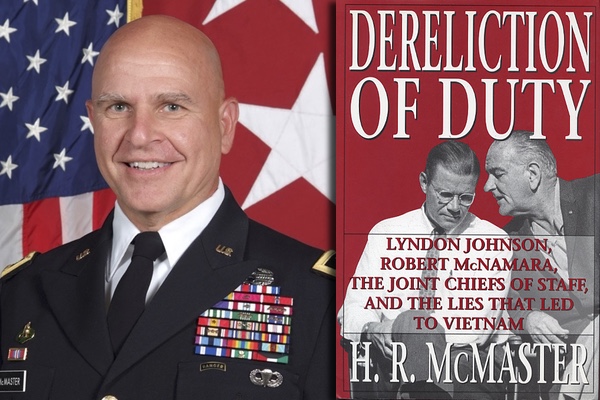

What Does H.R. McMaster’s Famous Book Tell Us About Him?

H. R. McMaster’s sudden elevation to policy prominence has prompted reflections that are in part personal. Herbert Raymond McMaster came to UNC-Chapel Hill in the early 1990s, a captain in his early thirties intent on working in the UNC-Duke military history program under the direction of Richard Kohn. A 1984 graduate of West Point, he had already made a name for himself during the first Gulf War by leading a bold tank charge that overwhelmed numerically superior Iraqi forces. I got to know him through course work and our shared interest in the Vietnam War, which landed me on his MA and PhD committees. By the time he defended his PhD thesis in 1996 it was clear to me (as Senator John McCain has put it) that McMaster was “a man of genuine intellect, character, and ability.”

He was also a man on the move (already clear in the rapid completion of his doctoral requirements) and a risk taker (also clear in a dissertation that took sharp aim at the Joint Chief of Staff). In 1994-96 he returned to West Point to teach and complete his dissertation (published as the book Dereliction of Duty in 1997). He moved on through the regular Army cycle of staff, school, and combat unit assignments, building his reputation as he went. Not afraid of the limelight, McMaster got considerable notice in 2005-2006 for his pacification strategy in Iraq, which prefigured the counter-insurgency boom that developed under the auspices of General David Petraeus.

He was also a man on the move (already clear in the rapid completion of his doctoral requirements) and a risk taker (also clear in a dissertation that took sharp aim at the Joint Chief of Staff). In 1994-96 he returned to West Point to teach and complete his dissertation (published as the book Dereliction of Duty in 1997). He moved on through the regular Army cycle of staff, school, and combat unit assignments, building his reputation as he went. Not afraid of the limelight, McMaster got considerable notice in 2005-2006 for his pacification strategy in Iraq, which prefigured the counter-insurgency boom that developed under the auspices of General David Petraeus.

His forthrightness and command of the public spotlight riled some senior officers. Having been promoted early three times in his career, his promotion to brigadier general was delayed twice and a third snub would have ended McMaster’s career. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates intervened, and a third review chaired by a distinctly friendly Petraeus finally got McMaster his first star in 2008. The next two followed in short order as he continued to burnish his reputation as a warrior-scholar. In the most recent and dramatic turn in his career, a floundering Trump administration tapped him to head the National Security Council. The resignation of retired Lt. Gen Michael Flynn had set off an urgent search for a replacement. After Navy Adm Robert Hayward refused the position, McMaster got the nod. In late February he traveled to Mar-a-Lago where the president introduced his new National Security Council head, who would remain on active duty while serving in the White House.

* * *

This rise to prominence of the warrior-scholar has also prompted me to look back at McMaster’s book and his involvement in the war on terrorism through my historian’s prism, especially my interest in the Vietnam War and U.S. foreign policy.

My own sense of Dereliction of Duty based on a fresh reading some twenty years since its publication and some twenty-one years since I read it as a dissertation is that it is impressively researched, clearly written, and strongly argued. It deserves the plaudits that it earned at the time and repays reading today. It has a two-part structure. The introduction and epilogue boldly indict the Joint Chiefs and their civilian masters. “The disaster in Vietnam was not the result of impersonal factors but a uniquely human failure, the responsibility for which was shared by President Johnson and his principal military and civilian advisers.”1 Lyndon Johnson was in McMaster’s eyes guilty of lying, manipulation, and subordination of Vietnam to his domestic agenda. The senior military leaders for their part failed in their duty because of their fixation on the parochial interests of their respective services and their “go-along-to-get-along” reluctance to challenge their commander-in-chief and his civilian advisers.

