Did Bill Buckley Dream Up Uber Before There Even Was an Uber?

Uber is ubiquitous. From New York to Paris to Mexico City it seeks to transform personal transportation and business delivery in the face of strong opposition from taxi companies and local or state governments. But lost in the blizzard of coverage about the company’s rapid rise to global prominence is the question of who deserves actual credit for the original idea.

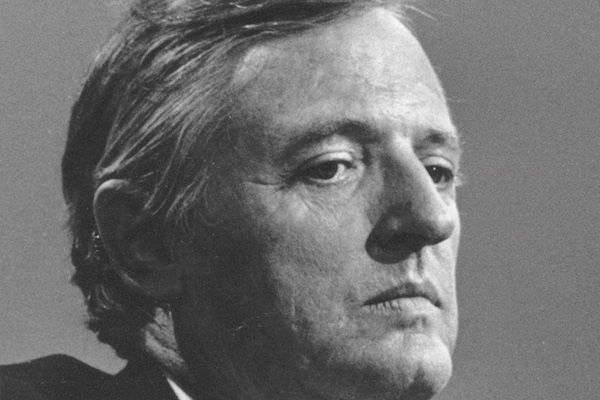

The surprising answer is the late William F. Buckley Jr., the energetic founder of National Review and the intellectual godfather of modern conservatism, who announced his candidacy for mayor of New York fifty years ago this month.

During the campaign, Buckley contended that too often liberals had delivered too many benefits to special interests or voting blocs at the expense of individual citizens. “If, for instance, you give taxi owners the right to limit the number of taxis available in the city,” he told the National Press Club, “people who need taxis to get from where they are to where they want to go can’t find taxis when they most want them.”

Buckley’s solution was to allow anyone with a driver’s license and without a criminal record to operate a car as a taxi. He also argued that passengers should have the ability to reserve a taxi by telephone for pickup at a designated time and place.

It was, in essence, the Uber concept minus the sophisticated technology. Who knows – if Buckley had won the election or taken steps to ensure that he retained the intellectual copyright for his taxi proposal his heirs might now have a legal claim or stock options.

At his introductory press conference, Buckley said that he planned to run on the Conservative Party ticket because liberal Congressman John Lindsay had already locked up the Republican nomination. Buckley also stressed that he had entered the race to promote ideas, not get votes.

When asked how many he expected to receive, Buckley quipped, “Conservatively speaking, one.” And what would you do, prodded a reporter, if you won? “Demand a recount,” replied Buckley with a grin.

But in fact he had larger ambitions. A young man – he was not yet forty – of great intelligence, wealth, and ego, Buckley hoped to deny Lindsay, a personal and political rival, the election so that conservatives could resume their march to power in the Republican Party, which the defeat of Goldwater in 1964 had interrupted.

Keeping the Democratic Party in control of City Hall also meant that liberals would retain responsibility – and receive blame – for governing New York, which was in a state of crisis due to rising crime, taxes, and unemployment as well as racial tensions from the violent unrest in Harlem and Brooklyn the previous summer.

In a column entitled “Mayor, Anyone?” Buckley disparaged Lindsay’s qualifications and his ten-point proposal to revive the city’s economy, which he ridiculed as “sheer and utter rhetorical hokum.” Buckley then introduced his own ten-point program to save New York, which he himself characterized as “half in fun.”

Some of the ideas Buckley presented were standard conservative fare, such as establishing enterprise zones in poor communities. Others were reflective of Buckley’s libertarian streak, such as legalizing gambling and drugs (for adults).

To reduce traffic congestion and promote better health, Buckley even suggested constructing an elevated bikeway twenty feet wide, which would run twenty feet above Second Avenue from 125th Street to 1st Street. Perhaps he should also receive credit for the High Line Park on Manhattan’s West Side.

Given the state of the city in 1965, opening the taxi trade to individual competition was not a priority for residents in general or Buckley in particular. Public safety – not personal transportation – was the main issue.

But in his mind yellow taxis were an important symbol of how government cartels corrupted the free market, represented state power run amok, and rewarded special interests. Buckley was, nonetheless, a pragmatist who was willing to implement his taxi plan gradually to avoid what has happened recently in New York – the “shock devaluation” of taxi medallions.

On Election Day, Buckley earned a respectable 13 percent of the votes cast after polling as high as 20 percent earlier in the fall. He came in third behind Democrat Abe Beame, the city comptroller, and Lindsay, who won and became the first Republican to occupy City Hall in twenty years.

Historians disagree as to whether Buckley ultimately helped or hurt Lindsay in the election. But they agree that 1965 was an important moment in the emergence of what Richard Nixon would later call the “Silent Majority,” as large numbers of working-class white ethnics began to desert the Democratic Party.

“Something was stirring,” wrote Buckley in The Unmaking of a Mayor, his own account of his unlikely run. He was referring to his unexpected appeal among police officers, firefighters, small-business owners, delivery men, office secretaries, elevator operators, and construction workers – “the people who made the city go” according to an aide.

But a half century later not even Buckley could have anticipated the dramatic impact that his modest proposal to reform the taxi trade has had in more than 300 cities around the world.