For Whom the Bell Tolls? It Tolls for Us.

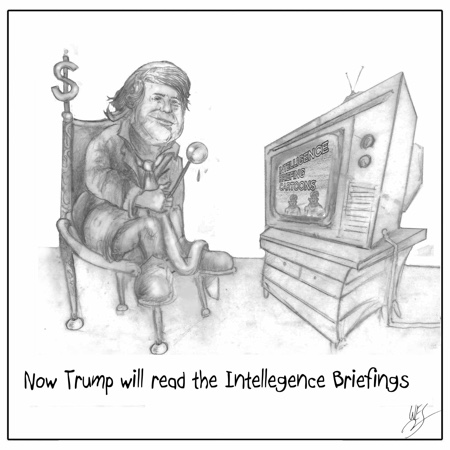

Illustration by Wes Jenkins

Several of you have performed a major public service in focusing your readers’ minds on the dilemmas posed by the Trump administration. I suggest that you push the issue harder and in more defined categories.

Here I will suggest what

seem to me to be the major categories of challenges men who care

about the country face, but before I do, let me frankly state my

position: I think the Democratic Party leaders had it coming to

them. Obama’s rhetoric raised hopes but then he did far too little

to meet the expectations. Those of us who had lived in the same

environment in Chicago foresaw his passivity in the White House; it

was already evident in community meetings. He was never a determined

advocate. From his first foray into politics, he concentrated on

image rather than action. However, I voted for him both because the

other choice was unattractive and because by simply being elected he

was pushing the agenda of American freedom. Thereafter, I think

almost everyone was disappointed. Several of your respondents have

detailed the record so I will skip it here. Then came Hillary. Even

those of us who favor equality for women found it hard to stomach her

activities. The only thing many found compelling about supporting

her was that she was not Trump. Had the Democrats put forward an

attractive candidate we would not today have Trump.

Here I will suggest what

seem to me to be the major categories of challenges men who care

about the country face, but before I do, let me frankly state my

position: I think the Democratic Party leaders had it coming to

them. Obama’s rhetoric raised hopes but then he did far too little

to meet the expectations. Those of us who had lived in the same

environment in Chicago foresaw his passivity in the White House; it

was already evident in community meetings. He was never a determined

advocate. From his first foray into politics, he concentrated on

image rather than action. However, I voted for him both because the

other choice was unattractive and because by simply being elected he

was pushing the agenda of American freedom. Thereafter, I think

almost everyone was disappointed. Several of your respondents have

detailed the record so I will skip it here. Then came Hillary. Even

those of us who favor equality for women found it hard to stomach her

activities. The only thing many found compelling about supporting

her was that she was not Trump. Had the Democrats put forward an

attractive candidate we would not today have Trump.

A “Trump” is always on offer in every political system. As James Madison telling wrote in his essay, Federalist X, “Men of factious tempers, of local prejudices or of sinister designs, may, by intrigue, by corruption, or by other means first obtain the suffrages, and then betray the interests, of the people.” American history records a number of them. Just take two: In recent times, Richard Nixon sought to prolong the Vietnam war in order to win the presidency, Ronald Reagan or his team sought to delay the release of hostages in Iran similarly in order to win his election. The threat of war is nearly always a sure winner in elections. The film Wag the Dog is closer to being a documentary than we would like.

So here we are. What is important now, I think, is to develop a clear strategy to employ in the coming four years. But, I find that most of us are thinking with our hearts instead of our heads and/or confusing our annoyance at what Trump is doing with what we need to do to right the Ship of State. Annoyance is satisfying but ultimately insufficient.

So what needs to be done? Here I suggest are some of the categories for action in the coming four years. We must not just pout. We must think with our heads and get together and reform not Trump, who is probably not capable of being reformed, but ourselves and reassert our institutions and our fundamental credo.

First, it seems to me that what the ACLU, some judges and some of the states are doing is a necessary first step. Where actions exceed the law, they must be stopped. We cannot allow a slide into actions or positions that will be difficult, once set up, to dismantle or reverse. But, however necessary, such moves are insufficient. They must be carried on vigorously but they must not make us relax in the belief that judges or other citizens will do the job for us. As Harry Truman famously said of his role, “the buck stops here.” It stops with us. Or as John Donne more poetically put it, “send not to know, For whom the bell tolls, It tolls for thee.” It tolls for us. Nor are restraints sufficient; we need to take affirmative action on our institutional arrangements. Having been taught again, as the Founding Fathers tried to teach us, their weaknesses, we must protect them.

