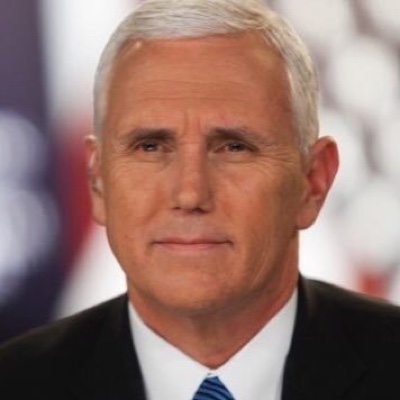

Mike Pence’s Big Decision

The clouds over the White House have become much darker after the empanelling of a grand jury on the Russia investigation. However remote the path to impeachment may be, it is not unthinkable. In a White House known for its in-fighting, leaking and its general dysfunction, this development has to be causing most West Wing occupants to think carefully about their future. The veterans at least will see that no one among them is invulnerable to the shake-up that is now under way. No one, that is, except Mike Pence, the only person in the executive branch who can’t be fired. He can have other things in store for him, however, such as being caught up in a conflict between his loyalty to the president and his loyalty to the truth. But that’s a ways down the road.

“I am vice

president,” John Adams said on becoming the first occupant of that

office. “In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.” The

perceptive Adams understood that the office was created as a

constitutional afterthought for one purpose and one purpose only: to

provide for a new chief executive should the incumbent die or be

removed. With little else to do but wait, Adams soon called it “the

most insignificant office that ever the mind of man contrived,” and

escaped to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts whenever he could.

“I am vice

president,” John Adams said on becoming the first occupant of that

office. “In this I am nothing, but I may be everything.” The

perceptive Adams understood that the office was created as a

constitutional afterthought for one purpose and one purpose only: to

provide for a new chief executive should the incumbent die or be

removed. With little else to do but wait, Adams soon called it “the

most insignificant office that ever the mind of man contrived,” and

escaped to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts whenever he could.

Most subsequent vice presidents subscribed to Adams’s assessment. When asked what he did, a frustrated Nelson Rockefeller put it this way: “I go to funerals. I go to earthquakes.” Over time the office slid into obscurity, surfacing for the most part only as the subject of ridicule. That changed dramatically, however, in the late 1970s when President Jimmy Carter and his vice president, Walter Mondale, sought to make the office useful instead of ornamental. They set about to redefine its function without altering its constitutional purpose, and over four years created what has become known as the modern vice presidency. As chief of staff to Vice President Mondale and a member of president Carter’s senior staff, I was privileged to be present at the creation of this newly conceived office and to watch it evolve ever since.

Carter and Mondale agreed that the latter would become an across-the-board advisor to the president on foreign and domestic policy as well as a trouble-shooter whenever the president wanted his engagement and advice. To make this arrangement work, Carter gave Mondale unprecedented access to his person and to all information to which he himself had access; Mondale was welcome to attend any meeting on the president’s schedule.

The arrangement worked very well, primarily because of the confidence they had in each other. It worked so well, in fact, that five succeeding presidents adopted the Mondale model essentially intact, with appropriate variations for his needs as well as the experiences and abilities of the vice president. Recent presidents have invariably seen their vice president as one of their chief assets, and thus the modern vice presidency has become institutionalized, in practice if not in law, as an integral part of the chief executive’s office. There is no better example of how well this can work than that of President Obama and Vice President Biden during the past eight years.

It’s not apparent the extent to which Donald Trump and Mike Pence have studied this history or how seriously they have discussed their official relationship. Is there an understanding between them, either verbally or in writing? If so, we don’t know about it.

One of the underlying principles of the modern vice presidency is that immersion in the policy- and decision-making processes of the White House should be useful to the vice president if, God forbid, he or she should succeed to the presidency. With growing uncertainty now in the air, these questions take on even greater importance,

The other major change regarding the nation’s second highest office occurred earlier and had to do with how vice presidents are selected. When national party conventions were introduced early on, they were tasked with nominating presidential and vice presidential candidates. The presidential nominee, even if he was the incumbent president, might be asked for his advice but in the end the choice was solely the prerogative of the convention; it was one of the few substantive responsibilities of the convention delegates, and they jealously guarded it.

In 1940, however, Franklin D. Roosevelt, having significantly expanded the powers of the presidency already and now running for an unprecedented third term, challenged the Democratic convention’s traditional practice by insisting it nominate as his running mate Henry Wallace. But Wallace was anathema to many party regulars, especially conservatives. They took the matter to a hard-fought floor fight during which FDR threatened to decline his own nomination if Wallace’s wasn’t approved. Wallace was finally approved – barely – and thus was born a change in our political structure that would have huge consequences in the future.

One of the most profound consequences, of course, had to do with to whom did the vice president owe his loyalty going forward once both were in office? The answer is obvious: to the president who chose him. With both major parties following FDR’s lead in future years, thus began the inexorable shift of the office from the legislative to the executive branch, a shift that is now effectively complete.

