Snowden: To Kill or Not to Kill

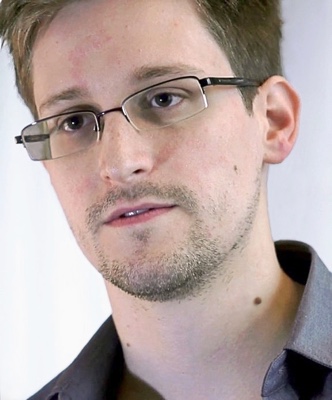

Edward Snowden - By Laura Poitras / Praxis Films, CC BY 3.0

While Amnesty International and the ACLU are pressuring President Obama to pardon Edward Snowden, Donald Trump has called for Snowden’s execution.

In June 2013, soon after the British Guardian and the Washington Post published the first stories based on Snowden’s files, Trump railed against the leaker of classified NSA documents on the Fox & Friends television show. “In the old days spies used to be executed,” he told viewers. “This guy is a bad guy. You know—there is still a thing called execution.”

To date, Trump has

never flip-flopped on his get-Snowden invective.

To date, Trump has

never flip-flopped on his get-Snowden invective.

Even if you disagree with Trump’s clarion-call to execute first and ask questions later, you have to admit that he dared to raise a politically incorrect question that resonates with Snowden’s enemies inside and outside the government: Why doesn’t a U.S. military-intelligence assassin silence Snowden once and for all?

Snowden wouldn’t be surprised if an Obama-approved assassin found a creative way to kill him in Moscow and blame it on Vladimir Putin. “You can’t come up against the world’s most powerful intelligence agencies and not accept the risk,” he told the Guardian. “If they want to get you, over time they will.” Snowden knows that even if he isn’t killed in Moscow, he would be in imminent danger if he leaves Russia.

The United States has a long and passionate love affair with assassins who carry out their missions within a legal fog. In l951, the U.S. military and the CIA jointly began to recruit and train a “guerilla corps” of Eastern European refugees, approved by President Eisenhower. (The guerilla corps is documented in my book, Useful Enemies: America’s Open-Door Policy for Nazi War Criminals.)

According to a l951 top-secret report of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), the guerilla corps would become the “organizers, fomenters, and operational nuclei of guerilla units…The primary interest in guerilla warfare during peacetime should be that of the Central Intelligence Agency and during wartime…the National Military Establishment.”

The JCS assigned specific tasks to the CIA guerilla units who knew the geography of countries behind the Iron Curtain and spoke their languages. Their mission was to rescue VIP fugitives and defectors, kidnap high-ranking communists, sabotage industries and communications, train and lead indigenous armies of freedom fighters, and assassinate double agents and communist political leaders. The JCS did not, however, address the legality of assassinations during peacetime.

The CIA deployed its hit squads from U.S. air bases around the world. According to one high-level military officer, quoted by author Christopher Simpson: “Some of these guys were the best commercial hit men you have ever heard of.”

No one knows how many communist leaders, double agents, and foreigners who posed a threat to U.S. security were assassinated by the CIA. We do know, however, that the leaders of communist or communist-leaning countries were at the top of the hit list. Among others: Patrice Lumumba (Congo), Rafael Trujillo (Dominican Republic), Ngo Diem (Vietnam); and General René Schneider (Chile). There was also a plan, approved by President Eisenhower, to assassinate Cuban President Fidel Castro.

The CIA carried out covert assassinations undetected for nearly twenty-five years, until a string of political earthquakes unearthed the practice. The first was the l973 Watergate hearings which parted the curtain on CIA covert operations. Watergate segued into the l975 Church Committee hearings in the Senate and the parallel Pike hearings in the House. They were mandated by Congress to investigate illegal snooping by the FBI and the NSA, as well as assassinations by the CIA.

At the recommendation of the Church Committee, President Ford reluctantly issued Executive Order (EO) 11905 in l976. For the first time, that order banned direct political assassinations. But it inadvertently—or deliberately—failed to ban indirect assassinations, whereby the CIA could hire foreign operatives to kill the agency’s political targets.

Six years later, in l981, President Reagan signed EO 12333. That order not only reaffirmed Ford’s ban on direct assassinations, it also closed the Ford loophole. “No agency of the Intelligence Community,” Reagan ordered, “shall participate in or request any person to undertake activities forbidden by this order.”

And yet both Ford and Reagan left the military-intelligence complex plenty of wiggle room. They failed to define the word “assassination”; or to distinguish between peacetime and wartime targeted killings as Eisenhower had; or to rule on the legality of assassinating an American citizen who is aiding the enemy on foreign soil.

On September 14, 2001, three days after the Al-Qaeda attack on the United States, Congress authorized President Bush to “use all necessary and appropriate force … to prevent future acts of international terrorism.” In response, Bush declared a War on Terror and made the assassination of terrorists a military mission. He left it up to President Obama, however, to determine whether it was constitutional to assassinate in a foreign country an American citizen who was aiding a terrorist organization such as Al-Qaeda or Isis.

In 2010, Obama set a new assassination precedent when he authorized the CIA to kill the radical Muslin cleric Anwar al-Awlaki. A U.S. citizen born in New Mexico, al-Awlaki was linked to an attempt to blow up a Detroit-bound airliner. The CIA traced him to Yemen and sent a drone to visit him.

If Obama issued an order to kill al-Awaki, did he also order the assassination of Edward Snowden? If not, why not?

Given that Americans are almost equally divided over whether Snowden is a traitor or a hero, to kill him would be a polarizing public-relations nightmare. And to assassinate Snowden in a foreign country that was protecting him would create a diplomatic crisis. Furthermore, Obama would need probable cause to order Snowden’s legal killing. And there’s the rub.

The Justice Department has charged Edward Snowden with three criminal infractions of the Espionage Act of 1917, which was enacted by Congress to protect the United States from communists and anarchists. The charges against him are stealing, possessing, and giving secret documents to unauthorized persons. If found guilty of those charges, Snowden could face up to thirty years in prison.

To date, the Justice Department has not charged Snowden with treason. The Espionage Act defines treason as taking, keeping, and/or transferring knowledge “with intent, or reason to believe, that the information is to be used to injure the United States, or to the advantage of any foreign nation.” If found guilty of treason under the Act, Snowden could face either life imprisonment or the death penalty.

For the Justice Department to charge Snowden with treason, it would have to marshal specific instances proving that Snowden materially aided the enemy. Handwringing and rantings aside, U.S. prosecutors, politicians, and members of the military-intelligence complex have produced no specific and credible evidence that Snowden committed such treasonable acts. They merely claim he has, and then quickly add that the information is classified.

Snowden’s greatest threat to the U.S. military-intelligence complex is not that he can continue to weaken national security. It’s that he might inspire more “Snowdens” to step out of the shadows of secrecy into the sunlight and … blow the whistle.