Are We Raising Our Children Wrong?

November of 2015, I stood with a physician friend, gazing across the valley from the slopes below Italy’s Abbey of Monte Casino to the row upon row of white crosses on the mountainside opposite, where lay most of the Polish Division of the British army. In World War II, they had led off the infantry assault on the German positions above us. My friend grew up in India, old enough to understand the underside of the British Raj. I commented that I hadn’t known the Polish drew the short straw. My friend smiled sadly. Pretending to be a British general, he pointed to the Abbey above us. “There’s the Germans,” he said. “You Poles, you go first.” And the Poles had, responding with an internalized ethic of discipline and sacrifice. If they could not free their homeland, then they might die liberating Italy. That night, we listened to members of our group carp that you couldn’t get a good hamburger in Italy or that our rather nice hotel still put on the beds blankets that others had used. (Elite bedroom maintenance is apparently all about duvets with fresh covers.) “First World problems,” murmured my friend.

Months

later, July 3, 2016, I spoke at Gettysburg. We invited our two

oldest grandchildren to accompany us and their parents tagged along.

They hope their kids will stay immersed in books, educational

vacations, and athletics, avoiding the real dangers of teen life.

Yet it is not the older grandchildren I worry about most; I think

they will avoid the major pitfalls. No, I tremble for the younger

ones, who seem increasingly to require and receive a constant stream

of false necessities: treats, custom meals, and apps. One will only

eat spaghetti and meatballs canned by the right brand, another pizza

from the correct parlor with the essential toppings, etc. If this

trend continues, what will these little ones aspire to later in life,

beyond more and more consumer satisfactions? Will they have the

moral fiber to sustain the blows that life will inevitably deliver?

Months

later, July 3, 2016, I spoke at Gettysburg. We invited our two

oldest grandchildren to accompany us and their parents tagged along.

They hope their kids will stay immersed in books, educational

vacations, and athletics, avoiding the real dangers of teen life.

Yet it is not the older grandchildren I worry about most; I think

they will avoid the major pitfalls. No, I tremble for the younger

ones, who seem increasingly to require and receive a constant stream

of false necessities: treats, custom meals, and apps. One will only

eat spaghetti and meatballs canned by the right brand, another pizza

from the correct parlor with the essential toppings, etc. If this

trend continues, what will these little ones aspire to later in life,

beyond more and more consumer satisfactions? Will they have the

moral fiber to sustain the blows that life will inevitably deliver?

I pondered these questions as I watched portions of TNT’s Gettysburg (1993) with the older grandchildren in preparation for walking the battlefield with them. An exchange between two of General George Pickett’s brigade commanders, as they wait for the assault on July 3, struck me as particularly in strong contrast to the trends I see developing in our culture. General Lewis Armistead tries to dissuade General Richard Garnett from making the attack on Cemetery Ridge, as he can’t walk and riding will be a death sentence. Garnett responds that he must make the charge, ending, “Well, Lo. I’ll see you at the top.” It is that same spirit of duty and sacrifice that we see in Glory (1989) where Colonel Robert Gould Shaw feels impelled, at about the same date as Gettysburg, to lead his brave black regiment in a suicide assault on Fort Wagner in Charleston harbor. “I’ll see you in the fort,” he tells his old friend, Thomas.

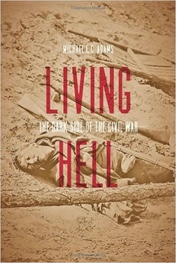

I think of those earlier Americans as I shovel heaps of child-rejected food into the disposal, wondering where we might have gone wrong. I’m not endorsing blood-letting as a cure for society’s ills. Europeans advocated that prescription in the early twentieth century and we know what that led to. But I do wonder if we in the comfortable classes have lost a sense of proportionality. Part of the aim of my book, Living Hell, is to show the terrible misery and suffering of the Civil War. But it also acknowledges the grit, determination, courage and devotion to public principle that inspired many. Yes, there were thousands of deserters, and many broke down, physically or mentally. There were war crimes and excesses committed. But many simply did what they had to do amidst horrors that today are almost unimaginable.

Today, one presidential candidate calls for America to be great again, but what is our role? Like a latter-day El Duce, is it all down to the strong-man leader? The other aspirant to the White House reasserts American exceptionalism, yet in what – the size of our restaurant portions? A relatively small percentage of the population finds fulfillment in military service. But soldiering is not for everyone. The psychologist William James witnessed two brothers ruined mentally and physically by the Civil War. Nevertheless, he saw redeeming value in the ethic of service. He called for a moral equivalent to war, which President John F. Kennedy parlayed into the Peace Corps. It is a good idea, but openings are limited and entrance requirements are stringent. Would not a generalized year of public service after high school bring back that sense of proportionality that our youth have lost, instilling a life-long ethic of concern for the common good? And perhaps many of us who are retired or semi-retired might show we still have a value to society, acting as unpaid guides and mentors to those who represent our future in many fields.

I have wondered throughout my adult life what it is that draws so many of us back to those four pivotal years of the Civil War, beyond the obvious issues of saving the Union or local rights, preserving freedom no matter how you defined it, or ending slavery. Increasingly, I feel that the re-enactors and buffs are not wrong; what they reach back for is something that really matters; it is character, and it is this that, most importantly, they try to convey to their audiences. Fair enough, dressing up on the weekends cannot allow you to fully regain the experience of the 1860s. But no matter how we do it, trying to connect with those who went through so much blood and muck for so much refreshes our sense of values beyond the frivolous and shallow.

As I see with satisfaction my grandchildren on Cemetery Ridge engaging with a re-enactor that I have buttonholed to chat with them, I think to myself, “Well, Lo. I’ll see you at the top.” I’m personally glad that the Confederacy lost. But the example of sacrifice given by those who marched out on the third day of Gettysburg, or followed young Colonel Shaw along Charleston’s beach, or indeed fell opposing fascism in Italy, should not be lost to us if we are not to succumb to the shallowness of First World problems.