “thinks like me,” or at least not too differently (as Wood described encountering). Thus, no matter how many times ISIS or al-Qa`idah or Boko Haram or the Taliban state, unequivocally, that they are waging jihad fi sabil Allah (“holy war in the path of Allah”), unbelieving Westerners try to explain it as really being motivated by political grievances, lack of jobs, or Western meddling in the Middle East.

Others scholars brought data and solid research to bear, on topics such as: the apocalyptic beliefs of ISIS’ predecessor group the Islamic State in Iraq; the 1979 eschatological coup manqué in Saudi Arabia, perpetrated in the name of the Mahdi (Islam’s “rightly-guided one” who will, along with the returned Muslim prophet Jesus, Islamize the planet); the nascent eschatological beliefs of Nigeria’s brutal Boko Haram movement; jihadist millennialists’ use of social media; and the apocalyptic content of Hamas’ propaganda against the Israelis.

That last topic proved a major bone of contention among the Jewish folks at the conference. At least one presenter simply hectored attendees on the blindness of many fellow Jews to see the clear Islamic roots of much of Palestianian violence—while saying nothing at all about the topic of the conference: Islamic apocalyptic thought. At least one indignant academic returned the favor, upbraiding the other side for “essentializing” all Muslims as violent (which no one at this conference had done, even implicitly)—while also ignoring the topic at hand. The vacuuity of this latter position was reached when, at the final panel, a Pakistani Muslim woman stood up and pointed out that female genital mutilation (FGM) is accepted in all four Sunni Muslim schools of jurisprudence—only to be attacked by the aforementioned panelist, who argued that FGM is only an African tribal custom. When yours truly pointed out the irony that another participant had called for “non-Muslims not to try to define Islam for Muslims”—and here a non-Muslim presenter was attacking a female Muslim—I was pilloried, as well. But having long ago left academia, I mostly found the brouhaha amusing.

My own presentation was “Rejecting Millennial Time: the Ottoman Empire’s Wars against Mahdist Movements, 13th-19th centuries.” I discussed how the foremost Sunni state of all time dealt with eschatological challenges to its rule and, sometimes, legtimacy, from state (the Twelver Shi`i Safavid Empire of Iran), non-state (“lone wolf” Sufi Mahdis) and quasi-state (Yemeni Zaydi Shi`I Imams) angles. Ottoman responses ranged from the kinetic (violent force via janissaries) and political (co-opting; limited acceding to demands) to the “soft power” of propaganda and information warfare (fatwas delegitimizing self-styled Mahdis). My major point was that modern attempts to de-fang apocalyptic groups (overt ones like ISIS; quasi-eschatological ones like Syria’s Jabhat al-Nusrah) need to emulate the Ottoman example: that is, actually employ Islamic religious texts (Qur’an, hadiths, scholarly works) to undermine eschatological jihadists (as I first called for in August 2014). Simply labeling them “non-Muslim” will not do the trick.

I first wrote about Islamic apocalyptic in 1997—the year after Landes established the CMS at Boston University—as a grad student, with an article on the famous Arab Muslim historian Ibn Khaldun and his position on the Mahdi. Over the intervening two decades, Mahdism has proved to be not just a relic of Islamic history or a narrowly Twelver Shi`i belief, but a belief deeply held by hundreds of millions of Muslims (both Sunni and Shi`i) and, increasingly, the sharp edge of the jihadist scimitar (as per Wood’s aforementioned article, and my own starting summer 2014). It’s a pity that Landes’ CMS has run its course, for as the Islamic year 1500 AH (after hijrah)/2076 AD approaches, Muslim eschatological fervor—almost certainly to include jihadist leaders thinking themselves the Mahdi—will only increase.

Note: The entire conference was recorded, and should be available to view in a week or two. Watch www.mahdiwatch.org for updates.