Review of Elizabeth Hinton's "From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime"

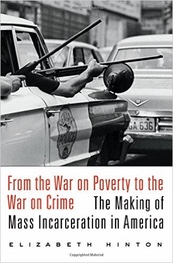

I must confess that my first thought on being asked to review yet another book about “mass incarceration” was jaded disinterest: There can’t possible be anything more to say about this topic. I was wrong. It turns out there’s a lot more to be said, and Elizabeth Hinton's From The War on Poverty to The War on Crime (Harvard University Press, 2016) says it thoughtfully, passionately, and clearly. The conventional wisdom about the “punitive turn” in the United States locates its origins in the rise of free market economic policies and the political shift to the right, emerging first under Nixon, consolidated by Ronald Reagan, and then fully embraced by the Clinton administration. There is a tendency in this viewpoint to characterize the post-World War II period in binary terms: liberals versus conservatives, social democracy versus neo-liberalism. Hinton, an Assistant Professor of History and African and African American Studies at Harvard, takes issue with this interpretation, arguing that the modern carceral state has deep and wide political roots, and owes as much to the liberal social-democratic tradition as it does to the rise of the New Right and Neo-Cons. She adds an important chapter to the revisionist tradition in American historiography: from Gabriel Kolko’s analysis of the repressive underside of social democracy in the Progressive Era (The Triumph of Conservatism, 1967) to Naomi Murakawa’s insight about the role of “liberal law and order” in the Truman administration (The First Civil Right, 2014).

I must confess that my first thought on being asked to review yet another book about “mass incarceration” was jaded disinterest: There can’t possible be anything more to say about this topic. I was wrong. It turns out there’s a lot more to be said, and Elizabeth Hinton's From The War on Poverty to The War on Crime (Harvard University Press, 2016) says it thoughtfully, passionately, and clearly. The conventional wisdom about the “punitive turn” in the United States locates its origins in the rise of free market economic policies and the political shift to the right, emerging first under Nixon, consolidated by Ronald Reagan, and then fully embraced by the Clinton administration. There is a tendency in this viewpoint to characterize the post-World War II period in binary terms: liberals versus conservatives, social democracy versus neo-liberalism. Hinton, an Assistant Professor of History and African and African American Studies at Harvard, takes issue with this interpretation, arguing that the modern carceral state has deep and wide political roots, and owes as much to the liberal social-democratic tradition as it does to the rise of the New Right and Neo-Cons. She adds an important chapter to the revisionist tradition in American historiography: from Gabriel Kolko’s analysis of the repressive underside of social democracy in the Progressive Era (The Triumph of Conservatism, 1967) to Naomi Murakawa’s insight about the role of “liberal law and order” in the Truman administration (The First Civil Right, 2014).

Delving into government documents, policy statements, and legislative debates, Hinton’s focus is on the politics of urban governance from Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty through Reagan’s War on Drugs. This approach can easily get mired in empirical details, but her smart analytical narrative and choice use of source material make for a lively read.

Hinton demonstrates that from the beginning the Kennedy-Johnson War on Poverty was a battleground of ideas and policies between mostly grassroots struggles to extend the benefits of the New Deal to communities of color, and top-down efforts to construct the foundations of the urban carceral state. For a very brief moment, the civil rights, black liberation, and feminist movements, in alliance with liberals in government, created the possibility that the United States would follow the social democratic path forged by most countries in the West, with guarantees of income, health, education, and equal access to public services.

The 1964 Economic Opportunity Act planted the seeds of equal opportunity and community empowerment. But, says Hinton, the Johnson administration also planted the seeds of repression. The book’s title notwithstanding, the War on Crime was a central component of the War on Poverty, with “statistical discourses of black criminality and pathological understandings of poverty serving as its intellectual foundation.”

Hinton leaves no doubt that racism was at the core of the new urban carceralism, a fierce pushback against rebellions in Watts and other cities that resulted in the arrest of tens of thousands of African Americans and new strategies of social control, from velvet glove techniques of cooptation and management, to an iron fist of counter-insurgency operations tested in Viet Nam. She digs up some telling examples: Nixon’s aside to his chief of staff in 1969 that “the whole problem is really the blacks…. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to”; Reagan’s statement to the International Association of Chiefs of Police in 1981 that “only our deep moral values and strong institutions can hold back that jungle and restrain the darker impulses of human nature.”

Yet, Hinton does not regard contemporary racism as simply the leftover debris of the segregated past or as an echo of slavery. She makes the important point that “the long mobilization of the War on Crime was not a return to an old racial caste system in a new guise – a ‘New Jim Crow’. Rather, the effort to control and contain troublesome groups with patrol, surveillance, and penal strategies produced a new and historically distinct phenomenon in the post civil-rights era: the criminalization of urban social programs.”

We follow the book’s main argument about the interweaving of repressive and progressive policies in urban social programs as they were articulated and implemented by successive administrations, with an emphasis on the expansion and refinement of carceral strategies: Johnson’s investment in urban policing, backed up by corporate and military assumptions about the War on Crime; Nixon’s use of discretionary funds and executive powers to grow the penal system, and enlist academics in devising new methods of punitive control; Ford’s emphasis on special programs for “violent repeat offenders” and “career criminals”; Carter’s efforts to extend the carceral state to public housing projects in the guise of “urban revitalization initiatives”; and Reagan’s acceleration of mass imprisonment, and contracting out of penal operations to the private sector.

By the time that Clinton became president in 1993, says Hinton, both parties shared a “deep commitment to crime control as a viable response to socioeconomic inequality and institutional racism.” Whether it was Los Angeles’ rightwing police chief in 1965 comparing the black residents of Watts to the Viet Cong, or Democratic Senator Joe Biden in 1982 describing crime as “a national defense problem” that put us “in as much jeopardy in the streets as you are from a Soviet missile,” the militarization of urban criminal justice operations enjoyed “a broad bipartisan political consensus.”

After a compelling analysis of the repressive strain that runs through post-World War II, American liberalism, Hinton tries to provide a glimmer of hope in her conclusion by discussing what it will take to move toward “a more equitable and just nation.” She wants us to imagine “what the United States might look like today” had policymakers “steered the War on Poverty’s community action programs with the same level and length of commitment as they gave to the War on Crime.”

Unfortunately, the mostly top-down, retrospective account of the 1960s does not make this alternative path seem like a credible choice, either then or now. Hinton wants to resurrect “the principles of community representation and grassroots empowerment” embedded in the progressive ideas of the “Great Society,” but does not address how this might be achieved in the current political climate, whether Trump’s defense of the thin blue line or Clinton’s centrist reforms. So, unlike the rest of this relentlessly unsentimental, compellingly argued book, the last few pages have a whiff of nostalgia.

Elizabeth Hinton, however, is not alone in struggling to articulate a progressive vision that speaks to the current interregnum, when the old regime is crumbling and the new one has not yet emerged, when, as Antonio Gramsci put it, a “great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” Recent protests on the streets and in prisons suggest that social activism and organized opposition can have a far-ranging impact on carceral institutions that always bend to the arc of power, but are vulnerable to struggles from below. How to build protests into a serious movement while staying alert to the carceral underside of liberal reformism is the challenge we face. In this context, Hinton’s cautionary tale is a must read for activists.

* To be published in Punishment and Society(2017).