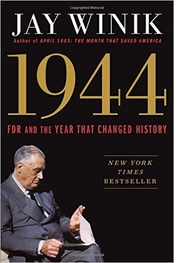

Review of Jay Winik's "1944: FDR and the Year that Changed History"

Jay Winik's 1944:

FDR and the Year that Changed History is a tour-de-force that promises to

ignite controversy for years to come regarding America's reluctance to stop, or

at least significantly retard, the Holocaust.

Jay Winik's 1944:

FDR and the Year that Changed History is a tour-de-force that promises to

ignite controversy for years to come regarding America's reluctance to stop, or

at least significantly retard, the Holocaust.

Highly readable, often beautifully written, and emotionally riveting, Winik has followed up his two highly acclaimed previous works of American history, The Great Upheaval: America and the Birth of the Modern World, 1788-1800, and April 1865: The Month That Saved America, with another book that should be read widely by the general public.

***

I must note at the outset of this review, however, that the book's title is rather odd, on a variety of levels.

First of all, each year can be said to "change" history. The title implies that 1944 changed history significantly more than other key years in the 20th century. But many other years can be said to have changed history in noteworthy ways. 1944 "changed" history in no greater way than did, say, 1929, 1933, 1939, 1941 or 1945.

The book never puts forth any real argument that 1944 changed history significantly more than other years. 1944 changed history, according to Winik, because we did not bomb the Nazi death camps, thus passing up the chance to save millions of lives. But that is different than arguing that a specific certain year itself changed history.

The title is also strangely inaccurate, because it does not describe Winik's chief argument: namely, America's moral failure regarding Holocaust, despite the fact that the U.S. government knew about the existence of the death camps, knew about the atrocities that were taking place there, and had the military capability to severely limit Hitler's ability to annihilate the Jews.

Furthermore, the book is also not really about 1944; less than half the book takes place in that year. For much of the text, 1942 seems to be the more important "year that changed history." And when it does discuss the year 1944, Winik is very selective in what he chooses to discuss about events in 1944; there is hardly any discussion of the war in Asia, for example.

And finally, though he of course figures prominently, the book is really not about FDR, either; again, the title is oddly misleading. Yes, at times Roosevelt dominates the text, but so too do Hitler and his henchmen; Churchill and Stalin; the U.S. diplomatic corps; the bureaucracy of the U.S. State Department; prominent European state officials; and even escapees from the death camps.

***

Leaving aside the very misleading title, this is simply a terrific work of military and diplomatic history.

Winik is deeply disappointed that FDR did not fully apply his enormous political skills and powers of persuasion to rally the Nation to the cause of saving European Jewry. To Winik, Roosevelt was clearly a political giant: "An astonishing blend of political genius and inspired ambition," FDR "was an aristocrat like Thomas Jefferson, a crafty politician like Abraham Lincoln, and a beloved figure like George Washington" (23). He writes that "Roosevelt was a magnet to which thousands were drawn" (45), calling him our "sermonizer in chief" (56) who "rescued democracy at home" (59).

Yet while the allied powers debated the best course of action to defeat the Nazis, millions awaited their future deaths in the camps, a delay that Winik calls an "unfathomable moral tragedy" (70).

Winik is at his best describing FDR's negotiating skills with Churchill and Stalin, revealing him as a master politician. Winik's text is especially gripping when discussing the invasion of Sicily and Italy, and D Day.

Winik's prose often sparkles:

In 1943, he writes, "At the rate of one every three seconds, another human life on earth was being snuffed out" (3).

"The logistics of Overlord were mind-numbing," he later explains. "It was as if the Allies were ferrying the entire population of Boston, Baltimore, and Staten Island–every man, woman, and child, and every car and van–in total darkness over 112 miles of choppy waters in a mere twelve hours" (81).

On election night 1944, a photographer snapped the third-time re-elected FDR as he greeted his cheering neighbors. The image shows a haggard, dying man, but "the jubilant crowd did not see what the photograph saw" (491), Winik observes.

Indeed, one particularly illuminating thread Winik weaves in throughout is his analysis of Roosevelt's health issues, especially as he approached the 1944 election, showing the president to be even more limited than many readers will have previously thought. In retrospect, it is most fortunate that FDR did not pass away before D Day (a real possibility, given his health problems); the sap on morale could have been absolutely devastating. By the spring of 1944, "The president couldn't work–work could kill him–and he couldn't not work: the country needed him" (90).

