The Backstory to U2’s Record of Activism

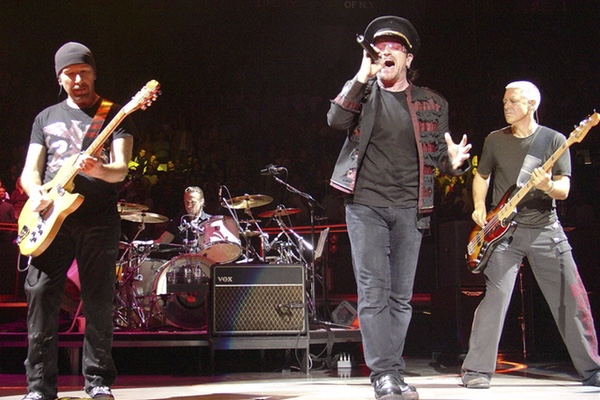

Legendary Irish rock band U2 is finishing up a triumphal tour of North America. Critics have praised the stage design, which enhances intimacy between band and fans, as well as the tour’s theme, a look back at the U2’s origins in 1970s Dublin, where poverty, punk rock, and politics ruled or riled teens like them.

The name of the tour—“Innocence +

Experience”—could also characterize the band’s evolution as

activists. Casual observers could be forgiven for thinking of U2 as

merely a “benefit” band, haranguing audiences concert after

concert about its causes. But over the decades, the band’s activism

has grown more direct and effective, and it has shown the way not

only to other musicians and celebrities but also to activists.

The name of the tour—“Innocence +

Experience”—could also characterize the band’s evolution as

activists. Casual observers could be forgiven for thinking of U2 as

merely a “benefit” band, haranguing audiences concert after

concert about its causes. But over the decades, the band’s activism

has grown more direct and effective, and it has shown the way not

only to other musicians and celebrities but also to activists.

In 1976, Paul “Bono” Hewson, Dave “The Edge” Evans, Larry Mullen, Jr., and Adam Clayton formed a high-school band with no particular worldview. They were attracted to punk rebellion, to be sure. But, as devout Christians (save for Adam), they came close to ditching rock ‘n’ roll because of its luridness. They rarely discussed politics until the 1983 release of their third album, “War.”

Innocence bordering on naïveté marked the rest of U2’s Eighties. The band’s charity work almost exclusively raised consciousness and some money. They toured for Amnesty International, recorded for the anti-apartheid movement, and moved Wembley Stadium and millions more through television with their performance at Live Aid. Sure, U2 led a revival of “message music,” absent since the 1960s. And yes, there were quantifiable victories, such as tripling Amnesty’s U.S. membership after a 1986 tour.

But had raised consciousnesses led to real improvements in human rights? Was Nelson Mandela’s release in 1990 due to letters sent by Amnesty members to the South African government? Probably not. Did the wars in Central America end because U2’s “Bullet the Blue Sky” excoriated the Reagan administration? Fat chance. Perhaps most depressing to U2 was the discovery that the impressive $200 million raised by Live Aid would fund Africa’s debt payments for a mere month.

After Live Aid, Bono and Larry discussed their activism, the drummer recalling that, for all the band’s onstage chatter, “we’ve never actually been involved in an action.” So, in the 1990s, U2 presented its followers with a paradox. While the band publicly mimicked phoniness and nihilism to counter its do-gooder image, it simultaneously dove deeper into activism through direct action. The band started taking sides in elections, from Bill Clinton’s in 1992 to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement referenda that heralded peace in Ireland.

In 1992, Bono and the boys sailed the Irish Sea to a British beach to protest the Sellafield Nuclear Processing Plant. Bono proposed moving inland, breaking a court order barring demonstrations on Sellafield property. Fellow travelers Greenpeace talked him out of it, saying it would ruin the environmental organization.

A year later, the band again had to be convinced to scale back its direct action. “If you believe in a cause you must be willing to put yourself on the line for that cause,” explained bass player Adam about the band’s intention to play in the war-besieged Bosnian capital of Sarajevo. In the end, the peril to crew and fans—not to mention the lack of power in the city!—proved too great an obstacle.

Still, little concrete resulted from Nineties direct action. No election turned on U2’s support. Sellafield went forward. And the Bosnian war dragged on mercilessly.

With those experiences in pocket, Bono, backed morally by the band, met the new millennium by embracing the role of superstar lobbyist. He targeted legislation in favor of a host of causes—debt, AIDS, trade, Africa, and more. The singer explained the loss of innocence this leap implied. “I’m tired of dreaming. I’m into doing at the moment.”

Bono’s decade entreating heads of state and billionaires to do something yielded dividends. Rich governments forgave tens of billions of dollars in loans to poor countries, which put 51 million children in school. Billions from Washington to fight HIV/AIDS helped save 9 million lives. Extreme poverty rates, Bono claimed in 2013, were halved since 1990. Unlike the Eighties and Nineties, concrete results from U2’s activism now seemed undeniable.

Many denied them. They argued that celebrities were taking over philanthropy from governments, that U2 moved around its capital to avoid paying taxes, and, most devastatingly, that aid failed to reach the poor in developing countries. U2 accepted some criticisms, rejected others.

U2’s evolution is not over. To be sure, the band still sings and lectures audiences about human suffering, whether in Burma, Haiti, or New Orleans. One website has the band supporting 22 charities and 22 causes (Bono’s numbers: 38 and 29).

But U2’s most important advance is the institutionalization of its activism. In 2004, Bono and 11 organizations formed ONE. This full-blown, permanent advocacy organization moved U2 beyond its penchant for temporary campaigns. ONE’s leadership includes establishment figures from politics and philanthropy and its experienced staff lobbies legislatures, raises funds, and produces policy briefs on topics from child hunger to corporate transparency. ONE has helped usher in activist trends such as mega-philanthropy and corporate social responsibility. It will likely outlive Bono.

Activists and fans can only hope that, with so much accumulated experience, U2 will always hold on to a bit of innocence.