Loyalty is a big thing for presidents, sometimes a very big thing. Watching Donald Trump for six months, it sometimes seems as though loyalty is the only thing, and in fact he is a self-described “loyalty freak.” His firing of James Comey probably illustrates this best, but it’s certainly not the only example. Every president has a right to expect loyalty from everyone on his official team, including his vice president. While “disloyal” vice presidents can’t be fired, they can still be marginalized and they invariably know it. The office is one of total dependency, and its occupant can easily be cut out-of-the-loop: Lyndon Johnson kept Hubert Humphrey from attending meetings on Vietnam after the vice president disagreed with LBJ on that volatile issue. Gerald Ford partially sidelined Nelson Rockefeller after his top staffers, Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, excluded Rockefeller from key policy discussions. Ironically, George W. Bush did much the same to Cheney after the latter established a national security power center in the vice president’s office largely independent of the National Security Council, and often pursuing different goals.

A vice president’s loyalty to the man who selected him, or to his own views on a particular issue where he differs with the president, can be, and often is, tested. It’s almost always resolved in the president’s favor because that’s part of the bargain when signing on; there’s only one president at a time, and his views inevitably prevail. If the disagreement is one of principle, the vice president has the option of resigning, but only one occupant of the office has ever chosen that course: John C. Calhoun left office in 1832 over a strong disagreement with President Andrew Jackson on whether states could “nullify” acts of Congress (the only other vice president to resign was Spiro Agnew in 1973 when President Richard Nixon forced him out before he would be criminally charged).

A vice president’s loyalties are never as conflicted as when the president’s tenure is in question, as it is increasingly now with Trump. Only once before has this conflict been so apparent, and that of course was when Gerald R. Ford replaced Agnew as Nixon’s vice president under the 25th amendment in late 1973. Ford, a staunch Republican and the party’s leader in the House, would serve in the office for only eight months, during the run-up to the climax of the Watergate scandal. The politically seasoned Ford had to know what he was getting into, but it still took him a while to sort out his loyalties. During his first month he “vigorously defended” the Nixon Administration, according to records in the Miller Center, a respected affiliate of the University of Virginia that specializes in presidential scholarship and political history.

It’s not clear what caused Ford to change course in January, 1974, but it’s likely that he became disillusioned with the lack of honesty and openness in the White House, traits he had always honored, He fiercely resisted efforts by Nixon’s people to make him “as much as possible a loyal member of the White House staff.” He would not be subsumed, and he deliberately began to distance himself from anything he thought might compromise his integrity. Ford never criticized Nixon personally but he called his chief advisors “an arrogant, elite guard of political adolescents.” Coming from someone seen as a decent and principled Midwesterner whom virtually everyone in Washington liked and admired, the comments stung; they served to isolate him from the Watergate story that was increasingly eating away at the Nixon presidency.

When it became known that Nixon had recorded conversations in the Oval Office that were possibly incriminating, he refused to turn them over to the special prosecutor who had subpoenaed them, arguing they were subject to executive privilege. Ford urged Nixon to turn them over anyway, but it was not until the Supreme Court ordered him to do so that he finally relinquished them. They were indeed incriminating, prompting the House to initiate impeachment proceedings and prompting Ford to say that no one could now maintain that Nixon was “not guilty of an impeachable offense.” The game was over; Nixon resigned and Gerald R. Ford was sworn in as president.

The country needed healing from Watergate, and Gerald Ford was able to provide a good deal of it because of who he was at his core as revealed by the way he emerged from the vice presidency with his integrity intact. Nixon had a claim on his loyalty, but Ford concluded that in this instance the truth, the Constitution and the American people had a higher claim. And for that decision we owe him a great deal. He was a good man, and he served the country extraordinarily well when it needed him.

Mike Pence’s circumstances today, it can be argued, are very different, and events may well prove that to be true. But history sometimes does repeat itself, and when it does, it can help to look back and see how others managed it. Again, most vice presidents struggle at some time with where their loyalties lie, but it’s only rarely that conflicting claims on one’s loyalty are so strong because the stakes are so high. Working for a president who prizes loyalty above everything else, it would be surprising if the vice president hasn’t already given this approaching dilemma some prayerful thought.

From all indications Pence has been a very loyal vice president, always eager to lead the applause for whatever Trump wants done, even when it changes from day to day. Probably the most obvious example of his desire to please the president occurred when he led an obsequious cabinet in heaping unsolicited praise on Trump. The president was clearly pleased but likely not surprised by the awkward tributes; few such celebrations occur in this White House unscripted. And just recently Pence pushed back vehemently when it was suggested he was preparing to run for president in 2020; no, he insisted, he is totally loyal to the Trump agenda.

Mike Pence has been remarkably successful in keeping a low profile while others in the Trump camp have been engulfed by new, almost daily revelations regarding the Russia investigation. But that’s not likely to last: One of these days Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s team will almost certainly put Pence (and others) under oath and ask whether it’s true that President Trump asked them all to leave the Oval Office on February 14 of this year so that he could have a private conversation with then-FBI Director James Comey. Contradicting Comey’s public testimony, Trump has said he did not ask them to leave, signaling to Pence and the others that maybe they should concur. How they choose to answer under oath, however, will have much to do with whether the president is seen as having obstructed justice. This scenario puts Pence in an unenviable position, but luckily he has at hand the lessons of another Midwestern vice president who navigated these rapids before him.

Vice presidents matter more than ever, and it’s often about loyalty.