Second, we must find ways to reemploy neglected or atrophied institutions and engage new centers of influence. Like many people who have studied other political cultures, I have been repeatedly struck by the inherent flexibility and resilience that our complexity has given to American society. It begins with our ruling institutions. Deeply influenced by Montesquieu’s De l‘Espirit des Lois, the Founding Fathers sought to divide governmental power into three parts. As Montesquieu had warned (Book One, Part 6) “When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty…” That was the prime consideration of the men who wrote the Constitution. They realized that it might not work; what they were putting together some called “an experiment.” They expected that it would come under attack by ambitious and immoral men.

Today, President Trump appears, at least temporarily, to have gained control over two organs of government and perhaps will reconfigure the Supreme Court to abide by his decisions. If this amalgamation of power is allowed to continue, there appears reason to believe that, as Montesquieu continued, “the life and liberty of the subject [citizen] would be exposed to arbitrary control.”

This is the structural challenge we face today, but there is a deeper sense of agreement in which we can draw hope for a return to the divisions built into our Constitution. Over the generations since the Founding Fathers analyzed the American society and prescribed a formula under which we could live together, we have multiplied the separate activities and groups that form our society.

Individually, these groups and activities are often small, marginal or weak, but in the aggregate they weave social fabric of great strength. Even more to the point, one or other, sometimes several, of the various groups – churches, synagogues, mosques, labor unions, discussion clubs, professional societies and others --touch us all. We need to help them identify common causes. This is partly an external task – education, advocacy and example – but it is also in part a semi-automatic process that arises from perception of self-interest.

Let me give what might become a typical but so far unengaged example: the professional society of scholars of the Middle East, MESA. As a group, the 3,000 or so members are not very influential, and have never been politically active, but they are scattered across America and many take part in local committees on public and foreign affairs. They hold a yearly meeting in which younger scholars can demonstrate their work and seek job opportunities. This year, they find that current policies make it difficult to meet. If they meet in America, as they always have, some of the members may not be able to attend; if they meet abroad, some members may not be able to return. In protest, they considered postponing or canceling their meeting. Had they done so, it would have been a small gesture, but it might have been replicated by dozens of professional groups throughout the country and some of which have active public outreaches.

They decided to take more direct action: they joined with other disturbed groups to bring action in court to ask the Federal Court in Maryland to block the executive order banning entry for residents of seven Middle Eastern countries. This sort of action may be replicated by other groups in the coming months as each begins to see its interests imperiled by president decree.

Third, we need to review the structure of the electorate. The Trump revolution was made possible not only in the more visible (and vocal) pronouncements and edicts on which the media was (and still is) concentrating but. structurally at the state and local level. Gerrymandering of districts, to which the Democratic Party stalwarts seem to have been oblivious, virtually destroyed proportional representation in much of the country. The latest, as I write, come in Georgia where state authorities are so recasting election districts as to diminish representation of blacks. Dismantling the current layout will be a hard struggle, but unless districting is at least partly returned to the status quo ante there is little chance for better representation. The Democratic Party been treated to, and acquiesced in, what amounts to assisted suicide.

Fourth, the flow of money into politics. Institutionally, America has become a political market. We put the country up for rent every two years. Our paid employees, our representatives, spend a large part of their time, many spend almost all their time, importuning, soliciting or prostituting themselves. Some vote according to belief or conscience, but it is hard to escape the impression that the Congress as a whole is literally a whorehouse. Almost everyone’s vote – his “service” -- can be bought. Lobbyists for special interest groups have a clear-eyed view: they know the price of each member.

As long as this system is unchallenged it will result in such egregious legislation as that forcing agencies of the Executive to purchase goods and services at inflated prices or to buy more than they believe they need.

Much worse is the political effect. The members by and large do not represent those who sent them to Washington but those who hire them when they arrive. Those who benefit from the largess of special interests will have little incentive to reform, unless or until the public is mobilized to demand that the public weal be put into play.

Bringing about that transformation is partly a matter of education of the public. Some of the issues that must be ventilated are or should be simple to explain: would anyone knowingly hire a person who helps steal his money? Put that way, in simple terms, people might slowly come to understand that it is their money, their houses, their health, their jobs and their liberty that is being taken. It is notable that while Mr. Trump keeps emphasizing that he is making America great the budget he has laid out diminishes the well-being of the vast majority of Americans. Income of the lower and middle income groups has fallen and will fall further if his program is implemented while benefits to the upper 1% are increased. When the public, including his supporters, grasp that single fact, they might be, should be, motivated to demand a change of course. Achieving that understanding will require education in civic virtue as the Founding Fathers knew. So we had better get at it.

But, no matter how skillfully or how energetically we push for public interest criteria in public policy, we have seen that the public often closes its collective eyes. The public can be misled, manipulated or itself bought by special interests and propaganda. Astonishingly, there has been no effective demand that the “robber barons,” as our grandfathers called them, be punished for illegal and disastrous actions that caused many people to lose their houses and their jobs. The justice system rightly puts into jail a man who robs a store but none of those who virtually stole the country in financial scandals was even indicted.

