Review of "Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker: The Miracle of Our Continuance"

This

volume is part of a series, Catholic Practice in North America. The

editors write, “Compelling and prophetic, Dorothy Day is one of the

most enduring icons of American Catholicism.” Shortly after

her death in 1980, David O'Brien, the foremost historian of Catholic

social action, wrote in Commonweal

magazine,

that Dorothy Day was “the most significant, interesting and

influential person in the history of American Catholicism.”

Not a cardinal, not a bishop, not a man. Thirty years later, David

O'Brien stood by these words in Commonweal

on March 28, 2011. When the historian and social critic Dwight

Macdonald suggested in the New

Yorker

on October 4, 1952, that one day the Catholic Church might canonize

Dorothy Day a saint, it seemed absurd. Yet in 2012, the Catholic

bishops of the U.S. unanimously petitioned the Vatican to do just

that, and Rome has initiated the process.

This

volume is part of a series, Catholic Practice in North America. The

editors write, “Compelling and prophetic, Dorothy Day is one of the

most enduring icons of American Catholicism.” Shortly after

her death in 1980, David O'Brien, the foremost historian of Catholic

social action, wrote in Commonweal

magazine,

that Dorothy Day was “the most significant, interesting and

influential person in the history of American Catholicism.”

Not a cardinal, not a bishop, not a man. Thirty years later, David

O'Brien stood by these words in Commonweal

on March 28, 2011. When the historian and social critic Dwight

Macdonald suggested in the New

Yorker

on October 4, 1952, that one day the Catholic Church might canonize

Dorothy Day a saint, it seemed absurd. Yet in 2012, the Catholic

bishops of the U.S. unanimously petitioned the Vatican to do just

that, and Rome has initiated the process.

One does not associate the name Catholic Worker (co-founded in 1933 with Peter Maurin) or Dorothy Day with luxury, but here you have it in this book. The quality of this production is such that $40 can hardly pay the price of its manufacture, weighing two pounds and two ounces and measuring eleven and a half inches by eight and a half as it does. My son glanced at it incredulously, “A Catholic Worker coffee-table book!” Every page is heavy stock and high gloss. Still, it's a treasure to hold and behold.

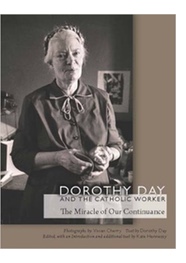

Dorothy hated to be photographed and it shows in most photos of her, with her eyes cast down, looking grim and ill at ease. But for photographer Vivian Cherry, Dorothy is the woman we knew and loved, our guide and teacher and our mother. The photos were taken in the mid 1950's, when I first came to know Dorothy. Most of the sixty photographs have never been published before. Dorothy was then in her mid-fifties and at the top of her form. She looks happy, strong and healthy though I know she had the beginnings of heart disease and was on digitalis even then. In 1970 Dorothy allowed Jon Erikson to bring his camera into the house for a book by Viking with text by Robert Coles, A Spectacle unto the Word: The Catholic Worker Movement. There are only three of Dorothy.

It is clear that Dorothy and Vivian Cherry clicked right away, which may seem strange given their different backgrounds. Dorothy was after all a Catholic convert of WASP background, a Mayflower descendant I just learned from her granddaughter Kate Hennessy, the editor of this volume. Vivian Cherry was the daughter of Jewish immigrants, an atheist and a one-time Communist. She lived on the same block on Chrystie Street as the Catholic Worker house of hospitality, just south of East Houston. But Vivian was unaware of Dorothy Day or the Catholic Worker movement until she was assigned by Jubilee magazine to take a look. She was allowed more than a look. Pacifist, anti-war (all wars!) and anti-draft, unapologetic defender of the impoverished and homeless, advocate of voluntary poverty, Dorothy guarded not only her own privacy but that of the guests on the Catholic Worker soup-line and in its house. We knew people for decades that stayed with us without ever learning their last names. They were Russian Mike and Italian Mike, Bayonne Pete, Chatty Cathy. Missouri Marie, and Mad Paul.

Dorothy's young adult life was spent in Greenwich Village's bohemian, literary scene, and on the Lower East Side, with mostly Jewish radicals. She insisted that she spent more time with the latter but that cannot be documented. She had gained an affinity with Jewish culture and so hit it off easily with Vivian Cherry. One of Dorothy's dearest friends was Mike Gold. Kate Hennessy writes that they were engaged to be married at one time. I had never heard that. I know that Dorothy loved him and was deeply grieved when Mike Gold attacked the Catholic Worker movement in an editorial in the Communist Party's Daily Worker as window- dressing for the Vatican, a Trojan horse in the house of labor. Dorothy was invited to speak at Mike Gold's memorial service in Town Hall, along with top Communist Party leaders, including Gus Hall. Everyone was told there was a strict time limit. Even Gus Hall got the hook, but not Dorothy Day. She must have gone on for twenty minutes, but she spoke of a real man of flesh and blood, not political slogans on cardboard.

The text: Dorothy Day's writing is set in Times New Roman, Kate Hennessy's in Calibri. Kate does a fine job of interpreting the CW and her grandmother's work. Dorothy's writing is always a pleasure; here it is mostly from her columns written for The Catholic Worker. I.F. Stone, Isidore Feinstein Stone, “Izzy,” came to Dorothy's funeral. Mike Harank, a community member at the time, asked him after the ceremony why, in his old age, on limited resources, he made this effort to come up from D.C., “Of all the journalists of our generation,” he said, “Dorothy Day wrote the best.”

The cover photo of Dorothy is simply beautiful. Her hair is braided and plied as a crown on the top of her head, as usual. She is looking straight into the camera, or more likely into Vivian Cherry's eyes, with a look of love. It is the way I remember her. Thanks so much to Kate Hennessy, Vivian Cherry and Fordham University Press for this treasure.