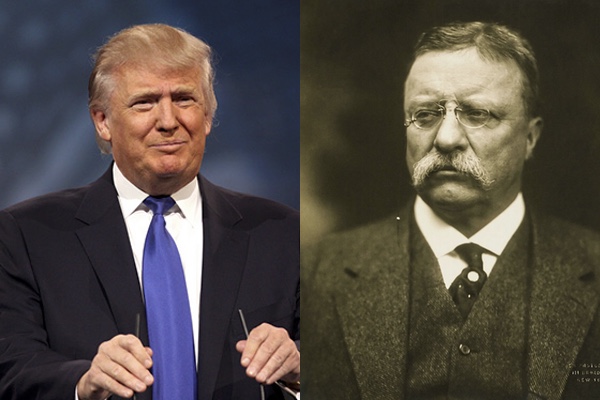

TR and Trump: Two Very Different People, but There’s this One Significant Similarity

Over one hot summer, a bombastic and wealthy New Yorker became the nation’s biggest political story. He had been in the public eye for decades, but he’d never been this much of a renegade. He drew large and passionate crowds and dominated headlines from coast to coast. At a moment when most other presidential candidates seemed uninteresting or unable to do the job, here was a mega-celebrity who promised to make America great again.

Theodore Roosevelt was to the summer of 1910 what Donald Trump became in the summer of 2015. Far from being “the silly season,” this was a critical early moment that determined the outcome of 1912 race for the White House.

The incendiary rhetoric of The Donald

prompts historical comparisons

to far-right predecessors like George Wallace and Barry Goldwater.

His lack of an internal censor recalls H. Ross Perot. He and TR have

little common ground when it comes to the substance of policy and

statesmanship. But if we really want to make sense of the Summer of

Trump – as a phenomenon of celebrity, media, and voter discontent –

we should take a closer look at the Summer of Teddy.

The incendiary rhetoric of The Donald

prompts historical comparisons

to far-right predecessors like George Wallace and Barry Goldwater.

His lack of an internal censor recalls H. Ross Perot. He and TR have

little common ground when it comes to the substance of policy and

statesmanship. But if we really want to make sense of the Summer of

Trump – as a phenomenon of celebrity, media, and voter discontent –

we should take a closer look at the Summer of Teddy.

After close to two terms as president, Roosevelt had turned the White House keys over to his old friend and ally William Howard Taft in early 1909. Then he headed out of the country. First he went big-game hunting in Africa. Next, a speaking tour of European capitals. He returned fifteen months later, more famous than ever.

When a transatlantic steamer carrying the ex-president and his entourage entered New York harbor in June 1910, hundreds of boats sailed out to greet him. On land, thousands of New Yorkers crowded the streets as Roosevelt paraded through. Banner headlines across the country proclaimed Roosevelt’s return as if he were a conquering hero. TR was the most famous man in America.

The rest of the summer built up the Roosevelt hype further. While he wasn’t a declared candidate, he certainly acted like one. He took off on a nationwide speaking tour, attracting crowds of thousands at every stop.

The ex-president barnstormed through a nation that, like today, was experiencing massive political and economic change. The rich were getting richer, the poor were getting poorer, and the middle class had got squeezed in between. Millions of immigrants – Italian, Eastern European, Russian, and more – streamed into the US, speaking alien languages, practicing different religions, and redefining what it meant to be an American. Smoke-belching factories of the new economy had replaced the family farms and workshops of the old economy. Voters were worried and angry, and looking to political leaders for answers.

The media environment changed along with it, and Roosevelt became the perfect candidate for the golden age of the newspaper. Hundreds of papers across the country had become the way millions of Americans got their news. Candidates now needed to hit the stump, to make great speeches full of quotable lines, and make headlines in as many markets as possible.

Back in the White House, President Taft became the Jeb Bush of this parallel drama: the scion of a respected political family, deeply intelligent and loyal, with close ties to GOP kingmakers. Like many nineteenth-century presidents before him, he stayed home rather than hitting the stump. He wooed party insiders, not newspaper reporters. As Taft and other establishment candidates shrunk smaller in the public imagination, the Roosevelt phenomenon gained more steam.

Like Trump, Roosevelt started talking about ideas that had long hovered on the political fringe but that hadn’t been embraced publicly by national candidates of either major party. Like Trump, Roosevelt tapped into a real hunger for change, and drew energy from existing grassroots reform movements. Like Trump, he was a master of new media: Teddy dropped one-liners on newspaper reporters like Trump blasts out tweets.

President Taft didn’t have much to say in response. He was baffled by his old friend’s resurgence, and even more confounded when Roosevelt decided to challenge him for the GOP nomination. The establishment didn’t realize that Roosevelt was more than a candidate. He was a sign that the political rules had changed.

The Summer of Teddy happened in a very different time, before television sound bites and Internet memes, before PACs and billionaire donors, before government had gotten big and attention spans had gotten short. But its lessons still resonate today, as does the lesson of the campaign’s outcome.

For the ultimate winner in November 1912 was a man few people had heard of in that summer of 1910.

Five months after Roosevelt’s triumphant sail into New York harbor, a sober-minded history professor seemingly came out of nowhere to win election as the governor of New Jersey. Two years later, Governor Woodrow Wilson was the Democrats’ presidential nominee. His had two opponents. Taft did the politics he knew the best, and worked the party machinery to win the GOP nomination. Roosevelt bolted, and ran as a third-party candidate, taking reform-hungry voters with him.

With the GOP vote split between two rivals, Wilson cruised to victory. His tactics were out of the modern playbook: charm the press, give compelling speeches, and cover lots of territory. His message was that of an outsider, promising reform and change. He sounded and acted remarkably like TR during that headline-making summer.

The lessons of 1910 apply today. Bold talk (even outrageous talk) gets traction when people want bold solutions. New media demand new tactics. Celebrities dominate when the political class can’t deliver the goods. And renegade candidates almost never win, but almost always reshape elections. The political establishment ignores them at their peril.