As a young man, I thought this was only a sign of the degeneracy of our times. I thought that our elders and betters cared more for the country. I was set strait one night when I sat at dinner next to the oldest attorney then practicing before the Supreme Court . He was 90 and I was 40. I put my observation on current malfeasance before him. He laughed and said, “young man, when I was your age, no one would even have noticed.” The Robber Barons didn’t even bother to hide. From this and other evidence, I conclude that private greed and even private necessity is built into the system.

The system we have evolved is built on money. Even an honest, dedicated, civic minded legislator on the state or Federal level must, or believes he must, get the great amounts of money required to hire time on the media. If he does not, he believes that he is sure to lose the election to one who raises more.

Generally but not always the candidate is right. There is a high correlation of money spent and electoral victory. Are there limits? One aspect of the last election that may give a glimmer of hope is that, apparently, the public reacted against the Clinton campaign’s blatant commercialization. Perhaps that glimmer can be focused.

Indeed, others have focused it. Realizing the political trap the need for money sets, some countries, notably Canada, restrict the amount that can be spent on a campaign and others, notably England and France, limit the campaign span. Attempts have been made in America to address this issue, but they are small scale and have been thwarted by the Supreme Court.

A different approach was suggested in the discussion on the allotment of the airwaves which our fathers in the 1930s regarded as public property. Over the years, these grants have been staked out as private property. And the terms on which the grants were made have often lapsed or be denigrated. The networks that sell “our” air waves profit by selling what was originally understood to be a national trust. That may be reprehensible, but what is really important is that this usurpation has distorted the political process. Attempts to provide alternatives like NPR were never adequately funded and now are marked for extinction. This must be resisted. We need access to diverse opinion and sufficient information to be able to carry out our civic responsibilities. Probably little will be accomplished unless or until it becomes evident to the public that the current system is a dagger thrust into the body politic.

We now have a sort of shield in the web but at least so far emails cannot compete with television. However, the existence of this alternate source of communication gives us alternative sources of real-time information. More important, it could give an opportunity to stake out measures of reform of the major media. If we are to use that opportunity, we must begin to prepare for it by education. Doing so will be hard and difficult but there are useful precedents like the “Hutchins Commission on a Free and Responsible Press” that was created just after the Second World War. Still extant are beacons of light in this field like the Neiman Foundation, the Columbia School of Journalism and various associations of newsmen. They have small voices and will need help so again we must find them, listen to them and support them.

Fifth, business: President Dwight Eisenhower warned us against the Military-Industrial Complex – and we have added its call girl, Congress, to its ranks – but its ranks are not a phalanx. Even in Eisenhower’s tenure, the massive forces of the arms industry were hurled against one another. That was true because there was a limited amount of money to be divided. Each behemoth wanted it all. So as Eric Schlosser has pointed out in his study of the war business, Command and Control, “General Dynamics Corporation lobbied aggressively [for its product the missile] Atlas; the Martin Company, for Titan; Boeing for Minuteman; Douglas Aircraft for Thor; Chrysler, for Jupiter; and Lockheed, for Polaris…” As the Founding Fathers thought, in division lies safety. But then Eisenhower, growing weary, simply “agreed to fund all six.” That has already been announced to be the policy of the Trump administration. Increased expenditure for all arms including an extra $1 trillion to upgrade and make more “usable” nuclear weapons. Our best, perhaps our only, hope lies in fiscal restraint.

A policy of fiscal restraint on “defense” will be extremely difficult to effect. It may even be impossible. The Department of Defense itself does not even know where the money goes. Duplication, over-charging, non-performance and waste are on such a scale and so prevalent that they are hardly even noticed. No satisfactory audit has been performed for the last generation!

The arms industry, Eisenhower’s military-industrial complex, hardly needed to worry: it has not only bought the Congress directly but has also shrewdly anchored itself in each Congressional district. Companies working on government contracts have divided much of their procurement among communities so virtually every Congressional district is producing some piece of hardware. Congressmen reasonably heed the demand of local businessmen who want to make a profit and local workmen who want “quality” and long-lasting jobs.