Between those bookends are some three hundred plus pages of careful, fresh, detailed, archivally-based treatment of the policy process — the exchange of memos, the meetings, and the inspection tours to Vietnam — that culminated in LBJ’s July 1965 decision to make a major U.S. troop commitment in Vietnam. In its detail and bite Dereliction of Duty brings to mind David Halberstam’s The Best and the Brightest (1972), another carefully marshaled indictment of the men who led the country into a disaster.

McMaster’s explanation for the Vietnam debacle was not the first to command attention of the officer corps, but it was arguably the one that resonated most strongly. By pointing to a failure of leadership on the part of the military’s most senior officers and a refusal by policymakers to respect military advice, Dereliction of Duty spoke to a deep sense of grievance within the military over the loss of life and institutional reputation resulting from flawed leadership. It became required reading.

Neither McMaster nor his readers seemed inclined to grapple with some hard “what if” questions. How would events have played out had the JCS stood up to LBJ? Would insistence on being heard have altered major decisions and led to a different outcome in the war? Or would standing up to LBJ have simply caused the president to further distance himself from the military, thus deepening distrust and dysfunction in civil-military relations?

A reading of McMaster’s book today evokes the same fundamental interpretive objection I had to his doctoral dissertation several decades ago. McMaster doesn’t give Lyndon Johnson a fair shake and in the process fails to understand the broad context in which policy was then — indeed is invariably — made. I accept the charge that the president was duplicitous, manipulative, and calculating. These were the traits of a great politician but also of a policymaker caught in an impossible situation that genuinely deserves to be called tragic. Johnson knew all to well why he was trapped. Vietnamese nationalism was a potent fuel for the resistance to U.S. intervention, and abetting that resistance were stout Chinese and Soviet allies. Documentation that came available even as McMaster was working on his project confirmed Johnson’s conviction that a U.S. invasion of the North would have triggered a dangerous international crisis and if not a nuclear confrontation then likely an expanded and prolonged ground war.

LBJ was also constrained domestically by a strong anti-communist consensus. Johnson feared with good cause that the abandonment of Vietnam and thus the blow to the bipartisan policy of containment would create a political uproar. Johnson worried about the threat from the Right even more than the one from the Left and was convinced that any concession would not only weaken him politically but also create a groundswell of support for a dangerous escalation of the war.

The only satisfactory course — the only imaginable course in the context of the times — was the safe middle if muddled option of doing just enough to keep the Saigon government afloat and hope that the fates would somehow favor the U.S. cause. In short, Johnson had an acute understanding of the limits of U.S. power from the outset that far exceeded that of the senior military. Johnson needed the help of military leaders both professionally and politically, but he could not as the price of that help abandon his safe if unsatisfactory middle course of gradual escalation.

There is ample evidence on Johnson’s views. Take for example my favorite: his taped telephone comments to Robert McNamara on 21 June 1965 on the eve of his major troop deployment:2

It’s going to be difficult for us to very long prosecute effectively a war that far away from home with the divisions that we have here [in the United States], particularly the potential divisions. . . . I’m very depressed about it ‘cause I see no program from either [Department of] Defense or State that gives me much hope of doing anything except just prayin’ and gasping to hold on during the monsoon [season] and hope they’ll [the Vietnamese Communists will] quit. I don’t believe they ever goin’ to quit. I don’t see how, that we have any way of either a plan for victory militarily or diplomatically.

After this remarkable summary of the difficulties facing the U.S. role in in Vietnam, the president pronounced abandoning Vietnam impossible. “I don’t think we can get out of there with our treaty like it is and with what all we’ve said. And I think it would just lose us face in the world, and I shudder to think what all of ‘em would say.” These last observations reflect the hold of commitments to a communist-free Vietnam going back more than a decade and to his determination not to allow an opening for the Goldwater Right to whip up anti-communism at home, to promote a dangerously hard-edged foreign policy, or to undermine the Great Society program.

