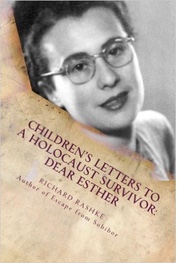

Review of Richard Rashke's "Children's Letters To A Holocaust Survivor: Dear Esther"

It

would be churlish to hold this book to the same critical standards

one might apply to an academic, historiographic or mass-market

publication on the topic of the Holocaust. There are at least two

good reasons for this "provisional suspension of critical

acuity" on the part of this reviewer.

It

would be churlish to hold this book to the same critical standards

one might apply to an academic, historiographic or mass-market

publication on the topic of the Holocaust. There are at least two

good reasons for this "provisional suspension of critical

acuity" on the part of this reviewer.

First, the subject matter itself would seem to merit publication, dissemination, and permanent collection, with its documentary value serving as a baseline.

Secondly, and no less importantly, this volume would appear to stand above the book reviewer's usual kind of normative-critical criteria for humane reasons. Its contents have been lovingly collated and edited by author Richard Rashke as a memorial to Holocaust survivor Esther Terner Raab (1922-2015), one of the three hundred Jewish prisoners who initially escaped (six hundred attempted) from Sobibór extermination camp in Nazi-held eastern Poland in 1943. The two met in 1981 at an International Liberators Conference, held in Washington and sponsored by the U.S. Department of State, where Rashke, then researching his eventual book entitled Escape From Sobibór (1982), had come expressly to meet her. The widely viewed, made-for-television film based on his book, with Alan Arkin, Joanna Pacula and Rutger Hauer, would be released under the same title in 1987.

Having stated thus a sort of generic, positive inclination, however, I would like to move to the thornier side of the question of how best to review this particular, niche or "specialty" volume.

Is the reviewer of this book obligated to serve somehow as an arbiter or witness to a bibliographic ideal, according to which every worthwhile volume published--especially a book on the Holocaust--must be collected on the shelf of collective memory, no matter its quality or expense? Or rather, am I serving as a filter for a harried librarian or collections-manager attempting to purchase the most worthwhile publications on a given topic (the Holocaust, say) within a strict (and likely ever-declining) institutional budgetary allotment?

And most pertinently: if the volume under review is a lovingly conceived work revealing the life of an admirable Holocaust survivor, and therefore a sacred topic worthy of all readers' interest and respect, would it ever be acceptable to produce a review one kilowatt shy of absolutely glowing? Would writing negatively, or even reservedly, about such a book not descend to a wrong-headed disservice--or even to some kind of sin?

I pose these questions because Richard Rashke's Children's Letters To A Holocaust Survivor: Dear Esther represents just such a specialty volume, and poses just such a dilemma. In this time of shrinking hard-copy libraries, the anthropocene climate-change menace to Civilization and threats to the Book, such a niche publication might easily vanish into the yawning crevasse implied by these considerations. Behind every printed book--is there not a burning tree?

Of course, there is already one eco-solution to the librarian's "hard-copy" dilemma. Children's Letters To A Holocaust Survivor: Dear Esther is available in both printed and digital formats.

But one general truth is eternal, in every format: Insipid books create readers' fatigue. Consequently, (and this might go without saying, yet it still needs to be said): Insipid works about the Holocaust risk contributing to--Holocaust fatigue.

I will admit it here: reading more than one-hundred pages of children's letters expressing love and admiration for a Holocaust survivor begins pleasantly enough, quickly turns dreadful, and then becomes neither negative nor positive, but merely mechanical, repetitive and in the end, compulsory. As a reviewer assigned to treat the volume fairly, I am obliged to read every word in every letter carefully, even more than once. What begins as a challenge soon becomes a dreadful, onerous task; a job I imagine will take a week ends up taking three months.

As I procrastinate, I ask myself: what is the raison d'être of this book? Aside from parents and grandparents of the children involved, and perhaps the extended family of the addressee herself, who will prove interested enough actually to buy and read it? The design, typography and layout look amateurish; is the publisher--"Historic Heroines" of Warrenton, VA--just one step above a vanity press?

