The 2016 Choice: A Liberal Hawk vs. America First

Related Link Sanders’ Potential Foreign Policy: An Ignored Strength? By Walter Moss

In “Clinton, ‘Smart Power’ and a Dictator’s Fall” (Feb. 28, 2016), the first of two recent New York Times articles examining her considerable record in foreign policy, Anne-Marie Slaughter, a State Department colleague, observed that:

Mrs. Clinton repeatedly speaks of wanting to be ‘caught trying.’ In other words, she would rather be criticized for what she has done than for having done nothing at all.

“She’s very careful and reflective,” Ms. Slaughter said. “But when the choice is between action and inaction, and you’ve got risks in either direction, which you often do, she’d rather be caught trying.”

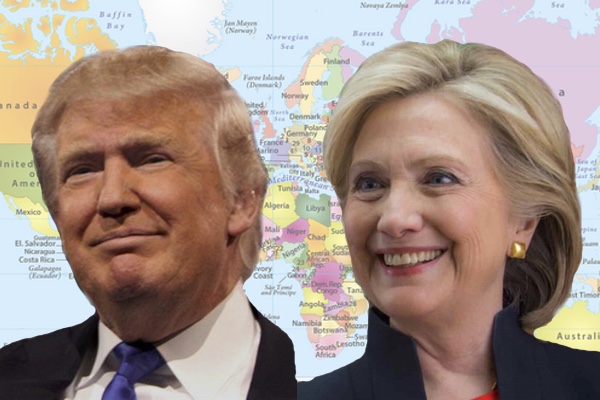

Both Times articles recount how diligent Clinton worked to arrive at her positions, but when faced with humanitarian catastrophes brought on by violent regimes or movements, she’s willing to risk the use of military force if necessary to forestall further slaughter. Her image as a “hawk,” however, is a hard sell for most Democratic voters, with her Senate vote for the 2003 Iraq invasion having cost her dearly in the 2008 contest with Barack Obama. And it could pose a problem for her in wooing a war-weary general electorate, especially if Donald Trump emphasizes his quasi-dovish isolationist views by way of contrast. As if on cue, Mark Landler’s New York Times Magazine article focused upon her relative hawkishness with its two titles: “H is for Hawk” and “How Hillary Clinton Became a Hawk” (April 21, 2016).

Yet Clinton’s advocacy of a “no-fly zone” or “humanitarian corridors” in Syria — protecting millions of displaced Syrians rather than have them flood into Europe in desperation — seems prescient. As does her advocacy of arms aid to non-Jihadi forces, which if distributed much earlier would likely have made Syria less open to ISIS and al-Qaeda than it's become. Sadly, Russia’s large-scale intervention with its air force has made the no-fly zone a more difficult proposition today.

I still see the 2011 decision to help Libyan rebels overthrow Qaddafi, with air power alone and as part of a broad coalition, as the right call — preventing a bloodbath in Benghazi as Qaddafi had promised — and applaud Hillary Clinton’s role as Secretary of State in arguing this position. Obama’s posture of “leading from behind” seemed to define an intelligent new direction for U.S. foreign policy and Western humanitarian interventionism in general. In contrast to the disastrous Bush-Cheney invasion of Iraq, even in the face of widespread international opposition, Obama’s policy was to act in concert with an array of Western and regional Arab forces, and to refrain from any major introduction of “boots on the ground.” But Obama departed from this template in Syria, most dramatically, and to the consternation of some of our allies, by backing away from air strikes in 2013 over Assad’s use of poison gas on his own people.

Undoubtedly, the mess in Libya entered into the President’s thinking. But the fault there lies collectively with the Obama administration (including Secretary Clinton) and our allies for not following through on the ground with adequate diplomatic support and technical assistance after Qaddafi’s fall.

Similarly, the Obama administration (again, including Secretary Clinton), sat on its hands as a narrow coalition of Shiite parties formed a government instead of the more inclusive coalition of Shiites and Sunnis under former prime minister Ayad Alawi, which had actually won a slight plurality of votes in the 2010 election. As the newly empowered sectarian Shiite prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki then proceeded to drive Sunni officials out of government, stopped supporting Sunni tribal militias that had been instrumental in defeating al Qaeda in 2007, and so utterly alienated Sunnis that many embraced Jihadi remnants morphing into ISIS.

We need leadership that’s careful in its application of military power. Recall President John F. Kennedy’s wisdom in imposing a naval “quarantine” of Cuba, rather than launching air attacks as advocated by his military advisers, during the Missile Crisis of 1962. But we also need a leadership that’s willing to be “caught trying,” to take measured risks, because there are no guarantees with any decision the United States may undertake in today’s increasingly chaotic world.

Rwanda descended into an incredibly rapid genocide in 1994 — for three months, probably exceeding the murderous pace at Auschwitz — partly because the Clinton administration was cowed by the “Black Hawk Down” incident in Somalia. The deaths of eighteen U.S. Army Rangers there contributed to Western inaction permitting the murder of 800,000 innocents.

And Europe tolerated two years of slaughter in the former Yugoslavia, taking a quarter million lives, until the graphic massacre of 8,000 in Srebrenica finally shamed the NATO alliance into action. NATO’s low-cost victories in Bosnia and Kosovo marked the rise of the “liberal hawks” — including such leftwing intellectuals as Kanan Makiya, Paul Berman, Michael Ignatieff and the late Christopher Hitchens — who committed the ideological heresy of supporting US military power against murderous and aggressive forces in the world.

But the cause of humanitarian intervention suffered a virtually fatal blow with the ill-advised 2003 invasion of Iraq and the dark history that followed. This was compounded by the bloody resurgence of the Taliban in Afghanistan, facilitated by the US diversion of resources to Iraq.

Chastened by these experiences, we can expect Hillary Clinton to practice a more calibrated approach to American foreign policy — one not inclined to “carpet bombing” or seeing “if sand can glow in the dark” (as Ted Cruz put it), but also not nearly as risk averse as her former boss. This would contrast with Donald Trump’s explicit promise to put “America first.”

With Trump the candidate of outspoken isolationist and white nationalist commentator Pat Buchanan, the applicability of this historic phrase is clear. Buchanan, a Republican Presidential contender in 1992 and 1996, grew up in a household that supported the original “America First” movement associated with Charles Lindbergh. Buchanan’s views endure from his childhood, as evidenced in his 2008 work of revisionist history (Churchill, Hitler and the Unnecessary War), bemoaning the Anglo-American alliance against Hitler.

Yet, since Trump often contradicts himself and tends toward bellicose pronouncements, we should wonder what he’d actually do in office (especially with his finger on the nuclear trigger). This contrasts with Clinton, who would occupy the White House as a known quantity and a reassuring presence for this country’s friends and allies.