That McMaster in his inaugural outing as a historian drew up an indignant indictment of the policy process and downplayed the broad international and domestic context in which policymakers functioned was understandable. It was his Army that got mauled in Vietnam as a result of Johnson’s decisions. And in any case a dissertation and first book should not be expected to draw on the experience of a lifetime but rather to demonstrate skill at sound research and clear exposition. That is what Dereliction of Duty did in spades. But what the author now running the NSC is going to need is much more of that breadth of view missing earlier. Policy does not take shape in a vacuum. The interests of other powers matter and so too does the state of political play at home. Is this an insight McMaster has taken on board?

* * *

Not much in the warrior-scholar’s engagement in the post-9/11 war on terrorism, first in Iraq and then in Afghanistan, offers a clear answer to that question. Nor do we know whether he thinks that U.S. policymakers have been more successful in waging the war on terrorism than they were in Vietnam and whether he actually anticipates a more favorable outcome after a decade and a half of sustained engagement, military and otherwise.

McMaster’s Iraq experience began in mid-2005 as the U.S. occupation faced growing resistance. As commander of the 3rd Armed Cavalry Regiment, he made his goal the pacification of Tal Afar, a city of 200,000 in northern Iraq west of Mosul. The population was mainly ethnic Turkmen, a majority of whom were Sunni and the minority Shia. The city had changed hands several times. Following the U.S. invasion in 2003, insurgents had wrested control, only to be pushed out by the U.S. Army in 2004 and then to return in 2005.

McMaster brought with him to Tal Afar ideas about the conduct of counter-insurgency formulated while working on General John Abizaid’s Central Command staff during 2003-2004. He was guided by two sources, both based on the European colonial experience, that were to become required reading among those drawn to counter-insurgency around this time. One was David Galula, a French officer who had fought in the battle to hold Algeria in the late 1950s and then written up lessons learned. The other was the British pacification program in Malaya during the 1940s and 1950s.

McMaster together with Petraeus and other champions of counter-insurgency failed from the start to recognize how deeply steeped in colonial assumptions Galula and other sources were and how neo-colonial their objectives were. Like the French and the British, they were asserting dominance over other peoples and assuming the right to shape their future. The counter-insurgent crowd also conveniently downplayed the idiosyncratic reason for the success the British had in Malaya: the insurgents were ethnic Chinese without significant international support and easily isolated from the country’s majority Malay population. Either an unquestioning sense of mission or a deep sense of national exceptionalism blinded them to their awkward role as liberators trying to impose order and instill new values and institutions.

The sudden Army infatuation with counter-insurgency did at least lead to the sensible realization that pacification was less military than political and that force had to be employed with restraint. According to an illuminating study by Mac Owens, McMaster concluded that the way forward was to focus on the civilian population, “isolating residents from insurgents, providing security, building a police force, and allowing political and economic development to take place so that the government commands the allegiance of its citizens.” The critical assumption underlying this program was that the population was passive, taking a wait-and-see attitude. Adroit handling could win that population over and leave insurgents isolated, demoralized, and vulnerable.3

McMaster started the operations at Tal Afar first by schooling his troops in a new norm of limited force and respect for civilians and then by building a berm around the city to channel movement to a few checkpoints. With the stage set, he dispatched 5,000 Iraqi and 3,800 American soldiers into the city to eliminate insurgents, set up some thirty command posts, recruit and train police, deliver basic services (roads, electricity, water, schools), calm Sunni-Shia sectarian conflict through power sharing arrangements, and address popular grievances.

This far-reaching, deliberate approach along with heavy investment in generators, school supplies, training for police, and funding for city operations proved a success — but only as long as the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment was there to run the show. When it departed in mid-2006 leaving Iraqi forces in charge, the security situation deteriorated. Sectarian violence returned and became routine by early 2007. In 2014, three years after the withdrawal of all U.S. combat units from Iraq, ISIS captured the city and today still holds a portion of it. From the current perspective, Tal Afar reveals in microcosm the limits rather than the promise of counter-insurgency.

