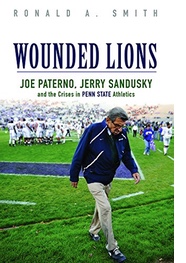

Review of Ronald A. Smith’s "Wounded Lions: Joe Paterno, Jerry Sandusky, and the Crisis in Penn State Athletics"

As

we move toward another college football season, the cautionary tale

of Joe Paterno and the collapse of the “grand experiment,” in

which Penn State University and its legendary coach asserted that it

was possible to have both academic integrity and a national

championship football program, should give us pause. Flaws in Penn

State athletics, however, were exposed not by recruiting violations

but rather through a sex scandal involving assistant coach Jerry

Sandusky and the abuse of young boys involved with the coach’s

Second Mile charity program. It is not a pretty story, but it is

told with considerable compassion in Wounded

Lions

by Penn State sport historian Ronald Smith who makes extensive use of

university archives to document how Penn State lost control of its

athletic program, and how Paterno played a key role in this process.

As

we move toward another college football season, the cautionary tale

of Joe Paterno and the collapse of the “grand experiment,” in

which Penn State University and its legendary coach asserted that it

was possible to have both academic integrity and a national

championship football program, should give us pause. Flaws in Penn

State athletics, however, were exposed not by recruiting violations

but rather through a sex scandal involving assistant coach Jerry

Sandusky and the abuse of young boys involved with the coach’s

Second Mile charity program. It is not a pretty story, but it is

told with considerable compassion in Wounded

Lions

by Penn State sport historian Ronald Smith who makes extensive use of

university archives to document how Penn State lost control of its

athletic program, and how Paterno played a key role in this process.

To understand what happened to his beloved university, Smith does not focus simply on Paterno and Sandusky, but provides his readers with an overview history of intercollegiate athletics at Penn State University. Smith observes that in the effort to obtain both a national reputation for academics as well as sport, especially football, there was considerable effort by the alumni, board of trustees, faculty, and university presidents to maintain some degree of control or at least oversight regarding the athletic program. The fact that Penn State was able to avoid the sporting scandals that plagued other university athletic programs was due to the placement of athletics within the physical education department, and, thus, athletics were not isolated from the everyday governance of the university.

This organizational structure, however, changed in 1980 when Penn State President John Oswald offered Paterno the position of athletic director in addition to maintaining his head football coaching duties. Paterno would only accept the position if the athletic department was separated from the interference and monitoring of the physical education administrators and faculty. Smith is critical of President Oswald for agreeing to Paterno’s demands without even consulting the Board of Trustees regarding this significant change in university governance. Guidance of athletics was now under the control of Paterno. According to Smith, the separation of athletics from university oversight and placement within an isolated business environment was the pivotal moment for Penn State. Smith writes: “This covert and academically disturbing coup d’état of athletic control significantly isolated Penn State athletics away from any watchful eye of academic control. The power grab, more than other single action, placed athletics in an insular division of Penn State, a financial, not an academic, arm of the university. . . . The removal and isolation of athletics from academics may very well have contributed to questionable if not illegal actions taken by individuals at Penn State in the Sandusky Scandal” (75).

As for Paterno’s motivation in initiating this power grab, Smith points to the head coach’s frustration following Penn State’s defeat by Alabama in the 1979 Sugar Bowl contest. Following this institutional change, Paterno asked President Oswald to allow one-third of the incoming football freshman recruits to enter Penn State as special “presidential admits” who failed to meet the normal university admission standards. These athletes would play a significant role in Paterno’s first national championship in 1982 followed by another title four years later. Penn State football now appeared more focused upon winning rather than academic integrity. In addition, Paterno resisted any oversight of his players, who increasingly were subject to school disciplinary actions. For example, the coach challenged the right of Vicky Triponey, vice president for student affairs, to exercise any control over football players accused of violating school rules, and she resigned her position. Anwar Phillips, an outstanding defensive back, was allowed to participate in a bowl game on January 1, 2003 after the athlete was expelled from school after he was charged with felony sexual assault at a campus apartment. Paterno’s willingness to defy university oversight was evident in his support for women’s basketball coach Rene Portland, whom he hired during his brief tenure as athletic director. As Smith documents, Portland actively discriminated against players, contrary to university policy, whom she believed to be lesbians.

The most egregious example of Penn State’s failure to exercise control over its athletic program was the Jerry Sandusky scandal. Smith points out that allegations about Sandusky’s sexual misconduct with boys in his Second Mile charity were brought to the attention of Paterno and Penn State officials in both 1998 and 2001. And recently released testimony, unavailable when Smith’s book went to print, suggests that Paterno may have turned a deaf ear to allegations of sexual misconduct by Sandusky as early as 1976. The key question is why Penn State administrators such as Paterno, Vice President Gary Schultz, Athletic Director Tim Curley, and President Graham Spanier not respond to these earlier accusations before another round of allegations against Sandusky culminated in the convening of a grand jury and criminal proceedings. Smith concludes that the answer to this question is that key administrators, lacking any institutional oversight of the athletic department, assumed that maintaining the reputation of the Penn State football program was more important than the fate of Sandusky’s victims. As Smith notes, the continuing financial relationship maintained by the Board of Trustees and Sandusky’s foundation provides further evidence of a lack of compassion for the victims.

Smith’s criticisms, however, are not limited to Paterno, Penn State administrators, and the Board of Trustees. He notes that Pennsylvania Attorney General Tom Corbett was reluctant to fully pursue the investigation until after his successful campaign for the governorship of Pennsylvania. Smith is also critical of the investigation commissioned by the Board of Trustees and conducted by former FBI Director Louis Freeh. Smith argues that the Freeh Report often ignored due process and was overly broad in its indictment of the Penn State campus. He also censures the NCAA for its consent decree that essentially relied upon the Freeh Report rather than its own investigation. Smith believes that the NCAA had no business threatening the Penn State football program with a death penalty or imposing its draconian penalties upon the school. The Sandusky scandal was fundamentally a criminal case. It wasn’t a case of a team violating recruiting standards, which the intercollegiate association was created to oversee. While Smith is quite critical of Paterno and Penn State administrators, who placed the football program out of university oversight, he is also a proud member of the Penn State community. He concludes, “The evils, when attended to, may vanish, and Happy Valley will be left with hope” (183). Smith still believes in the dream of the “grand experiment” in which it is possible to blend academic and athletic excellent, but the stories of Joe Paterno, Jerry Sandusky, and Penn State University indicate how difficult this task is when college football generates billions of dollars in revenue.