Their Father Was American. North Korea Won’t Let Them Go

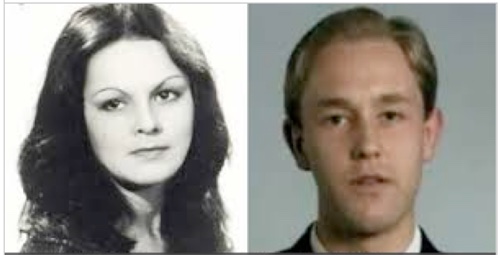

Two captives that North Korea won’t talk about — the late Doina Bumbea and her American son, James “Gabi” Dresnok.

One thing is diamond-clear about the fate of the New York University student, Joo Won-moon, who walked into North Korea of his own volition last month and was detained for entering the country illegally: he won’t be treated like two other young Americans in Pyongyang, Ted and James “Gabi” Dresnok, the sons of a GI who crossed the DMZ in 1962. The latter two have been locked inside the Hermit Kingdom their entire lives, while Joo has already been interviewed by CNN and is living in sterile luxury (for Pyongyang at least) as a celebrity hostage and most likely will be freed in months. Meanwhile, the two Dresnok boys have vanished off the face of the earth—their existence, as far as Kim Jong Un’s PR-savvy tyranny goes, a non-fact. The focus on Joo’s bizarre invasion of North Korea goes with the grain of the tyranny’s playbook; remembering the forgotten Dresnok boys does not.

Joo Won-moon, a South Korean citizen,

walked across the border in misguided hope that his actions could

make positive political waves. “I wanted to be arrested,” he told

CNN. “I thought that some great event could happen and hopefully

that event could have a good effect on the relations between the

north and [South Korea].”

Joo Won-moon, a South Korean citizen,

walked across the border in misguided hope that his actions could

make positive political waves. “I wanted to be arrested,” he told

CNN. “I thought that some great event could happen and hopefully

that event could have a good effect on the relations between the

north and [South Korea].”

Fat chance of that. Joo’s actions can have only one consequence: Giving North Korea a short-term diplomatic advantage, which will make the tyranny temporarily look less bad to the credulous. But the truth is that the North Koreans are more canny poker players in the information game than they look, as the Sony Corporation can vouch. If they know how to steal emails about the next James Bond, they know the value of a high-profile hostage—and they know that if they harm a hair on Joo’s head, it will cause them big trouble in the future.

And so Joo is being treated quite well indeed. He told CNN that he has no access to television, radio or the internet and has not been allowed to make phone calls, but that he is being fed properly, and has three beds and a private bathroom as his living accommodations. It is a story nothing like that of the grotesque and continuing suffering of Ted and James Dresnok Junior.

The story begins back in the late 1970s, when Kim Jong Il, the bouffant haired weirdo who was Kim Jong Un’s father, had scores of foreigners kidnapped. Most of the victims came from Japan. The most infamous kidnapping was that of a director and film star from South Korea, Shin Sang Ok and Choi Un Hee, who were abducted in 1978 and forced to make films for the regime until their escape in 1986. The Dresnok boys’ mother, Doina Bumbea, a beautiful Romanian artist, was a victim of a similar cruel kidnapping scam in 1978. An artist of some promise, she was living in Rome and, on the heels of a divorce that ended an unhappy marriage at 28, she was enticed by the offer of work in the art world in the Far East — she was told either Hong Kong or Japan.

The true destination was neither. Instead, Bumbea was put through a terrorist training camp near Pyongyang. (For my book, North Korea Undercover, I interviewed a former Official IRA man from West Belfast who went through the same system in 1988, learning how to kill the British from North Koreans. The IRA man hated it, and going to Pyongyang was the start of his awakening. He began to realize that no matter how badly the British were behaving in West Belfast, it was not as bad as the tyranny in North Korea.)

Bumbea was introduced to the GI defector, James Dresnok Senior; they married and soon their two sons were born. But as if the tyranny of North Korea was not bad enough, Dresnok Senior was a bully and a thug, according to Charles Robert Jenkins, a fellow GI who crossed “The Zee” in the 1960s and who, along with his Japanese kidnap victim wife, got to know the American-Romanian couple well. Jenkins was allowed to leave North Korea in 2004 and was only then able to tell the whole story. There were times when Dresnok Senior beat Jenkins, a much smaller man, to a pulp: “The sick bastard enjoyed it. He took solid, square-knuckled cracks at me across my face, one after another. Why was he always an eager torturer? He had become a stooge.”

Jenkins describes Bumbea as “beautiful and intelligent” and recalls a bleak conversation the two had in 1981, when she was still dreaming of escape to Italy. When Doina asked Bumbea, “When will I be free?” Jenkins replied, “Never.” She sold a gold necklace she’d managed to keep from Italy for a sewing machine. An excellent seamstress, she made clothes for all of the children and was a fine cook, managing to create good meals out of miserable ingredients. Her two boys grew to be strong, blond young men, European-American in looks, North Korean to listen to. They can’t be allowed to leave because they are living proof of their mother’s kidnap – a crime the state denies.

Bumbea died of cancer in 1997. Her younger son, Gabi, popped up in a 2006 documentary about Dresnok Sr. called “Crossing The Line,” but the oldest, Ted, has never been filmed. In response to inquiries by the Romanian government, officials in North Korea have denied having evidence that she was ever in the country. And still, her two sons — now in their early-30s — remain in captivity behind the curtain, locked up in the North Korean oubliette.

Unlike Joo, who willingly walked into the lion’s den, Ted and Gabi were born into it and have no way out. As an NYU student and permanent U.S. resident, Joo is getting the media coverage, but we must not forget these other victims. At some point, the State Department will organize for a member of the American nobility — a Bush, a Clinton, a Blah-Blah — or a high-level spook from Langley, to go to Pyongyang, cap in hand. The American show pony will do a bit of kow-tow and then return with Joo. A steady trickle of Korean-Americans, especially Christians, have been down this well-worn path in the past.

All will be over soon for Joo, but the story of Ted and Gabi Dresnok — and of the estimated 100,000 inhabitants of the North Korean gulag, whose starvation, torture and semi-casual killing has been told in scores of defector accounts in books such as The Aquariums of Pyongyang and Long Road Home — tells us far more about the truth of what happens beyond the 38th parallel north.