Moreover, it is unfortunate that the title of the volume--Children's Letters To A Holocaust Survivor: Dear Esther--does not clearly reflect, nor credit, the actual, complete contents found in the volume. For while fully two-thirds of the volume consists of the children's letters, the final third, some sixty-five pages, contains Richard Rashke's spare, provocative and powerful two-act drama entitled--Dear Esther. Yet nowhere on the front cover of the book, nor on the title page, nor on the copyright page, does one find any mention of the play's inclusion.

Upon a close and complete reading, however, Rashke's play emerges as the highlight of the entire volume, perhaps even its reason for existing. Yet the play is virtually hidden under a bushel of either the author's modesty, or editorial ambivalence about its "add-on" position following the dismaying swamp of one-hundred-plus pages of children's letters. These veer from the sweetly sincere to the painfully clichéd ("You are a role model"), from the repetitive to the strange ("What's your favorite food?"). They bear earmarks of the peremptory "prompts" given by the teacher to help writing-blocked students get started on the assigned task of writing the letter in the first place: "One thing that stood out to me most was how heartless those Nazis were." My second question is, when you were running toward the trees, did you ever think of anyone or anything as the bullet grazed your head?"

The bizarre insertion of stills from the made-for-television movie Escape From Sobibór amidst the children's letters marks another awkward, egregious design-choice by author and/or editor. Facing a perfectly focused shot of a well-nourished, impeccably dressed Joanna Pacula posed behind barbed wire, one student's letter reads, "Sometimes I wonder how closely the actors in the movie ... resembled the attitudes of the actual people. I will never be able to see any of those actors in other movies. They played their parts so well, that in my mind, they are the survivors." I would guess that this kind of confusion is precisely the opposite of the emotional effect Rashke aims to produce in members of the audience to his play.

In fact, unlike the letters, Rashke's dramatic embodiment-in-dialogue of Esther's story is hard-hitting, frank and honest. As the curtain rises, he immediately gives his characters--adults and children--two-pages of speeches consisting solely of hair-raising slurs, ending with the classic term used to defame Jews. I pictured to myself a school-auditorium audience of families, grandparents and small children, shocked to attention by the opening lines, "spoken with anger and hatred": "Spic," "Queer," "White bread," "Jap," "Gook," "Chink," "Spook," "Spade," "Slut," "Lesbo," "Nigger," "Kike," "White motherfucker" et al.

Thus, Dear Esther--the play--opens with a bang, not a whimper. It is also adventurous in form and exciting in its ambition: to represent faithfully the implications of the Holocaust in the mind of one survivor, Esther Terner Raab, "in graphic detail," as Lawrence Langer says such works should do, "so that the destruction of an entire people and its culture--what was done, and how it was done, and by whom--makes an indelible and subversive impression" on the audience: no matter how tender, young or old.

Rashke boldly creates not one, but two speaking characters named "Esther," a handful of other dreamlike characters from her past, some of whom even represent the children giving voice to their letters verbatim, along with a fluid Chorus. We realize we are witnessing Esther's interior dialogue--in a dream, a meditation, a memory?--and by its conclusion we realize that we have witnessed the one compelling piece of the entire volume.

For it is the play Dear Esther, not the children's letters, that represents the nugget of value for which librarians might most readily purchase and shelve this book, for purposes of staged readings, individual lending--and yes, the collective memory of the Holocaust, as it merits preservation. The letters should have been left in the drawers of those who sent and received them, as private correspondence between individuals, not examples to be turned into items, nor as "testimony" to anything larger than a meaningful, yet private moment.

Near the conclusion of his seminal collection of essays Admitting the Holocaust, Lawrence Langer writes: "Sweetening the horror of the Holocaust has become the pastime of so many students of the subject that they are too numerous to list. Readers return to these sources like bees to their hive, because the honeyed vision they find there seems so savory to their moral taste buds." I am certain that Richard Rashke's intent was not to reinforce this tendency with the children's letters; the moral vision and integrity of his play proves it. Unfortunately, the tough-minded inhumanity invoked by the play Dear Esther has been buried in this volume under a polite mass of epistolary good intentions.