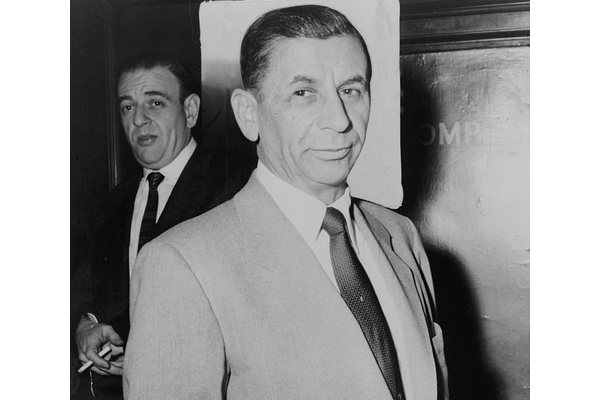

The Heirs of Meyer Lansky Want Compensation from Cuba. They Shouldn’t Get a Dime.

Meyer Lansky

The heirs of Meyer Lansky, the impresario of the North American Mafia gambling colony in Cuba (1933-1958) are betting on a big payback from the negotiations between the United States and Cuba to normalize relations between the two countries. Compensation claims by U.S. citizens or businesses for properties nationalized by the Cuban revolution are among the issues under discussion.

Lansky’s

daughter Sandi, her son Gary Rapoport, and her brother Paul have

filed a compensation claim against Cuba for the Riviera Hotel and

Casino with the U.S. Foreign Claims Settlement Commission. The Cuban

revolution confiscated the Riviera and other Mafia-owned properties

after it toppled the gangster-linked regime of General Fulgencio

Batista in 1959.

Lansky’s

daughter Sandi, her son Gary Rapoport, and her brother Paul have

filed a compensation claim against Cuba for the Riviera Hotel and

Casino with the U.S. Foreign Claims Settlement Commission. The Cuban

revolution confiscated the Riviera and other Mafia-owned properties

after it toppled the gangster-linked regime of General Fulgencio

Batista in 1959.

“It was through my grandfather’s hard work that the hotel was built,” Rapoport told the U. K. Daily Mail Online on December 23, 2015. “We are his natural relations . . . . By right, it should be our property.” He says the Riviera is valued at $70 million. The Tampa Bay Tribune, Reuters, and Haaretz have also covered the story.

The Riviera, which overlooks the Straits of Florida, was the crown jewel of Lansky’s casinos, hotels, and nightclubs in Havana. When the Riviera opened in December 1957, it was the largest Mafia-owned hotel-casino outside Las Vegas. The hotel’s 440 double rooms were booked solid for the winter season of 1957-1958.

However, the narrative that the success of the Riviera was the product of Meyer Lansky’s “hard work” is undercut by Lansky’s own assessment of his arrangement with Batista. Lansky talked candidly about his years in Cuba with Israeli national security writers Dennis Eisenberg, Uri Dan, and Eli Landau for their admiring biography Meyer Lansky: Mogul of the Mob (Paddington Press, 1979). (Lansky lived in Israel in 1970-1971 to avoid tax evasion charges in the United States.)

Lansky pitched his plan to Batista to open Mafia owned casinos and nightclubs in Cuba in 1933. Lansky promised to make Batista, who had just come to power in a coup d’etat, a partner. Batista and his inner circle would get regular payments from the Mafia gamblers. In return, the gangsters would be allowed to operate without interference from Cuban authorities. With a handshake and an abrazo, Lansky and Batista laid the foundations of the Cuban gangster state.

“Working on the well-known principle that it’s better to use other people’s money than your own, Lansky persuaded Batista to have the Cuban government help finance the venture,” Eisenberg, Dan, and Landau wrote. “The [Cuban] government agreed to back every dollar invested on the island by foreigners with a dollar of its own and to give every hotel that cost more than one million dollars the precious prize of a gambling license . . . and the casino hotels would not have to pay Cuban taxes.”

The Riviera was one of four new hotels with casinos, which opened in Havana between 1955 and 1958. Cuban development banks subsidized 50 percent of Lansky’s $14 million Riviera project; Lansky-linked investors provided the rest. Senator Eduardo Suarez Rivas, brother of Batista’s Minister of Labor Jose Suarez Rivas, was secretary of the Compania de Hotels La Riviera de Cuba, which operated the Riviera.

The Mafia gambling colony was the cornerstone of the Cuban gangster state. The gangsters’ graft bound Batista, his inner circle, senior security officers, and the Mafia together in the defense of one of the most repressive regimes in Latin America. As a CIA report put it, “In return for the loyalty they gave him, Batista always backed his security services. In times of crisis, he often suspended civil guarantees . . . and gave the services a free hand.”

The days of the North American gangsters in Cuba were numbered when Batista fled into exile on January 1, 1959. In 1958, Fidel Castro’s July 26th Movement had denounced the Mafia radio broadcasts from its guerrilla redoubt in the Sierra Maestra for turning Havana into a center of commercialized vice - gambling, prostitution, and drugs. When Castro arrived in Havana on January 8, he vowed to “clean out all the gamblers.” The Riviera and other gangster-owned properties were nationalized, and the Mafia gamblers returned to the United States.

To regain control of its casinos, hotels, and nightclubs in post-Castro Cuba, the Mafia waged a covert war on the Cuban revolution. The gangsters regrouped with their Cuban political allies, now in exile in the United States. The Mafia subsidized Cuban exile leaders and supplied arms to Cuban exile commando groups for attacks on Cuban targets from speedy boats and small aircraft. The gangsters also plotted with the CIA to assassinate Fidel Castro.

In 1959, Lansky volunteered to arrange the assassination of Castro in a meeting with the CIA, according to Doc Stacher, a life-long Lansky associate. “He [Lansky] indicated to the CIA that some of his people who were still on the island, or those who were just going back, might assassinate Castro,” Stacher told his Israeli biographers. “Meyer Lansky thought that if Castro would be eliminated there was a good chance for Batista to make a comeback . . . He told them [CIA officers] he was quite prepared to finance the operation himself.” From 1960 to 1963, the CIA and the Mafia plotted covertly to assassinate Castro.

To portray Lansky as an aggrieved victim of Cuba is to stand history on its head. There should be no compensation for the heirs of the former Mafia gamblers in Cuba.