The Unpleasant Facts About Carpet Bombing

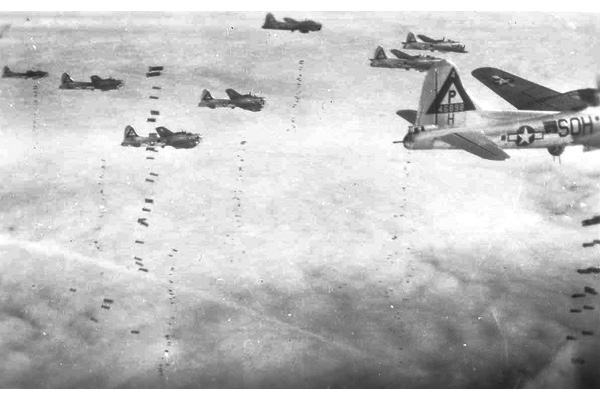

"B-17G formation on bomb run" by U.S. Air Force. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

The Republican presidential candidate Senator Ted Cruz has made it clear that in lieu of “boots on the ground” his position would be to “carpet-bomb them into oblivion.”

In a quick response, a New York Times editorial ridiculed his position pointing out that “carpet-bombing is a term used by amateurs . . . Indiscriminate bombing has never been a military strategy.” A military historian served as an expert source: “America has never carpet-bombed anyone at any time because that's not our doctrine,” declared Maj. Gen. Robert Scales, former commandant at the Army War College.

Students of air power—as well as those remaining veterans of the World War II air war –most certainly will take issue with General Scales. It is true “indiscriminate bombing” was not described as “carpet-bombing,” the official term being strategic bombing. It would, however, achieve what Senator Cruz desires: “to bomb them [the terrorists called ISIS] into oblivion.” (Candidate Trump proposed the same policy but uses a vulgar expression.)

The doctrine of “strategic bombing” dates back to the mid-1920s as a response to the terrible loss of life in the trench warfare of the 1914-1918 Great War. By the application of aerial bombardment to deter war or defeat an enemy, air power theorists believed, such losses would be avoided. Thus, the official American doctrine was affirmed in Air War Plans Division-1 of August 1941: “to conduct a sustained and un remitting air offensive (against the enemy) . . . to destroy their will and capability to continue the war.” (My emphasis.) Simply put, that goal can be met, so air power advocates firmly believed, by the bombardment from the air of enemy population centers. 500, 800, even 1,000 heavy bombers would devastate a city and in the process would destroy, not only the enemy's capability to wage war, but the will of the people to continue the conflict. (The term “carpet-bombing” was first applied in Spain's 1936-1939 civil war. Historian Hugh Thomas in The Spanish Civil War uses that term to describe an attack by German aircraft on enemy troops: “The Germans in the Condor Legion [in support of the rebel leader, Francisco Franco] tested the idea of 'carpet bombing.” [General Adolf] Galland and his friends flew in close formation, very low, up the valley, approaching the enemy from the rear. All bombs were then simultaneously released on the [enemy] trenches.” In effect the Germans were laying down a “carpet” of bombs on the enemy troops.)

Despite the utter devastation of enemy cities, American “Bomber Barons,” as they were called, insisted they were attacking military targets with “precision.” The British, however, were more honest: “The targets of the British campaign,” writes historian Donald L. Miller in Master of the Air, “ were the build-up areas of German cities, the residential centers where most of the workforce lived. . . The objective: to destroy 'the morale of the enemy civilian population and in particular, the industrial worker.' ” Be it a city bombed by the British RAF Bomber Command, or the American 8th Air Force Bomber Command, the results were similar: an utterly destroyed city with thousands of civilian causalities but limited impact on the enemy's military capability. (A distinction must be made between “strategic” air power and “tactical,” the latter being close air support of ground forces).

Strategic bombing in the Second World War included heavy losses among the bombers and bombed and proved a failed doctrine. Heavy loss of civilian lives in what was, in reality, “carpet-bombing,” both in the European conflict and in the Pacific, never induced civilians to withdraw support from their leaders. And while the bombing of military targets did indeed aid in achieving victory, especially in attacking oil production facilities, it never produced an acute shortage of military equipment. In the last year of the European war, for example, German aircraft production actually increased though of limited value due to a shortage of fuel and trained pilots.

Frederick Taylor in Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945, provides an excellent description of the British and American strategic bombing doctrine: “Perfect weather conditions, a perfect mix of high explosives and incendiary bomblets. . . all conspired to create a firestorm that ended up leveling many square miles and killing between 25,000 and 40,000 human beings.” Taylor added: “A women sent a postcard to her absent daughter. It read simply: 'All three of us still alive, city gone.'”

Yes General Scales, the American B-17 bombers were indeed precise in destroying the targeted city of Dresden (as they had Hamburg, Cologne, Berlin and many other enemy cities) in pursuit of the official doctrine of “strategic air warfare,” often called “carpet-bombing.”