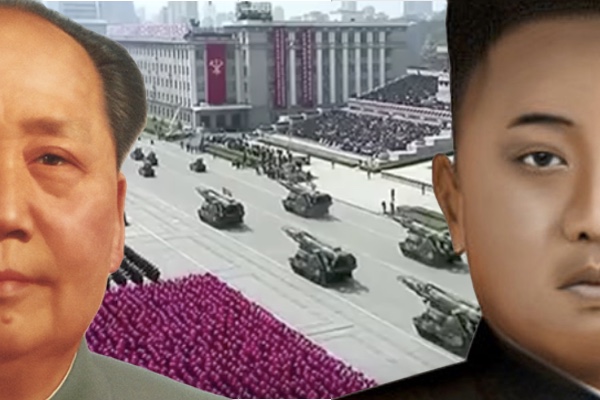

Once Upon a Time Mao Was also Regarded as a Crazy Personality Cult Leader with Nukes

Portrait of Mao Zedong - By Zhang Zhenshi (1914–1992), CC BY 2.0 Portrait of Kim Jong-Un - By User P388388 on Wikimedia Commons - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

Pyongyang is defiant and belligerent, while Washington seems in a dilemma. Most analysts agree “there is no silver bullet” to solve the Pyongyang problem, and diplomacy may be the only sensible way to reach a solution. Yet, the Vincent Strike Group is ordered to move into the troubled waters near the Korean Peninsula, which was followed by more hostile rhetoric from Pyongyang. Was Washington’s hyped-response to North Korea’s provocation warranted? It might be beneficial to look back into the “Beijing problem” in the 1950s and 1960s. After all, there are striking similarities between the current Pyongyang regime and the Beijing regime under Mao Zedong.

Just like Kim Jong

Un’s regime today, the Beijing government in the Mao years was also

a one-man dictatorship isolated from the international community. As

such, it was often grandiose and paranoid at the same time, and its

behavior was naturally unpredictable. In the politics of personality

cult, the leader’s image is everything; if he is seen as less than

heroic or even “chickened out” by external threat, his regime

will collapse. This is what Max Weber called “charismatic

authority.” Thus, external

threat often gives dictators a chance to show their heroism of

defiance, and to rally the people against perceived foreign threat.

To consolidate their rule, Mao and Kim would often provoke

international crises to enhance their standing domestically. Back

then, Washington considered the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as

a “rogue state” just like today’s Democratic People’s

Republic of Korea (DPRK). The

assumption of a “monolithic communist threat” was fashionable in

the US, while little attention was paid to the growing conflict

between Moscow and Beijing for almost two decades. That was until

1969 when the two communist giants fought against each other

militarily in the northern Manchuria border area. Moscow even

reportedly approached Washington to propose a preemptive strike to

take out China’s nuclear program. The Kremlin came to believe that

Mao was a mad man. That got the attention Richard Nixon and Henry

Kissinger who were looking for an honorable way to get out of

Vietnam. After twenty years of hostility, Beijing and Washington

started to pursue rapprochement. It was likely that this turn of

events could have happened earlier had Washington understood the

nature of Mao’s regime and Sino-Soviet relations better, and acted

accordingly.

Just like Kim Jong

Un’s regime today, the Beijing government in the Mao years was also

a one-man dictatorship isolated from the international community. As

such, it was often grandiose and paranoid at the same time, and its

behavior was naturally unpredictable. In the politics of personality

cult, the leader’s image is everything; if he is seen as less than

heroic or even “chickened out” by external threat, his regime

will collapse. This is what Max Weber called “charismatic

authority.” Thus, external

threat often gives dictators a chance to show their heroism of

defiance, and to rally the people against perceived foreign threat.

