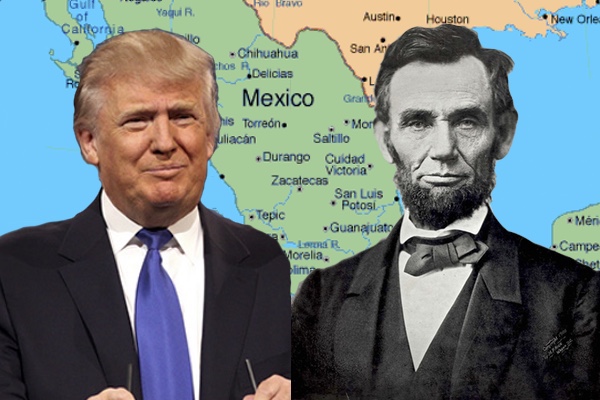

Next Time Trump Bashes Mexico, Remember This

For many people it is hard to imagine a time when Mexico was a place of pilgrimage for an American president who went there to both apologize for the US treatment of that country in the past, but also to initiate a Good Neighbor Policy that would affirm his belief that the destinies of the two nations were intertwined. But when Harry Truman laid a wreath at the Mexico City memorial of the Niños Heroes, or Boy Heroes of the US-Mexican War, he was following in the footsteps of another president, Abraham Lincoln, who stood up as a Congressman in Illinois to protest the “unnecessary and unconstitutional” invasion of that country at the orders of James K. Polk. He accused Polk of lying and of creating a pretext for the preemptory invasion. As a result of that war, the US acquired two-fifths of Mexican territory including the states of California, Utah, Arizona and Nevada, as well as parts of present-day Kansas, New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming.

When

Lincoln stood up in Congress to protest, he pointed out that the

pretext Polk used to declare war (“American blood was shed on

American soil!”) was a lie and set about to prove it with a series

of “spot resolutions.” These essentially consisted of eight

examples which challenged the president to show the exact spot where

the alleged blood was shed. Lincoln proved conclusively that it was

on Mexican soil, and that the Americans were the invaders.

When

Lincoln stood up in Congress to protest, he pointed out that the

pretext Polk used to declare war (“American blood was shed on

American soil!”) was a lie and set about to prove it with a series

of “spot resolutions.” These essentially consisted of eight

examples which challenged the president to show the exact spot where

the alleged blood was shed. Lincoln proved conclusively that it was

on Mexican soil, and that the Americans were the invaders.

As a result of Lincoln’s courageous stance in Congress, he was castigated in the press, called “spotty Lincoln” by his critics, and abandoned by his party and by his supporters. He was accused of giving aid and comfort to the enemy. He lost an election to the Senate and was even turned down for an appointment as postmaster. It seemed like his political career was over. Although many US historians have advanced the theory that Lincoln spoke against the war for political reasons, his subsequent speeches disprove that theory as do his letters to his law partner, William Herndon. He railed against the war a second time a month after his famous “spot resolutions” over objections of the younger members of his party, and even voted for an amendment condemning the war which was tacked on to a resolution honoring war hero Zachary Taylor, who would become the next president.

When Lincoln finally became president himself as a compromise candidate, one would think he had enough on his plate with the South about to succeed and with a fratricidal war on the horizon. Yet he made time even then to meet with the Mexican Ambassador Matías Romero, who visited him at his home in Springfield shortly after the election. Lincoln wrote Romero a letter reassuring him and the new president of Mexico, Benito Juárez, of his support of the Mexican people and their republic.

By 1863 the US was fully engaged in the Civil War: the Battle of Gettysburg was in full swing, and France had invaded Mexico and set up the puppet emperor, Maximilian. As both Austrian and French troops occupied Mexico, Lincoln—careful not to burn bridges with France lest they unite with the Confederacy—soft-pedaled his aid to the Mexican government in exile. He had his advisers confer secretly with Romero (now without credentials since President Juárez was in El Paso), and even met with him personally on several occasions. Mary Todd Lincoln and Romero went on shopping trips together and had intimate conversations. Romero used the Lincoln letter of friendship to approach banks in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and San Francisco to solicit investors to buy a Mexican bond issue. He was able to raise over $18 million.

As the war came to an end in the east, he was able to circumvent Secretary of State Henry Seward’s cautious approach and help persuade Lincoln to order General Grant to move over 50,000 troops under the command of General Sheridan to the Texas border, including thousands of “colored troops” (as the African-American soldiers were known at the time). The goal was to help Mexicans at the end of the US Civil War to drive out the French. Sheridan purposely “lost” 30,000 repeating rifles on the border where the Juárez army could find them. Although Lincoln would be assassinated shortly after the surrender of Appomattox, his generals continued to help Mexico. They encouraged the recently-discharged troops to form the American Legion of Honor which would fight side by side with the Mexicans, helping rid the country of the last remnants of European occupation.

In 1947, Harry Truman, a Democrat, came to Mexico to reaffirm what a Republican president, Abraham Lincoln, had affirmed throughout his career: the Mexican people are not only our neighbors but the entire southwestern US was formerly their territory. Mexico and the US share today a vast territory in North America and neither side can afford animosity or discord. Americans were the first illegal immigrants to their country, violating their laws, fomenting revolt, and later with our army violating their sovereign territory. It is well to remember that when we are tempted to react with frustration or impatience.

Our later history under Lincoln made us allies, helping to rid Mexico (and us) of an unwelcomed foreign power in this hemisphere. As an American historian, living and teaching in Mexico, it is my hope that this re-visioning of our mutual histories in Abraham Lincoln and Mexico might quiet the polemics raging in the US since the recent election, and let us hear the quieter voices which speak to us from the past about how we might be “good neighbors” once again.