The Afghanistan phase of McMaster’s education began in 2010 when he was assigned to the International Security Assistance Force in Kabul. His job was to curb if not stop blatant, pervasive, crippling corruption in an Afghan government heavily sustained by international funding. This time there was not even a short-term glimmer of success. In time-honored fashion a government heavily dependent on outside support for survival turned aside a hard-charging foreign reformer. Indigenous collaborators knew all too well that they were indispensable to the outsiders and could extract a price for their collaboration.

Despite disappointing results, McMaster assumed the role of the “go-along” general of the sort he had criticized so harshly in Dereliction of Duty. Before his departure in 2012 he publicly professed optimism about the general direction of the campaign against the Taliban. Attacks were down, Afghan security forces were more numerous, school enrollments were up, and communications had improved as cell phones proliferated. He concluded with the cheery view that the next step forward was to consolidate these gains politically and psychologically.

Despite McMaster’s happy talk, it has long been evident that the nation-building project in Afghanistan had gone off the tracks. Stephen Walt, a scholar of international relations with a strong realist outlook, has very recently pronounced that project “an endless, costly, and unrealistic effort with no clearly discernible endpoint and little hope of success.” Government security forces have suffered heavy casualties as they have taken over more and more of the fighting. The insurgency either controls or has a foothold in about a third of the country’s 402 districts. All this, Walt reports, after the United States has “spent more than $65 billion on training along with nearly $120 billion in reconstruction efforts and nearly a trillion dollars in actual war costs.”4

How would McMaster today compare the Vietnam policy he indicted in his book with the failed record of counter-insurgency in which he has played so signal a role? What lessons does McMaster take from his ultimately disappointing efforts in Iraq? How does he assess a situation in Afghanistan now that seems to diverge dramatically from his earlier, rosy assessment? How does he evaluate the investment of American life and treasure in those two countries with so little to show for it? The answers might tell us much about the mindset and the assumptions of the new head of the NSC and how he might evaluate the proposals directed at his boss from agencies across the executive branch.

* * *

But first the warrior-scholar has to gain control of an agency that functions as a miniature version of State and Defense Department combined with the CIA. McMaster suffered an early setback when he tried to fire his senior director for intelligence (a thirty-year-old Flynn protégé, Ezra Cohen-Watnick). Jared Kushner and Stephen Bannon supposedly intervened with the president to block the move, and Trump had Cohen-Watnick reinstated. But McMaster pressed ahead. He revised the NSC principals list to exclude Bannon and to include at the table the JCS, the directors of National Intelligence and the CIA, the UN ambassador, and the Energy Secretary. Moreover, McMaster brought the Homeland Security Council within his purview and got he got his deputy inherited from Flynn, K. T. McFarland, appointed ambassador to Singapore.

The next challenge is to socialize an undisciplined president in the kind of systematic staff procedures so ingrained in the military culture. This has already proven no easy matter. His boss has a short attention span, an antipathy to reading, a tendency to shoot off his mouth, and an instinctive preference for quick, informal decision-making. His pronounced inexperience is compounded by his antipathy to expertise and especially intelligence and by his heavy reliance on family and loyalists. McMaster’s efforts to tutor, guide, and curb have not surprisingly made him in Trump’s estimate “a pain.” Perhaps most serious of all is the president’s serial, seemingly compulsive lying with its insidious effects which McMaster himself underlined in Dereliction of Duty, most forcefully in a quote by Thomas Jefferson: “He who permits himself to tell a lie once, finds it much easier to do it a second and third time, till at length it becomes habitual; he tells lies without attending to it, and truths without the world’s believing him. This falsehood of tongue leads to that of the heart, and in time depraves all its good dispositions.”5 McMaster has personally felt the corrosive effects of the “falsehood of tongues” after gamely spinning Tump’s mishandling of intelligence during his meeting with the Russians.

Beyond staff control and the president’s dysfunctional style lies that greater challenge of what course to pursue in that large part of the Muslim world now in upheaval, not to mention in eastern Europe and Northeast Asia. The serial U.S. failures there are notable and the way forward not obvious. Is the United States so hopelessly entangled that there is no choice left but to try to hold Afghanistan and Iraq together while playing whack-a-mole against opposition groups raised up by the diverse, pervasive, and dynamic currents of political Islam. Walt has asked, “What would you do if your boss ordered you to teach a sheep to fly?” McMaster presumably knows that sheep can’t fly, but what will he tell the president? Will he succumb to the “can-do” spirit familiar from the Vietnam-era JCS? Would Trump welcome a “no-fly” declaration? He has been outspokenly critical of nation building and presumably is unhappy with money going down a rat’s hole abroad when the needs at home are so great. But he also likes winning and is uninterested in the intricate diplomacy that would be required to bring the regional powers (Turkey, Israel, Iran, and Saudi Arabia) as well as Russia into some kind of accord that might help to calm a much agitated neighborhood.