But the focus of this book is on the Holocaust, and Winik's aim is clearly to demonstrate two things: the horror and unimaginable brutality of the camps, and the American botched response to the crisis.

Winik achieves his first aim by incorporating into his narrative eyewitness accounts of the extermination camps, and the almost impossible-to-believe death-defying escape of several inmates. His graphic sections describing the extermination process promises to jar the sensibilities of even the most seasoned historian of the era. Winik writes of "the sweetish smell of burning flesh;" how slave workers "were ordered to tear open the anuses and vaginas of the cadavers to look for hidden jewelry" (100); of the "mind-numbing" amount of shoes: "They were black and gray and red, even white" (101).''

Winik soon turns his focus on Auschwitz, "the worst killing center the world had ever seen" (111), and on the April 1944 daring escape, something no Jew had successfully done before, of Rudolf Vrba and Fred Wetzler. Through them, the outside world would learn of what was going on in the camps. Later, he vividly describes the efforts of Germany's Eduard Schulte to boldly, and bravely, smuggle out of Germany details of the Holocaust; information of the horrors conveyed in the Riegner Telegram; and documentation of the atrocities in the camps given to the Allies by the Pole Jan Karski.

Winik is appalled by the State Department's inaction. "It was as though the men in Washington had covered their eyes and ears," he writes, "and were simply waiting for the whole mess to disappear" (307). Earlier in the war, FDR's leading Jewish advisor, Stephen Wise, was marginalized: "In August 1942, thanks to the State Department, Wise was still a bystander" (315). Winik argues that "The State Department remained unmoved" (118), as "the killing and dying continued" (321) and as the grisly details of Hitler's genocide made their way to the West.

Winik goes as far to charge that the State Department sent a cable in February 1943 whose "real intent was to impede the flow of information from Europe to the United States about the ongoing Holocaust" (375). While the Allies dithered, "the slaughter of the Jews continued" (383) as various diplomats' and delegations' "plan after plan was raised and rejected" (386).

In 1942 "only 2,705 Jews fleeing Nazi persecution had been admitted to" America, Winik writes, "the equivalent of one hour's worth of the gas chambers at Auschwitz" (417).

Yet Roosevelt, "the most extraordinary and enigmatic political leader perhaps on earth" (165), kept his focus on winning the war, rather than prioritize getting rid of the camps. The fate of the Hungarian Jews weighed in the balance. And following D Day, Hitler's focus on exterminating the Jews only intensified; at Auschwitz, Jews "were being gassed at the astounding rate of two thousand every thirty minutes" (201). The allies even had photos of the camp, and yet did nothing.

Key to Winik's narrative is the outsized role played by the State Department's Breckinridge Long, who Winik characterizes as an anti-Semite, and the enormous influence he had upon FDR. Obsessed with the threat of domestic spying, Long "pile[ed] up one obstacle after another to keep refugees from getting visas" (229).

Winik is at his best when describing the evolution, both theoretical and in practice, of the Final Solution. The text here is both utterly gripping and deeply disturbing.

For Winik, Roosevelt bears much of the blame for America's reluctance to aggressively hinder the Holocaust. Most of all, FDR deeply disappoints the author. After all, Roosevelt frequently showed so much raw courage.

In the political arena, we see this in his efforts to boldly arm Great Britain; in spearheading, against the advice of some of his generals, the North African invasion of Italy; in his delicate and nuanced handling of the frequently fraught Churchill/FDR/Stalin alliance; and in his enormous capability to clearly and inspiringly communicate to the American people what the war was all about.

Furthermore, on a personal level, Winik's portrait also shows Roosevelt as a man of enormous courage; always resolute, always cheerful, and never yielding to the physical limitations imposed upon him by polio.

Yet FDR "neither offered to make a speech personally denouncing the Final Solution nor offered to make it the topic of a fireside chat" (330). By the time the War Refugee Board was formed, in February 1944, "five million Jews were now dead" (434). When Germany took over Hungary in March 1944, "the stage was set for the largest single mass murder in human history–the destruction of the country's 750,000 Jews" (438). And though they had the capability to, neither the rail lines to Auschwitz nor Auschwitz itself were bombed, and Winik avers that "there is little doubt that the refusal to directly bomb Auschwitz was the president's wishes or at least reflected his wishes" (472).

