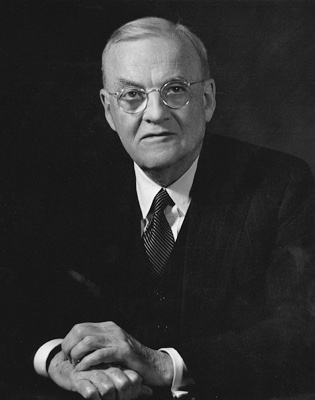

The Legacy of John Foster Dulles that Remains With Us to this Day

As secretary of state under Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 until his death in 1959, John Foster Dulles (1888-1959) animated American foreign policy with a Manichaean worldview and a powerful sense of mission inspired by his mainline Presbyterian faith. Dulles served as America’s chief diplomat at the opening of the Cold War, and in many ways he shaped the policies by which the United States carried out the Cold War until it ended with a whimper in the fall of 1991.

In terms of foreign policy, Dulles’s

American exceptionalist legacy is still very much with us. His

missionary foreign policy vision represents a stark contrast with

that of John Quincy Adams, which he

expressed when he was James Monroe’s secretary of state on

Independence Day, 1821: “[the United States] goes not go abroad, in

search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom

and independence of all.”

In terms of foreign policy, Dulles’s

American exceptionalist legacy is still very much with us. His

missionary foreign policy vision represents a stark contrast with

that of John Quincy Adams, which he

expressed when he was James Monroe’s secretary of state on

Independence Day, 1821: “[the United States] goes not go abroad, in

search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom

and independence of all.”

Dulles was convinced that America was obliged by a sacred duty to embark on a worldwide mission to defend and ensure freedom in every corner of the world. This conviction of his was informed by a belief that America was inherently good, that an enemy that was inherently evil was challenging it. Furthermore, Dulles believed that Americans were historically moved by a religious activism which was necessary, not only to their growth but also to their survival.

And most Americans continue to hold the idea that God has chosen America to fulfill a special role in world history—62 percent, according to a recent Public Religion Research Institute survey.

Dulles’s family pedigree was impressive by anyone’s standards. His mother’s relatives were diplomats and his father’s were ministers. In his maternal line (the Fosters), Dulles’s grandfather served as Benjamin Harrison’s secretary of state. His maternal uncle, Robert Lansing, served Woodrow Wilson as secretary of state. His father was a Presbyterian minister and a theologian at Auburn Theological Seminary; his paternal grandfather was a missionary to India. Through these familial influences, Dulles constructed a deeply considered, theologically informed view of America’s role in the world.

He regarded America as the most powerful force for good that the world had ever seen, contending against an adversary that threatened to plunge all of humanity into slavery. In this way, Dulles’s worldview was Manichaean. He believed that a spiritual battle was raging in the cosmos, and that America’s primary weapons were spiritual. Because of this fact, America’s material weapons were destined to prevail, but only as long as Americans remained committed to moral laws that were transcendent, absolute, and timeless.

Dulles gave a speech entitled “The Power of Moral Forces” in 1953 in which he said “[our forebears] created here a society of material, intellectual, and spiritual richness the like of which the world had never known.” In contrast, the Soviets were atheistic, ontologically materialistic, and thus, “as a result the Soviet institutions treat human beings as primarily important from the standpoint of how much they can be made to produce for the glorification of the state.” Ultimately, the difference between the United States and the Soviet Union was the difference between a religious people committed to neighbor-love and an atheistic statist system in which people were compelled to obey through the constant threat of force.

Still, because America was founded on the basis of an active, rather than a passive, religious faith, its ultimate victory over godless Communism was assured. For Dulles, America’s spiritual heritage was three-fold. In a 1947 speech entitled “Our Spiritual Heritage,” Dulles said that first, Americans’ experiment in freedom was carried out by a religious people; second, Americans historically believed that “there are eternal principles of truth and righteousness which are reflected in a moral law.” Third—and most importantly—Americans’ religious faith was fueled by a transcendent obligation to serve others. Furthermore, this commitment to look beyond themselves and to the freedom of everyone in the world was essential to the survival of the American republic. Dulles said: “our society would quickly succumb if we renounced a sense of mission in the world.”

How do we see the continuation of Dulles’s legacy in contemporary times? Certainly we can see it in manifold ways, but let us consider that legacy through the lens of the presidential candidacy of GOP Sen. Marco Rubio. Rubio has made American exceptionalism the centerpiece of his personal narrative, and by extension, his entire campaign.

This past July, Rubio sat for a question and answer session hosted by Americans for Peace, Prosperity, and Security at Furman University in Greenville, SC. What he said about American exceptionalism in general, and America’s role in the world in particular, was strikingly similar to Dulles’s vision of America’s global responsibility. “For reasons we don’t fully understand, “ he said, “America has been charged with this task of being the most influential nation on the earth.” One may wonder, who gave this charge to America? Rubio implied that the charge is God-given.

In contrast to America, which is committed to righteousness, China threatens the world with moral darkness for Rubio. He said that China “does not respect human rights,” “does not respect religious liberties,” “does not allow its people unfettered access to the internet and information.” And what happens if America were to step aside from its divine charge to lead the world? Rubio’s answer is “chaos, violence, war, radical jihadism.” Without American leadership, Rubio said that “the world will return to an age of darkness, of violence, of lack of freedoms.”

Rubio clearly believes in the moral imperative of American power and leadership, just as Dulles did in the 1950s. He divides the world into the forces of good and the forces of evil, just as Dulles did. The vision of an exceptional, indispensable America on a God-given mission is not new to Americans. But Dulles’s vision of a global mission in a Manichaean universe has become an article of faith to many Americans. It does not seem to be going away anytime soon.