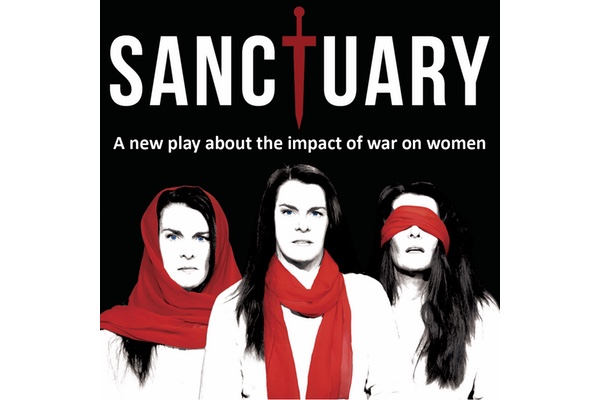

From Fredericksburg to Fallujah: Women and War

When Sanctuary begins, Susanne Sulby’s character, a laid back American housewife, is making phone calls and watching television in her kitchen. She flips from channel to channel and wars erupt on them. It is a fine beginning to a fine play about war as seen through the eyes of the women of the world.

The concept is not new and television has been overloaded with documentaries about women who fight wars, cover wars for the media and get themselves dragged into conflicts around the globe. There is something well, haunting, and electric, too, about Sulby’s new one woman show that just opened at the Lion Theater on Theater Row, W. 42d Street, in New York.

The play is more of a multi-media show than it is a drama. There is no real storyline, start or finish to it. The special effects are sensational. Director Stephen Stahl has set up television cameras and large screens on stage. In one series of vignettes, Ms. Sulby plays a woman prisoner in her cell, her emotions captured on camera and then shown on the back wall screen of the theater, as if you were watching television. Stahl also uses a large screen to show a variety of sequences from different wars, all culled from news shows and newsreel productions.

From time to time, she reverts back to a woman television reporter covering different wars, always trying to hold in her emotions as she witnesses horror after horror. She grabs a microphone and stands to the left of the screen, as if she was on the battlefield itself; it is very effective.

Her theme is that if enough people, particularly women, stand up to the governments of the world, wars can be stopped. In an interesting page of notes to the show in the program, that include the works of several anti-war poets and playwright George Bernard Shaw, she says that, statistically, violence in the world has actually gone down over the last decade or so, proving her point. Her argument is that although the earth has numerous wars, they are small in scope and cannot be compared to Vietnam or Word War II (well, you could argue that, given the civilian casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan). Therefore, she says, we need a grass roots movement to stop wars.

Sulby is a gifted actress who makes her argument in highly emotional scenes as she plays different women. She goes back in time 150 years to the U.S. Civil War and then, almost war by war, tells how women were affected by them, mostly as victims. Much of the time is spent on the Croatia conflict. She delivers her monologue as a woman describing the loss to the world from a wife or mom’s or sister’s eyes. Women do see wars differently than men, and in this play, Sulby proves it.

Sulby also wrote the play. She has come up with a moving and different, highly unique work that does make you stop and think. Her goal is not just to convert women against war but men, too. That is obvious. By observing conflicts through the feminine point of view, though, she gives the always hot issue a new look.

The play has weaknesses. It is not chronological. She bounces back and forth between World War II, the Afghan War, the Iraqi War, and goes back and forth to the American Civil War, too. You get a bit lost following the sequences of the play. She does not identify the wars that well, either, and you peer at the film footage trying to place the conflict on the screen in world history.

Overall, though, Sulby offers an often gripping, engaging and dramatic show. It could be more comprehensive and organized better, but it is pretty good. She’s right, of course. So was Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman when he said that “War is hell.”

It was then, on Sherman’s March to the Sea, and it is today, too, in Kandahar.

PRODUCTION: The handsome kitchen set, with its large screens, is nicely designed by Peter Tupitza. Costumes are by Heather Stanley, Lighting by Ryan O’Gara and sound by Howard Fredric. Stephen Stahl directs. The play runs through January 23.