Even at Yalta, in February 1945, "the fate of European Jews, both those who had been killed and those who clung to survival, was seemingly not a topic meriting consideration by the Big Three" (513). Germany's war on the Jews would continue for the final months of the war.

Winik laments that "There was no moment when [FDR] unequivocally made World War II about the vast human tragedy occurring in Nazi-controlled Europe, about the calculated effort to wipe an entire people from the earth" (533). The tragedy, to Winik, is that "Given the depth of public admiration for him ... he could no doubt have roused the American public to follow him. In 1944 he had his chances" (535).

***

The text is marred, however, by some uneven writing and editing.

In two remarkably glaring errors, Winik writes that 36 million died in World War Two, when the correct number is approximately70 to 85 million, and that 19 million civilians died, when the number is also considered far higher (532). An error/typo of such enormous magnitude is truly hard to fathom.

Winik also writes of a 1942 Nazi list of 2,284,000 Jews in Germany, far too large a number; perhaps he meant lands currently occupied by Germany?

Winik repeats the fact that George Marshall missed a meeting at Tehran because he was off sightseeing (22, 63). He repeats word for word that Hitler by the end of the war "was taking twenty-eight pills a day" (204, 358). He also repeats the phrase that in 1944 Jews "were being gassed at the astounding rate of two thousand every thirty minutes" (201 and 484).

I was surprised to see several typos.

Sometimes characters are introduced into his narrative, and then are not heard from again (most glaringly, the remarkable story of Eduard Schulte). While there are outstanding brief biographical sketches of Roosevelt and Hitler, there are, oddly, none of either Churchill or Stalin.

It would have been helpful to have introduced more maps for those readers not familiar with the intricacies of European geography, and some of the maps that were included were just too small to follow. This reader also expected to learn more about both Charles Lindbergh and the American First Committee.

Winik can occasionally talk down to the reader. Most readers know that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People is also known as the NAACP (311), or that "World War I is crucial for understanding Hitler" (endnote, 582).

And while certain government officials, especially Long, are accused of harboring virulent anti-Semitic beliefs, there is curiously little discussion about the widespread prevalence, as well as the roots, of anti-Semitism in the United States. (And though the lengthy section on the history of German anti-Semitism is highly illuminating, more would have been welcomed about the roots of such sentiments in Eastern Europe, as in his absolutely chilling description of one of the initial Lithuanian pogroms (257).). It seems that that sentiment is at the very root of American inaction, and yet it is not discussed in any great detail. This is a curious choice, as it could explain so much of the disastrous direction of American policy at the time.

And lastly, some critics might complain about the lack of major original research. But Winik has proven himself a master at synthesizing an enormously wide range of other scholarship in the field, drawing heavily from several classics: Jon Meacham's Franklin and Winston: An Intimate Portrait of an Epic Friendship; Doris Kearns Goodwin's No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt–The Home Front in World War II; H.W. Brands' Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt; James MacGregor Burns's Roosevelt: The Soldier of Freedom (1940-1945); Ian Kershaw's Hitler: A Biography; Robert Dallek's Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945; David S. Wyman's The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust 1941-1945; Richard Breitman and Allan J. Lichtman's FDR and the Jews; Charles Bohlen's Witness to History: 1929–1969 (sadly, out of print); and, especially, the seminal works of Martin Gilbert, most notably The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War.

Winik's endnotes also make for good reading, and provide a tremendous overview of the historical literature surrounding American policy towards to Holocaust.

(The same cannot be said of his oddly swaggering acknowledgments page, a virtual who-is-who list of nearly 150 movers and shakers. Everyone seems to be there: Bill Clinton and George W. Bush; four members of the Supreme Court; Harry Reid and Mitch McConnell; Martha Stewart and Elie Wiesel. And does the reader really need to know that his lunch with Bush and his dinner with Condoleezza Rice were "private?")

***

The ethical issues Winik's book raises could not be more topical, as Europe and the United States at this moment remain deeply divided over the question of accepting refugees from the war-torn Middle East.

The decision to drop the atomic bombs on Japan in 1945 is, and has been for years, a staple of American history course curriculums. Winik's book reminds us that the more consequential decision was our decisions regarding Hitler's death camps. Winik argues that this shameful episode in American history is not really even all that debatable.