In lush times, no one cares. And even when an administration robs Peter (public works and beneficial social programs) to pay Paul (“defense”) few voices are heard. Although bridges, dams, roads, schools and other public buildings are allowed to deteriorate, there is little public outcry. Indeed, the aim of the current administration is to stop what little was being done in the last administration. A few economists, some thinkers on public policy and even a large number of senior military officers have warned that this policy actually weakens America militarily and could lead to a severe social and economic crisis, but, to no avail. The Trump administration does not credit its critics and advisers and the public seems oblivious. The fact that America already spends more on “defense” than the next eight of the big spenders to no apparent avail is greeted by demands to spend even more. Sixteen years of war in Afghanistan, to take only one example, have killed a lot of people (both ours and “theirs”) but have brought neither peace nor security. The old saying hits only a part of the current policy failure – “throwing good money after bad.” Worse is evident: hatred of America has spread far from Afghanistan, more people are being killed in more places, and sense of hostility among Americans has grown with a perceptible decline in the belief in and functioning of American democracy. All signs point to a further accentuation of this trend.

Will anyone care? The stock market is booming. Unemployment has at least stabilized. Some economists predict a “correction.” But periodic down-turns affect mainly those who cannot defend themselves or who lack the means to recover rapidly. Even major set-backs like the 2008 financial crisis in which many people lost their houses and/or their jobs have not been effective wake-up calls. Few institutional or legal adjustments were made and the plight of the victims was soon forgotten, even, apparently to judge from the last election, by them. It may take a truly devastating set-back like the Great Depression to wake us up. Some warn that such an event may come, but probably not in the near-term. Meanwhile, the public slumbers.

Easier will be the task, I think, of convincing business leaders that the Trump “America First” policy is against their interests. It is a truism that we live in an interconnected world, at least economically. American business has long profited from cheap overseas labor. As I read on my cell phone, my computer, even my underwear, the phrase “made in…” rarely ends with the word “America.”

Although in my youth, “made in England” or wherever was a recommendation, some now see “made in China” as indicating the product should be set aside for a good American product. But how could we sell our goods if we did not buy from others. For many years, we operated on a principle of free trade. Thus if, as Mr. Trump proposes, we batten down the hatches of trade and buy “only American,” we will quickly lose markets and in doing so will lose job opportunities at home. Perhaps then both major corporations and skilled workers will begin to be willing to consider their real interests.

Sixth, underneath all these feelings about foreigners is a deeper dilemma: we are all immigrants but are divided by tenure. Some of us are very new; others descend from ancestors who “come over on the Mayflower.” That division is very important in American society. Crediting it has accentuated a very old and ugly aspect of the American experience. We all talk about e pluribus unum but while we asserted it on the “macro” level of institutions, or at least symbolically in parades, we never really practiced it ourselves on the social level. We have never been good at enjoyment of difference or even of tolerance among ourselves.

In the early days in America, New England towns were so distrustful of one another that a family would have to get permission to invite even relatives living in other towns to visit; when people were thrown together, as in traveling, they clung to those with whom they shared beliefs, language, origin and class. As one traveler described them at their most convivial, in taverns, little groups formed “parliaments” – groups that ‘spoke together,’ which is the original meaning of the word – apart from those who differed in any respect. It would never have occurred to Protestants to speak or sit with Catholics or Jews. Italians and Irish might be allowed into the tavern, but Blacks and Indians would have been shot at the door. Tolerance was not a familiar concept.

Throughout much of American history, we have generally at least until lately followed our colonial custom. We got rid of as many Indians as we could, we enslaved the blacks, segregated the Irish, Italians, Greeks and, of course such different looking and different dressing aliens as the Chinese. When in doubt, during World War II, we packed the Nisi off to camps. And we told everyone what my ancestors, the WASPs, thought of them by what we called them, Niggers, Wops, Greezers, Messakins, Chinks and Japs.

The odd thing was that not only did we push them away but that they pushed themselves away. But not only from us; they pushed away from their own cultural roots. Let me bear witness.

When I was a boy in Texas, I spent a year in a grammar school in the Mexican district of Fort Worth. I was practically the only gringo, but I do not recall having ever heard a word of Spanish spoken. Everyone in the school was ashamed of being Mexican. Much later, in college, I volunteered to teach young Italian-Americans in a Boston settlement house. When I read Pinocchio to them they could not believe that an Italian could write a book and when I took them to the Boston museum they were astonished to see Italian names under the great paintings. To them, Italian was the old grandmother with her hairy lip, ugly, backward, un-American. Even blacks tried desperately to “pass.” Millions did. The melting pot boiled away differences. And those who could rushed to jump in. It some ways, no doubt, this made for harmony, and it perhaps formed the basis for our belief in American exceptionalism, but it did not promote brotherly love.

Far from brotherly love, we failed, notably I believe, to develop a sense of shared interests. Individualism has remained a theme some of our ancestors brought with them from their homelands and others developed on the ever-expanding frontier or borrowed from those who homesteaded toward the west. Little groups it is true helped one another raise the roof beams and joined to chase away or kill the Indians, but when it came to national interests, General George Washington found that even in the midst of battle, the militia troops had a habit of running away, occasionally without even firing their weapons. Washington regarded them as cannon fodder. And, despite our pride in the Spirit of ’76, it is more evident in retrospect than it was then. As the chief engineer of the Continental Army, the French volunteer Louis Duportail, lamented, ”There is a hundred times more enthusiasm in any Paris cafe [for the American Revolution] than in all the colonies together.” Many kept focused on their private aims, sold food and equipment to the British and starved Washington at Valley Forge; others found it more profitable (and safer) to kill Indians than to fight the British.

