Why Is the World So Crazy? Freud Can Help Us Understand.

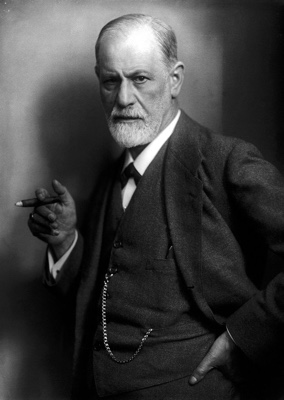

Freud by Max Halberstadt, 1921

The leading Republican candidate for President calls Mexicans rapists and his polls go up. Assault weapons are routinely used to settle workplace disputes while support for gun control plummets. The Marshall Islands and the Maldives disappear under the sea, and world leaders fail to stop global warming. Irrational mental forces are playing an out-sized role in our political and social life, but what are these forces and how can they be understood?

In the twentieth century people

struggling to understand the role of unreason in human affairs turned

to a variant of Freudian thought, distinct from psychotherapy, which

I call “Political Freud.” This was particularly the case with

progressives who struggled with racism, fascism, war, sexism and

homophobia.

In the twentieth century people

struggling to understand the role of unreason in human affairs turned

to a variant of Freudian thought, distinct from psychotherapy, which

I call “Political Freud.” This was particularly the case with

progressives who struggled with racism, fascism, war, sexism and

homophobia.

Consider, for example, WEB Du Bois. The first African-American to win a doctorate at Harvard, a founder of the NAACP, Du Bois began his career by assuming that “the Negro problem was a matter ofsystematic investigation and intelligent understanding.” Then, while teaching at Atlanta University, he encountered the knuckles of a recently lynched Black man displayed in a grocery store. Shocked, Du Bois realized, “in the fight against race prejudice, we were not facing simply the rational, conscious determination of white folk to oppress us; we were facing age-long complexes stuck now largely to unconscious habit and irrational urge.” Reconsidering his earlier views, Du Bois concluded that he had not been “sufficiently Freudian to understand how little human action is based on reason.”

Consider also the tradition of thinkers who drew on Freudian thought to understand the causes of war. During World War One, Freud explained shell shock (now known as post-traumatic stress disorder) in terms of men’s “defensive denial of vulnerability,” their “preference for the active role.” Later, the followers of Melanie Klein explained World War Two in terms of the ‘Munich’ complex, “the son’s incapacity to fight for mother and country.” More recently, to explain the irrational U.S. response to 9/11, namely the invasion of Iraq, Judith Butler pointed to the narcissistic wound opened in America by the attack, and the American inability to close that wound by mourning, collective memory, and openness to the rest of the world.

Then, too, there were the efforts of Political Freudians to fathom the destruction of European Jewry. In Moses and Monotheism, Freud tried to cast some light on the murderous rage and genocidal quality that distinguished Nazi anti-Semitism from its Christian predecessors. He argued that Hebraic monotheism had been a spiritual advance linked to the rationality and victory over the instincts at the core of the Western tradition. Still, the Hebrew people rebelled against the harsh strictures and self-denial of the original monotheistic message. Christianity sought to reconcile this conflict by the “good news” of the sacrifice of God’s son. Nazism built on Christian anti-Semitism, but went far beyond it. Attempting to create a new order or Reich, the Nazis sought to destroy the origins of the West in its founding, Hebraic encounter with God.

Finally, consider the women’s liberation and gay liberation movements of the late sixties. In that era, feminist thinkers like Kate Millett and Shulamith Firestone defined Freudianism as “the enemy.” Soon, however, other feminists, like Juliet Mitchell and Jessica Benjamin, realized that it was a mistake to throw out the baby with the bathwater. They reinterpreted Freudianism as a theory of patriarchy and used it to probe the sexual and other infantile fears that underlay sexism and homophobia. Seeking to make feminism and gay liberation something more than liberalism, they knew they needed an understanding of patriarchy’s deep unconscious. They found in political Freudianism the tools they needed.

We still need such tools today. Contemporary psychologies will not help us. Neuroscience can illuminate physiologically determined mental illnesses, such as some varieties of schizophrenia, but it has virtually nothing to say about the everyday craziness that once went under the name “neurosis,” much less the irrational patterns that run through human history. Likewise, cognitive psychology, as the psychology of rational choice, “happiness studies,” and economics, has nothing to say about the madness that runs through our political life. Today, accordingly, we still need Political Freudianism.

To be sure, there were good reasons why progressives criticized Freudianism in the 1960s and 70s and I am not suggesting that we return to discredited ideas. But it is also the case that the rise of neo-liberalism and of globalized financial capitalism was accompanied by an enormous intellectual counter-revolution, one that suppressed knowledge of both the individual unconscious and of the unconscious social and political forces that characterize modern society. My new book, Political Freud, which tells the story of these earlier struggles, aims to reintroduce one of the most important currents of modern radical thought.