Why I Decided to Make Hatred the Subject of a Talk to the General Public

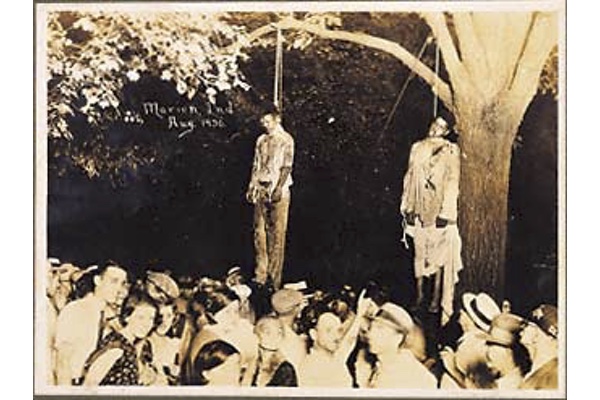

An image from Without Sanctuary

Click HERE for HNN's Complete Coverage of Charlottesville.

The outbreak of raw bigotry sanctioned at Charlottesville should remind us that this is nothing new. We have not changed racist attitudes as much as driven them underground. Until very recently, that is. A short while ago, speaking to a public gathering about the theme of our preferably forgotten past, the audience remained surprised to learn of two key prejudices that culminated in violence: Nativist riots along with the attendant vandalism and the widespread nature of lynching.

Why choose these points as a focus for a lecture to the general public? In the case of the American Nativist movement, we never really learn, or emphasize, the anger directed toward other European immigrants “of the wrong sort.” Catholics, notably the Irish, symbolized the clear and present danger to the American Republic; this political movement found support across the spectrum of class and education. The long-standing anti-Catholic prejudice had arrived with English settlement. The Reformation’s politics animated Protestant colonial legislation as assemblies continually disenfranchised Catholics. Into the twentieth century, American remained suspicious—if not openly hostile—to Catholic candidates.

The animosities of European culture never died in the New World. Simply taking a three-thousand mile trip across the ocean did not upend prejudices rooted in lifetimes of culture. Indeed, in some places, a mixed marriage remains one between a Catholic and a Protestant. While this may strike modern sensibilities as quaint, it bears witness to the red thread that runs through American culture and politics. Christian bigotry directed at other Christians continues as sanctioned behavior, however largely removed from today’s realm of public policy.

Far deeper and producing more sustained violence over much of our history remains race hatred. Once again, we fail to teach or emphasize the social sanctions to this act that has unofficially enforced legislative doctrine. For most people, lynching remains an abstraction; violence against innocents reverberates in the abstract rather than as a concrete result of vigilante crowds. Only recently has the occasional college survey text daring to include a photo. Rarely do survey texts go out of their way to mention largescale assaults on African-American communities in the early twentieth century: East St. Louis and Chicago, Illinois; Tulsa, Oklahoma, or Rosewood, Florida.

Dramatic examples for teaching Americans about our bitter past can be found in the photographic documentary, Without Sanctuary. Here, the editors and commentators (James Allen, Hilton Als, John Lewis) present a compilation of souvenir photo postcards that bear witness to, and celebrate, community acts of racial violence. Well dressed gatherings, neatly combed hair, a sense of accomplishing a civic good characterizes the crowds in all these examples. As the Civil Rights movement remains in the distant past for many Americans, especially those of college age and younger, so too does the history of racial violence to cow and control a population.

Few topics have been driven home more clearly and viscerally than these images. They also bring a direct connection to the recent violence against black church congregants, the debates on Black Lives Matter, the continued shouting match about kneeling during the national anthem. We do not all share the same history. We do not all share the same reference points. Yet we can acknowledge a common inheritance of deep-seated religious and racial prejudice that continues to shape our lives as a nation.

Only by teaching the deep taproots, unashamedly can we hope to explain why Charlottesville undermines us as a nation; only when we honestly confront lynching across the entire U.S., not merely as a Southern phenomenon; only then can we make inroads on the hatred that is permanent.