The Myth About Obama’s Red Line in Syria

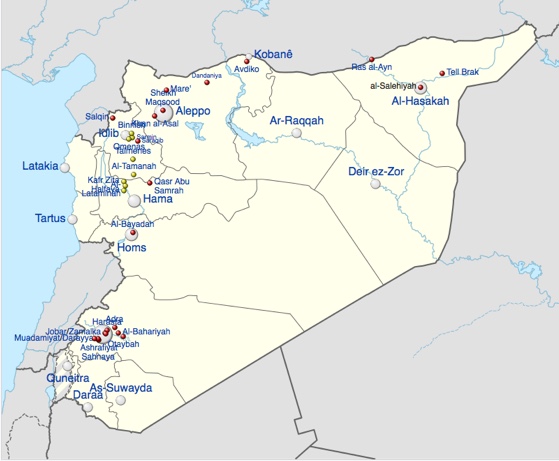

The map marks the position of reported chemical weapons attacks in the Syrian Civil War. Yellow markers indicate chlorine attacks. Red indicate a more deadly chemical weapon agent.

The great undoing has started. President Obama’s most defining achievements – from healthcare reform and economic recovery to the drawdown of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan – divided the country to the extent that our new President and Congress are hell bent on undoing anything that might be considered an enduring legacy.

Of the many arenas for expected change, perhaps the most consequential will be the departure from Obama’s approach to advancing and protecting U.S. interests in the world. Obama consistently prioritized diplomacy. His two major international accomplishments came through diplomacy: securing an agreement to prevent Iran’s development of nuclear weapons and the international climate change agreement. Unfortunately, both are high on the list of the great undoing of the Trump administration, regardless of the possible costs.

Donald Trump and his team cite a presumed loss of international prestige and influence around the world as a result of Obama’s reluctance to use military force without exhausting diplomatic solutions. As their case in point, they have advanced a narrative about the no-good options case in a prolonged Syrian civil war. Such a narrative has taken on a conventional wisdom that ignores the events that actually transpired.

The narrative has its own short-hand nomenclature: the red line. In Syria, Obama laid down a “red line” in August 2012 that, once crossed by Syria’s President Bashar Assad, would draw the U.S. into military engagement in Syria. Obama’s exact words were “a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized. That would change my calculus,” referring to a decision on military involvement in Syria.

Within a year, video footage out of Syria began to seep out of Syria forcing such a “change of calculus.” An August 21, 2013 attack against a suburb of Assad’s own capital revealed use of chemical weapons, and UN inspectors arrived in Syria to investigate. Obama began preparing the groundwork for a military response, first by consulting with allies and then exploring options of limited strikes to cripple Assad’s ability to use chemical weapons. Planners assessed the risks of military strikes against caches of chemical weapons. While the U.S. had a stated policy of regime change in Syria, Obama focused his planning for military option on one achievable goal – the removal of chemical weapons.

A timeline of events over the next few weeks reveals how quickly events on the ground shifted to disrupt Obama’s plans.

On August 29, the British Parliament voted against Prime Minister David Cameron’s motion condemning Assad for the attack, the first step for British participation in military intervention. Weighing heavily on that vote was the still fresh memory of the consequences of British involvement in the Iraq war.

Faced with the loss of his closest ally, Obama made two announcements two days later. First was his decision to “take military action against Syrian regime targets.” The second was more consequential. He also decided to “seek authorization for the use of force from the American people's representatives in Congress.”

At the time, Obama sounded confident that he would be able to convince Congress on the appropriateness of military action, despite his awareness of the public’s weariness with war after Iraq and Afghanistan.

After just one week, it had become clear that Congress would not back Obama’s request to use military force in Syria. Public opinion polls also opposed U.S intervention, and Obama was running into the same brick wall that a Republican Congress imposed on any proposals emanating from the White House. On September 8, five Republican Senators announced their opposition and a sixth, Lindsey Graham, said “It'd be great if the Russians could convince Assad to turn over his chemical weapons to the international community. That'd be a terrific outcome.”

Faced with a near certain defeat in Congress, Obama’s room to maneuver was limited. In what has been portrayed as an off-the-cuff remark, Secretary of State John Kerry opened up a potential avenue to achieve the same outcome as a military strike of eliminating the chemical weapons that Assad could use on his own people. In response to a reporter’s question on September 9, Kerry said Assad could avert military action by the U.S. if he would “turn over every single bit of his chemical weapons to the international community in the next week.” The Russians moved quickly to propose just such an outcome. Obama responded tentatively, holding out the use of military action if such a plan was merely cause for delay.

The next day, Obama asked Congress to postpone a vote to allow for diplomacy to play out the diplomacy set in motion by Kerry’s remarks.

After an intense, accelerated negotiations, Kerry and his Russian counterpart announced on September 14 the framework of an agreement that would start a process to remove the chemical weapons in Syria under the supervision of the international community.

Less than a year later, on June 23, 2014, the UN certified that the last of Syria’s chemical weapons had been removed. That included over 1300 metric tons at over 45 different sites in Syria. The size alone of that stockpile makes it hard to conceive that military intervention would have had the same outcome.

Obama’s detractors, especially those in Congress who worked to thwart approval of military engagement in Syria in September 2013, suffer from amnesia. Not content with this erroneous story line, some have connected the red line statement to the continued suffering in Syria, to the military involvement of Russia to bolster Assad, to a mass migration to escape what looks to be genocide in Aleppo and Syria’s other war-torn regions. This is misplaced; Assad and Putin hold full responsibility for those crimes against humanity.

The red line narrative that ought to be taking hold as the nation prepares for the transfer of power reveals a leader who laid out a concrete goal and achieved it, through diplomacy that involved the UN, friends and allies, and even adversaries. We will come to appreciate such strategic deliberation. My thread of hope is that we as a nation do not pay too high a price for the untethered, transactional bullying that lies ahead.