This is not surprising: we see it today among the formerly colonial peoples of Africa and Asia. The growth of a national esprit de corps is a very slow process and as it develops it experiences many set-backs. We see them glaringly in shaky regimes and “failed states.” Often the newly liberated people come to feel nostalgia for the former regime. The former colonial auxiliaries become oppressive armies and the former freedom fighters often become corrupt tyrants. Post-revolutionary America hovered on the brink of anarchy and even today, if we are honest, we often see private greed often overwhelming national interest.

Perhaps even more striking is our ambivalence about who we are and how we regard those who would join us. Many of those who strongly support the current push to expel foreign workers also employ them. They have good reason to do so because they often perform tasks that others do not do and/or work for wages that American citizens regard as exploitive. This is an old pattern in the American economy. The push to “send them back where they came from” would be damaging to the rest of us. As the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found in a study published on September 21, 2016,

Immigration is integral to the nation’s economic growth. The inflow of labor supply has helped the United States avoid the problems facing other economies [particularly Japan] that have stagnated as a result of unfavorable demographics, particularly the effects of an aging workforce and reduced consumption by older residents. In addition, the infusion of human capital by high-skilled immigrants has boosted the nation’s capacity for innovation, entrepreneurship, and technological change. Research suggests, for example, that immigrants raise patenting per capita, which ultimately contributes to productivity growth. The prospects for long-run economic growth in the United States would be considerably dimmed without the contributions of high-skilled immigrants.

And:

More than 40 million people living in the United States were born in other countries and almost an equal number have at least one foreign-born parent. Together, immigrants and their children comprise almost one in four Americans.

They are believed to have added about $2 trillion to the America’s economy during 2016.

Moreover, they are not a flood tide of illegals breaking down the barriers. Roughly, 1 million legal immigrants have arrived each year since 2001. And, rather than pouring in by hordes, the illegal immigrants have been balanced by emigrants each year since 2009. We have had in place for about half a century treaties and laws to extradite those who break our laws.

In short, the public discussion on foreign workers is inaccurate and the thrust behind the policy proposed by President Trump would damage the American economy. We are, after all, a nation of immigrants. Our only real difference is the timing of our arrival. We need to come to grips with the immigration issue both as a matter of economic well-being and, more important, as a matter of our civic health.

Seventh, that greatest of our conservatives, the very symbol of Republicanism and the ultimate realist, Alexander Hamilton, set out his analysis of the danger to our system and his prescription of what to do about it. On Monday, June 18, 1787 he addressed the delegates who were writing our Constitution. As his associate but opposite number, that great liberal James Madison, recorded Hamilton’s thoughts (in Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787), Hamilton began by asserting that the aim of government was “the happiness of our Country.”

Essential to achieving the stability and vigor of government that would contribute to happiness or at least well-being, Hamilton asserted, was “an active & constant interest in supporting” Government. By that, he meant that there must be “An habitual attachment of the people” to what aims to promote the public good. As reported by Madison, he did not go into detail, but he clearly aimed at putting aside parochial or immediate satisfaction. He was aware that the public will fracture on this issue: A concern with the whole body politic is always in danger because the legislature will “represent all the local prejudices” of their constituencies. Not much could be expected from its members.

But driving all the problems is human nature: “Men love power.” In the quest for power, they are likely to act not only against the national interest but even, out of ignorance of the covert aims and under the leadership of demagogues, against their own real interests.

Hamilton did not count on an enlightened or engaged public. He took what Plato thought of as an aristocratic view of the political process. His objective and probably that of all of the members of the Constitutional convention to create a government made up not of the people but of the people the recently emerged colonials regarded as their aristocracy. Many, probably most, Americans today regard the Founding Fathers’ emphasis on white, wealthy, native-born, Anglo-Saxon Protestants as reprehensible. Today while we at least proclaim our dedication to democracy --- made up of the demos or common people as the Greeks defined democracy – the Founding Fathers opted for a different form of government. Generally, Americans now find the lack of representation or even of concern for “people of color,” native Americans, ethnic minorities and the poor in the Constitutional convention wrong. Fortunately, the drafters of that great document made it flexible and even vague so that it could be adapted to fit our evolving ideas.

