This Is How Deep Racism Runs in Our History

In 1676 an English aristocrat named Nathaniel Bacon led a group of about 500 protesters into the Virginian capital of Jamestown. Agitating against the incompetent colonial governor William Berkeley, who had seemingly done little to militarily protect the Virginians, the motley assortment of working class rebels ultimately burned the capital to the ground. The Virginian leadership was horrified, not just because of Berkeley’s mishandling of the situation, but also because Bacon’s ersatz army was composed of not just white indentured servants, but African slaves as well.

It was an example of early modern, working class solidarity. Commitment to collective power distributed across the bottom rungs of the economic order did not see a color line, which was dangerous to the ruling colonial elite for whom it was in their best interest for the white working class not to acknowledge their shared interest with African slaves.

In 1741 a series of fires broke out in lower Manhattan, and a paranoia began to grip the minds of local government that the city’s large slave population (the second biggest in British North America) was conspiring with poor Irish Catholic indentured servants to burn New York down as Jamestown had been burnt down 65 years before. Historians have compared the mass panic surrounding this mysterious “Negro Plot” to the Salem witch trials, with the existence of an actual conspiracy to destroy the city about as real as the supernatural was in Massachusetts. Trials of suspected conspirators were held, and over a hundred white and black “arsonists” were executed, some of them burnt at the stake in emulation of a practice which Americans associate with the barbarity of the medieval past and not our own national history. The two accused ringleaders of the non-existent plot, an African slave named Caesar and a white tavern owner named John Hughson were killed and hung from gibbets to rot in the open air, only a short distance from where the Freedom Tower would one day rise.

In both Jamestown and New York, south and north, country and city there would be repercussions for both the real and perceived allegiance between blacks and poor whites. In the south it would lead to the strict Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, ratified in part due to events like Bacon’s Rebellion, and leading to a hardening of the legal distinctions between black slaves and their poor white allies. It was in short a solution to the ruling class’s problem – creating artificial distinctions of race would eliminate the potential of solidarity between the proletariat of various racial and ethnic groups.

It is a sobering reminder of our shameful legacy concerning race in America. The Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620, but a year before that the Jamestown colonists first purchased African slaves. The slaves were men and women who had experienced the unimaginably horrific degradations of the Middle Passage. There was slavery and racism in America before there was an America. Before the inauguration of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, early modern Europeans had a very different conception of race than subsequent generations did. It was at least initially more accommodating toward racial difference, for early modern Europeans it was religious otherness that concerned them.

But the mass importation of forcibly captured Africans began to necessitate rationalization, and so pseudo-scientific biological-based racism backed by the force of law began to coalesce as a means of justifying the slave trade. Conveniently it was also a way to prevent insurrections like the one in Jamestown, by making poor whites think of themselves as different and superior to black slaves who would have been their natural allies. From our origins Americans were sold a bill of goods, and it does us no good to pretend that the past is simply the past. Those lynched bodies rotting in the open Atlantic air in lower Manhattan are not so far removed from Eric Garner being murdered by the police.

It is common for defensive white apologists to justify away privilege by making the point that they were not directly involved in the slave trade or its associated injustices as if that were some sort of profundity. This is, of course, a cop out and obfuscation. When the very material wealth of the nation itself (in antebellum America slaves were economically the most valuable commodity) was structured and built on black bondage it is our spiritual imperative not to close our eyes and deny that heinous fact.

Charles II was the monarch who recalled Governor Berkeley from Virginia after the embarrassment of Bacon’s Rebellion. He was also the king who charted the Royal African Company (RAC) and gave it a monopoly on the English trade in African slaves, handing the reigns over to his brother and future king James II – many of the slaves imported by the RAC would be branded with “DY” for “Duke of York.” James would ultimately also give his name to that captured Dutch city at the tip of Manhattan Island. It is imperative to understand that racism in our nation has never been just a southern problem, but always an American problem.

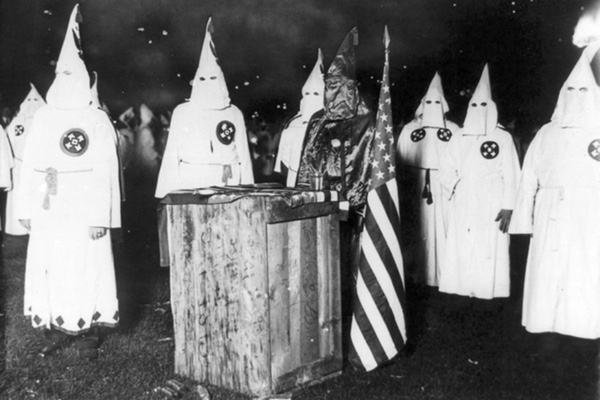

It can sometimes seem as if the charters granted to those early slaving companies have never expired. Many Americans, whether willfully or not, refuse to grasp the full scope of slavery as it legally existed from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, and the ways in which it mutated but affectively survived Reconstruction and how it continues its legacy today. And it is true that in many ways institutional racism was born out of economic justification, but the reality of racism both personal and structural cannot be reduced to economic analysis. Even if disparities in wealth were completely eliminated, and we lived in an economically just society, the original sin of racism would still sadly endure. It may have been birthed out of political expediency, but now racism is a spiritual malignancy that must be addressed as a related but distinct problem to economic injustice. This is one of the many points which Black Lives Matter, the preeminent moral movement of our era, has tried to address on the left. Again, it does us no good to deny history. We cannot abolish this cursed legacy if we refuse to even see it.

The greatest theological mind to ever occupy the office of the presidency was Abraham Lincoln, and he succinctly expressed the debts politically, economically, and spiritually accrued over the course of legal slavery. At his second inaugural address he forlornly conjectured whether the violence of the Civil War was part of America’s atonement for the introduction of race-based slavery; he said of the discord, “if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgements of the Lord are true and righteous altogether’."

A hundred years of those 250 have expired since Appomattox, I pray that we do not have to wait another 150 to see a society which lives to the best ideals of racial reconciliation. But it is for this reason that it is our moral duty to bear witness to all that was involved in the founding of this nation, and all which came after it as a result. And it is not merely to bear witness, for acknowledgment with no action is toothless, but rather it is to use our bodies and our minds as the brick and mortar for a new and just civilization. If we must work for 150 years we will work, if we must work for a millennium, we will work. For as another American theological genius, Martin Luther King Jr. said, “The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”