The greatest challenge of all is arguably the declining U.S. position as a world power. Slippage is evident at home in the erosion of civic comity and consensus, in declining educational standards relative to peer countries, and in the failure to invest in human welfare and infrastructure. Slippage is also evident in the steady rise of regional challengers that goes back to the Cold War era. The pronounced multi-polar nature of the international order today leaves U.S. policymakers constrained in general and frustrated by an inability to control developments in key regions around the world. Finally, U.S. hegemonic legitimacy has suffered repeated blows. Claims to leadership turn hollow and become more expensive without willing followers. When it comes time for the NSC to offer some sense of a grand strategy suited to difficult times, what will it recommend? Following some version of “America First” that promises an end to foreign entanglements while making Americans feel proud of their country? Or resuscitating the old orthodoxy of global leadership, broad regional engagement, and economic integration shaped during the Cold War and still much favored today by the policy community? Or exploring some third course that takes into account the vast transformations effected by globalization over recent decades?

Andrew Bacevich, a retired Army officer critical of recent U.S. foreign policy, has expressed doubts that McMaster has the chops to confront these overarching challenges. He would have to shift from thinking in narrow military terms to imagining a realistic grand strategy not only for the Middle East but for world affairs in general. “McMaster is a resourceful and demanding military leader. As a field commander, he has exhibited impressive tactical skill. As a staff officer he has filled high-profile assignments both at home and abroad . . . . For all that, he remains a professional soldier, not a global visionary.”6

But that judgment may be beside the point. It misunderstands the role of the National Security adviser, which is more about creating a process for making decisions that work for the president than serving up a grand design for him to embrace. If there is to be a grand strategy for the United States, it has to come from the president. The ultimate challenge of arriving at a sense of how the world works and how the U.S. ought to fit is thus one not for the National Security adviser but for his boss. Without that sense the president will have difficulty knowing what questions to ask and ultimately how to use the NSC to refine, test, publicly articulate, and implement his vision. The best McMaster can do is introduce Trump to the possibility of thinking in a more deliberate, expansive, and coherent fashion. And this is well within McMaster’s demonstrated skill set. It would be no small achievement — and one with distinctly ironic overtones — if the warrior-scholar turned policymaker could help Trump become as astute and engaged in the making of policy as LBJ was in his time.

* Thanks to Judith Pulley for the opportunity to test the observations laid out here, to James Huskey for a close, critical reading of a draft, and to Richard Kohn for a reassuring vetting. This post was updated on 20 May 2017.

1 Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies that Led to Vietnam (New York: HarperCollins, 1997), 334.

2 From a secretly recorded conversation held by the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, Austin, Texas, and widely reproduced in books on the Johnson presidency.

3 Mac Owens, Naval War College study, May 2009, available at www.fpri.org/article/2017/03/counterinsurgency-bottom-colonel-h-r-mcmaster-3rd-armored-cavalry-regiment-tel-afar-spring-fall-2005/ (accessed 9 April 2017). See also Jon Finer, “H.R. McMaster is hailed as the hero of Iraq’s Tal Afar. Here’s what that operation looked like,” Washington Post, 24 February 2017, available at www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2017/02/24/h-r-mcmaster-is-hailed-for-liberating-iraqs-tal-afar-heres-what-that-looked-like-up-close/? (accessed 2 April 2017).

4 Walt in Foreign Policy magazine online (28 March 2017) available at foreignpolicy.com/2017/03/28/mission-accomplished-will-never-come-in-afghanistan-taliban-al-qaeda-trump/ (accessed 29 March 2017).

5 Dereliction of Duty, 85.

6 Bacevich appraisal at www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/the-duty-of-general-mcmaster/(accessed 2 April 2017).