To consolidate their rule, Mao and Kim would often provoke

international crises to enhance their standing domestically. Back

then, Washington considered the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as

a “rogue state” just like today’s Democratic People’s

Republic of Korea (DPRK). The

assumption of a “monolithic communist threat” was fashionable in

the US, while little attention was paid to the growing conflict

between Moscow and Beijing for almost two decades. That was until

1969 when the two communist giants fought against each other

militarily in the northern Manchuria border area. Moscow even

reportedly approached Washington to propose a preemptive strike to

take out China’s nuclear program. The Kremlin came to believe that

Mao was a mad man. That got the attention Richard Nixon and Henry

Kissinger who were looking for an honorable way to get out of

Vietnam. After twenty years of hostility, Beijing and Washington

started to pursue rapprochement. It was likely that this turn of

events could have happened earlier had Washington understood the

nature of Mao’s regime and Sino-Soviet relations better, and acted

accordingly.

After the Korean War, the Washington-Beijing conflict kept escalating. Mao manufactured one international crisis after another to further his own revolutionary agenda at home and to export revolution abroad. Immediately after the Geneva Accord ended the first Indochina war, Mao launched the “Liberating Taiwan Campaign,” attacking the offshore islands of Quemoy and Matsu held by Taiwan’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). The Eisenhower Administration prepared the American people for the possible use of nuclear weapons in case Mao’s People’s Liberation Army attempted to conquer the territory held by the KMT. Moscow, however, promptly stood up to warn Washington that the Soviet Union would retaliate in kind if China were attacked by nuclear weapons. Thereafter, Beijing started its own nuclear program, and Moscow promised its support by providing a sample nuclear bomb. At the 1957 Moscow Conference of Communist and Workers’ Parties, Mao challenged the Kremlin’s new foreign policy line of peaceful co-existence and peaceful competition with the West by advocating continuing revolution. He even stated that a future nuclear war might kill half the world’s population, but socialism would prevail thereafter.

While Khrushchev was preparing for his US visit, Mao manufactured the second Taiwan Straits crisis by attacking two offshore islands again in 1958. Washington threatened to use nuclear warheads, and Moscow came to Beijing’s assistance again, although Mao did not inform Khrushchev of his action in advance. Mao in fact had no intention to clash with the Americans militarily at all; he provoked the crisis to make a statement against the Soviet policy of détente ahead of Khrushchev’s planned visit to Camp David. Not long after the Sino-Soviet alliance unraveled, and Moscow reneged on its promise to provide technical support in the Chinese effort to build a nuclear bomb. The Chinese nuclear program continued without Soviet support, and it succeeded a few years later in 1964. With the Vietnam War escalation and US bombing of North Vietnam, China stepped up its commitment to Ho Chi-min’s cause by sending many AAA units to engage the American bombers. Thanks, at least in part, to Chinese involvement, America lost the Vietnam War. However, the loss of South Vietnam did not trigger any “domino” to fall; instead, just a few short years after the last Americans left Saigon, the Hanoi-Beijing conflict erupted, leading to the Sino-Vietnamese border war in 1979. Could Washington have done better to take advantage of internal conflict within the Eastern bloc and to avoid costly war in Vietnam in the first place?

Bearing all this in mind, what could Washington learn from the recent past so that it would deal with the Chinese and North Koreans more intelligently? First of all, Washington has to understand the nature of the Pyongyang regime, and to learn to live with its unpredictable and provocative behavior, as unpleasant as that might be. The Beijing regime in the Mao years was far more dangerous and menacing than the Pyongyang regime today, and it became a nuclear power after 1964, while its armed force was engaged in a combat situation fighting against the Americans in Vietnam. If that kind of regime in Beijing did not present an existential threat to the US then a nuclear North Korea would not present such a threat either. Washington’s hardline approach and hostility toward Beijing over a period of more than 20 years only strengthened the PRC’s resolve to continue its radical revolution and to acquire its own nuclear bomb. On the contrary, the Sino-American rapprochement in early 1970s led to Deng Xiaoping’s visit to the US in 1979. A sweeping “reform and openness” program followed, which transformed China in the last three decades. Given the Chinese experience in the recent past, the Trump White House’s policy of threatening the use of force would likely be counterproductive; the pronouncement of “the age of strategic patience is over” may be premature.