Of course, Hamilton could not have predicted our evolving ideas and probably would not have agreed with most of them. His concern was rather different. In the context of America in 1787, America was a failed state. To save it was Hamilton’s aim. That led him to emphasize structure. He believed in strong government as the best protection of society. His studies – and one of the striking features of the discussion at the Convention was the appreciation of other governmental systems -- convinced him that the British had found the best balance of “public strength with individual security.” That observation in itself showed the openness of his mind: after all, he should be credited with having saved Washington’s army from the British when it was on the point of being crushed and he remained Washington’s strong right arm. Clearly, he was a man of strong convictions but also of an open mind. Few statesmen in my lifetime would have dared make a similar acknowledgment of the virtues of an enemy.

He coolly continued that “in every community where industry is encouraged, there will be a division of it into the few & the many. Hence separate interest will arise. There will be debtors & creditors &c. Give all the power to the many, they will oppress the few. Give all power to the few, they will oppress the many. Both therefore ought to have [sufficient] power, that each may defend itself agst the other.” This, he contended, must be built into the system and, to survive, the system could not depend on an unstable public mood.

What Hamilton and the other delegates to that remarkable convention feared was precisely the rule of the incompetent (as they defined them) in the cause of the people. They aimed, as I perceive it, for a government made up of the elite acting, as Lincoln later put it, “for the people.” But, as I read their minds from afar, they could not so clearly say that. Just as “populism” is today “in the air,” so then was “democracy.” France was nearing the great and bloody revolution; the American union had fallen apart; the “people” had seen that their sacrifices had not brought the millennium. Everyone was distressed. There was even a mood to go back into the British empire. As the yellow press would later use the phrase, “he public was “seething.” They had to act quickly and to preserve what they saw as the essentials but to do so in a way that was palatable to the public. So they hit on a subterfuge: elections for the House of representatives would be direct; elections for the Senate would be indirect through state legislatures and elections for the presidency would be the preserve of men who, they at least hoped, would speak for the national interest, a “college of electors.”

That was not quite what Hamilton preferred, but he was sufficiently agreeable to it that he joined in the campaign to get the Constitution approved.

Eighth, Hamilton and Madison went from the Philadelphia Convention to organize the public mood to ratify the proposed Constitution. No one then had conceived of political parties as we think of them today. Rather there was a sense of colony or state interest and more generally of a division between the southern and northern populations. A somewhat overlapping division was recognized between those who wanted a strong federal regime and those who feared it and wanted to preserve a decentralized system. The one group, inspired by Alexander Hamilton, called themselves Federalists and, a few years later, their opponents, inspired by Thomas Jefferson, called themselves Democratic-Republicans.

But these terms were in part misleading. The collections of active men around Hamilton and later around Jefferson very little resembled what we think of as political parties today. This is not surprising because the writers of the Constitution, and particularly Hamilton and Madison, were hostile to “faction.” As Madison wrote in Federalist X, “Among the numerous advantages promised by a well-constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction…Complaints are everywhere heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens…that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties.” This was the message that President George Washington sounded in his Farewell Address.

However combinations or associations of the above description may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion…

Let me now take a more comprehensive view, and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party generally…

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

But, as Washington expected, parties grew. They were perhaps built into the system the Constitutional assembly had created as they were evolving in contemporary Britain. But they were very far from what we today think of as the great corporations of the Democratic and Republican Parties, controlling the process of candidate selection at all levels and mustering vast amounts of money to sway and mobilize voters. To my mind a sort of scale can be started when a member of my family, James K. Polk, surprisingly to the leadership, won the nomination, was elected and made his way to Washington: he had to pay his own way and upon arrival had to make his own hotel reservation at his own expense.

Those days are long past. Now we have political parties that are virtual governments, waxing and waning with the times, but unlike the English parties never really totally out of office because of the divisions of our system into the myriad offices of towns, counties and states. If one party loses control of the Senate or the Executive, it may still dominate the House of Representatives, governorships and legislatures of a number of states.

Just as significant: both the Democratic and Republican parties are essentially corporations, each with its own system of management and its own controlling figures. Each is, in effect, a fourth division in the triad that the Founding Fathers imagined. And each has pulled far from the concept they set out of our public life. It seems to me that one way or another, during the coming four years, both Parties must be redefined and their corporate tendencies must be reined in.

Ninth, I suggest is the needfor an ombudsman.

The built-in constraints to run-away and parallel government that existed at the end of the eighteenth century no longer exist. Truth be told, they were factors of weaknesses of American society, technology and geography that no longer exist. The comfortable division of power among the executive, legislature and judiciary has been breached. Something is needed to get us back to the system that made American politics work, at least generally, as Hamilton wanted for “the happiness of our country.”

Hamilton apparently thought that the College of Electors might perform this task. Many believe that it has not. But the core of the idea behind it remains. This is only an idea, but it seems to me that something adaptation of it to the tasks of a sort of Council of Elders, is worth examining. After all, such an idea and institution that has been recognized in human societies, long before we have any records.

What might it entail. Most employment of it has restricted it to Men and women beyond the age of ambition and who are assumed to have imbibed the spirit of their social and political system. In small societies, as far as I have observed, they could count mainly on prestige to enforce their decisions if such decisions were seen as “right.” In our very complex, diffuse and vast society, this would not work. Thus, such a group would have to have the power to indict acts of malfeasance. This power was given to the Congress in the Constitution but has proven insufficient. In our system as it has evolved, it falls in the Department of Justice but, although partially protected by allocation of powers to civil servants, it is a creature of the Executive which can be employed or silenced or rendered impotent. The ombudsman should be able to circumvent or override the political use of the justice system.

This is different from the court system Montesquieu and those of our Founding Fathers whom he influenced envisaged. The courts have the power to undo what has already been done but cannot play the proactive task of heading off acts that could do great harm but have not yet come into play. Nor can the occasional Special Prosecutors (as in Watergate); indeed, in various other dangerous undercutting of our system that occurred in recent years over actions in Vietnam (delaying negotiation to influence the election of Nixon), Iran (delaying of the release of hostages to influence the election of Reagan), the winning administration was able to quash inquiry.

Such an authority must, of course, have complete access to all necessary information and so be able to learn about false intelligence and malpractice. Thus it requires power of subpoena. But, above all, it must have the public trust. On the positive side, this means that it must have “voice” to speak directly to the public; on the negative side, it must be restricted to Constitutional issues to avoid being used to stifle differing opinions or to promote political factions.

As I say, this is only an undeveloped idea and one which may be useful only in demonstrating the area of danger to our system, but it seems to me that discussion of it might be of value.

Tenth, the unstable public mood is most dangerous on the issue of war. My reading of American history convinces me that we are a warring people. A fundamental feature of our national culture is fascination with war. War is what enabled us to compensate for or, time after time to overcome, our differences. The First World War integrated the German part of our society and the Second World War began the revolution that led Obama to the White House.

Attitudes toward war have played crucial roles in our evolution. They have energized our people, swept us across the Continent, gave us a taste of empire, enabled us to overcome powerful enemies. But, they have also led to great wrongs and even greater dangers. I suggest that we might think of war as being like a pistol. Firing it is sometimes forced upon us, but, even kept in the holster, it can be used by ambitious leaders to shape or control our way of life. Brought into play, it can threaten or destroy our civic culture.

War is not a new challenge to our system nor is it uniquely American, but it is, I believe, so urgent an issue today that we must understand all of its ramifications and effects as fully as possible.

More urgently, I suggest that it is basic to the what, consciously or unconsciously, will become the strategy of the Trump administration for at least the coming four years. It is likely to come into play very soon – “saber-rattling” already sounds ominously. Four years is a long time and the saber has been grasped by the administration and apparently is taken to be a solution to complex or intractable issues. We can expect crises to follow one another with little pause. However, interim events play out, I predict that war will be nearly certain when, as is likely, Trump prepares for reëlection. So at some length, let me consider war from two widely separated positions: first, the way past tyrants have used it and, second, the way our Founding Fathers feared it.

Hermann Göring, a great practitioner in the art of destroying governments and states, famously told his jailers after he could no longer play a lead role in the game of nations, how rulers can use war:

“…of course the people don't want war. Why should some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece? Naturally the common people don't want war: neither in Russia, nor in England, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But after all it is the leaders of a country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or fascist dictatorship, or a parliament or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the peace makers for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same in any country.”

War, as Göring saw it, is the trump card in the game of power politics.

I turn back the clock to the Constitutional convention and listen again to Hamilton.

Stability being Hamilton’s aim and a means to prevent ill-considered and unnecessary destructive action, Hamilton wanted both the Senate and the President to be elected “for life or at least during good behaviour.” He feared that if the President were periodically elected, he would use his power “to prolong [Madison’s emphasis] his powers [and] in case of war, he would avail himself of the emergency, to evade or refuse a degradation from his place.” In short, war could destroy the Republic and render inoperative the system the Founding Fathers were striving to put in place.

Madison warned that “Constant apprehension of war has the same tendency to render the head too large for the body. A standing military force, with an overgrown Executive will not long be safe companions to liberty. The means of defense agst foreign danger have been always the instruments of tyranny at home. Among the Romans it was a standing maxim to excite a war whenever a revolt was apprehended. Throughout all Europe, the armies kept under the pretext of defending have enslaved the people.”

How does one fall into war? As Hamilton saw the process it depended on the positioning of a strong man in an unstable place. Since even an enlightened people could be rushed into disastrous actions, the system must be formed in a way to obviate or lessen that danger. Hamilton read out to the Founding Fathers a list of his recommendations of which the sixth was that “The Senate [– not the fickle house or the ambitious president --] to have the sole power of declaring war.”

There has been much discussion since that time over the words “declaring war.” That power, written into the Constitution as Article One, Section Eight, Paragraph 11 is separated from the actual control of combat in Article Two, Section Two, Paragraph 1 which designates that “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States…” The question is where the two powers separate. Can the Commander in Chief commit what amount to acts of war without war being “declared?” This question remains with us today. Listen to what those wise men thought:

Pierce Butler of South Carolina wanted the President to have the power to declare as well as to carry out war since he “will have all the requisite qualities, and will not make war but when the Nation will support it.” But, James Madison and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts quickly “moved to insert ‘declare,’ striking out ‘make’ war; leaving to the Executive the power [only] to repel sudden attacks.” They distrusted the Executive who, they apparently feared would thus gain powers that he could use for his own purposes rather than those of the nation. Roger Sherman of Connecticut “thought it [the agreed wording, declare rather than make ] stood very well. The Executive shd be able to repel and not to commence war. ‘Make’ better than ‘declare’ the latter narrowing the power too much.” Oliver Ellsworth remarked that “there is a material difference between the cases of making war and making peace. It shd be more easy to get out of war, than into it.”

Constitutional lawyers disagree among themselves, but a reading of the sentiments of the Founding Fathers, at least as their memoirs, Madison’s account of the Constitutional Convention and the Federalist Papers suggest, there was a general fear that a standing or professional army would endanger and could destroy the civil government. Elbridge Gerry “thought an army dangerous in time of peace” and must be strictly limited . The question then arose as to how the military could be limited.

The delegate from Virginia, George Mason, argued that “limiting the appropriation of revenue [was] the best guard” against the aggregation of power by the military. James Madison commented that “…armies in time of peace are allowed on all hands to be an evil.” The delegate of South Carolina, while arguing for the necessity of a standing army, urged that “The military shall always be subordinate to the Civil power, and no grants of money shall be made by the Legislature for supporting military Land forces, for more than one year at a time.”

What has happened since those worthy citizens gathered justified Hamilton’s fears of presidential use of threat to build his own power and the widely-held sentiment that a professional army posed a danger to the civic system. Most presidents since their time have sought to expand the role given them in the Constitution and many saw the military as the means to do so; the professional military establishment, naturally as the Founding Fathers predicted, wanted also to expand its role in governing the republic.

None of the Founding Fathers could have foreseen the growth of what President Eisenhower called the military industrial complex although Alexander Hamilton, as I quoted him, foresaw the change that would come about when a society was industrialized. He did not go so far, but it seems to me that what was implicit is that the leaders of industry would themselves become an extra-Constitutional power, as it were, a fourth branch of government. Neither that transformation nor the enormous power given by control of the media and virtual corruption of what the Constitution treated as the first branch of the American government, the Legislature, could have been foreseen in 1787.

Nor could anyone at that meeting in Philadelphia have foreseen, although Hamilton presciently warned of the quest for power by the Executive, of a situation like we face today where the separate branches of government have been effectively amalgamated and where what Hamilton would have seen as non- or even anti-systemic power could play such a powerful role.

Nowhere is this role more powerful than in the ability of the president to initiate nuclear war. For over half a century, we have lived with the danger that a chief executive could, without any restraint or advice, order a first strike on any target or targets throughout the world. We have had instances when presidents were incapacitated (Wilson and Reagan) and even short of such extreme cases, all of us as individuals must be aware that there are days and nights when our judgment is impaired, headache, stomach upset, bout of flu, overindulgence, or other. And some of us are given to bouts of anger or depression from time to time.

I am certain that our Founding Fathers would have thought our total reliance on the continuous and never faltering good sense and morality of one man for, literally, the life of the Earth, is madness. Somehow, despite all the complexity of the issue, some way must be found to bring this power into systematic control or, the odds are, that we will eventually suffer a catastrophic event.

Getting our ship of state back under control is clearly a complex, even an all-consuming, challenge to the American people. It comes at a time when all the massed forces of money, perception of danger, ambition, greed and ignorance are against the accomplishment of the task. And, even beyond those is what the Founding Fathers realized was the greatest danger of all, the effect of war.

Had they faced what we face today, I think they would have said that above all we must avoid war. It could be the final blow in the struggle over American politics, civic culture and freedom. And as that great English conservative Edmund Burke commented, "All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing." Whether or not we value our heritage, we cannot escape our own best interests. The “buck stops with us.” We had better use these next years to protect ourselves and the future of our society. Let’ get at it.