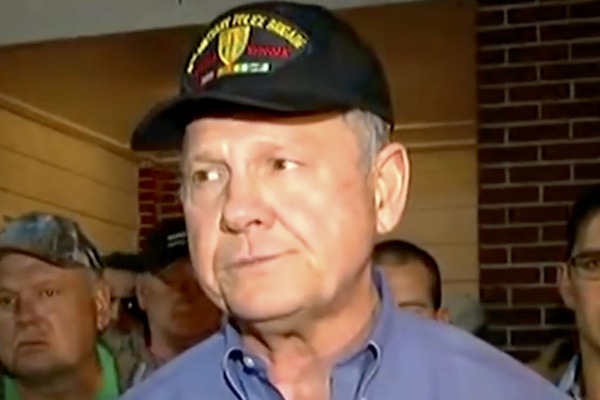

Can a 1903 Supreme Court Case Put Roy Moore in the Senate?

If Roy Moore narrowly defeats Doug Jones in next week’s Senate race, he may have an obscure 1903 Supreme Court case to thank. The case, Giles v. Harris, upheld Alabama’s successful campaign to prevent African Americans from casting ballots despite the constitutional guarantee of the right for black people to vote. Its ramifications can be felt to this day: about 15 percent of otherwise qualified African American residents of Alabama have been barred from voting in recent elections. In a state where 90 percent of eligible blacks vote Democratic, that can make the difference in next week’s closely watched Senate election.

Alabama’s unequal approach to voting can be traced to its 1901 constitution, drawn up to prevent black citizens from voting. The president of the convention that drafted the constitution, John B. Knox, declared at the beginning of the meeting: “And what is it that we want to do? Why it is within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this State.” The new state constitution, written entirely by white males, was remarkably effective. Although more than 180,000 black residents were eligible to vote in 1900, the number dropped to about 3,000 after adoption of the constitution.

The tactics embedded in the state constitution included the imposition of a poll tax, literacy tests, and a grandfather clause favoring white residents who had previously registered. In addition, the constitution included a provision permanently disenfranchising anyone convicted of a crime involving “moral turpitude.” It was left up to local officials to define that term, and they used that opening to wield it against African Americans. Within two years, criminal voting restrictions disenfranchised nearly 10 times as many blacks as whites.

One of the black residents who lost the right to vote was Jackson Giles, a political activist in Montgomery who had voted from 1871 to 1901 and headed an organization called the Colored Men’s Suffrage Association. Giles turned to the courts, seeking an injunction on behalf of himself and more than 5,000 other black residents of Montgomery County to require voter registration officials to enroll them. The case of Giles v. Harris made its way to the Supreme Court in 1903, provoking one of the more idiosyncratic but consequential decisions in Court history.

Writing for a majority of six justices, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. dismissed Giles’s case for two reasons. First, in a bit of Catch-22 logic, he ruled that the Court was required to enforce voting rights only in constitutional voting systems. If Giles was correct and the Alabama voting laws were unconstitutional, then the Court had no jurisdiction to intervene. “If, then, we accept the conclusion which it is the chief purpose of the bill to maintain,” Holmes asked, “how can we make the court a party to the unlawful scheme by accepting it and adding another voter to its fraudulent lists?”

He then proceeded to his second — and perhaps more fundamental — reason for ruling against Giles: the Court had limited power in the racist South. “If the conspiracy and the intent exist, a name on a piece of paper will not defeat them,” he conceded. “Unless we are prepared to supervise the voting in that state by officers of the court, it seems to us that all that the plaintiff could get from equity would be an empty form.”

The decision had a profound impact as southern states were emboldened to adopt increasingly effective tactics at disenfranchising their black citizens. Curiously, however, it largely disappeared from constitutional law histories, perhaps because the opinion by Holmes rested on such strained logic. In an influential article in 2000 in Constitutional Commentary, University of Michigan law professor Richard H. Pildes concluded that the case had been “airbrushed out of the constitutional canon.” Regarding the conclusion by Holmes that the Court could not require registration in an unconstitutional voting scheme, Pildes pilloried it as “the most legally disingenuous analysis in the pages of the U.S. Reports.” He and other scholars also believe the Court could have made a difference had it overturned anti-voting laws in Alabama and other states.

Be that as it may, the Giles case has influenced policy for generations, right up to the current day. Supreme Court Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter in 1946 famously urged the Court to stay out of the “political thicket” and avoid getting involved in voting rights disputes — an admonition that continues to haunt the justices as they weigh disputes over gerrymandering and voter ID laws.

And the case continues to affect Alabama. Poll taxes and literacy tests are now barred, but the voting system still excludes those convicted of crimes of moral turpitude. The Supreme Court in 1985 ruled that the state could no longer apply that term to misdemeanors. But officials continued to use the subjective term to deny voting rights to hundreds of thousands of felons, most of whom were poor and African American. An analysis of the 2008 presidential election concluded that the law prevented 250,000 Alabamians from voting that year, including thousands who were likely eligible but were kept from registering because of the confusion and debate over which crimes consist of moral turpitude, which has led to differing standards for voter registration in the state’s 67 counties. As recently as last year, some 15 percent of otherwise eligible African Americans lacked the right to vote, according to a study by The Sentencing Project.

Under mounting political and legal pressure, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey signed a law earlier this year to better define moral turpitude and create a list of fewer than 50 crimes that it encompasses. The list included such crimes as murder, kidnapping, and sexual abuse, although critics noted that it left off crimes such as political corruption that are associated with more affluent offenders. But the Birmingham News reported in October that county registrars remain confused over the new law and that nonprofit organizations and voting rights advocates were finding that people continue to be wrongly barred because the law was not being properly followed.

It’s impossible to say how this legacy of discrimination will affect next week’s Senate race. But African Americans make up about 27 percent of the state’s population, and a disenfranchisement rate of 15 percent equates to almost 4 percent of the overall vote. Of course, the numbers are not that clear-cut: some whites have also been disenfranchised (although at a much lower rate) and additional ex-felons will be able to vote in this election under the new moral turpitude law. But with the current polling average in Real Clear Politics giving the edge to Moore by less than 3 percent, the extent of black disenfranchisement may well make the difference.

This is a historically important election. If Jones were to win, the Republican advantage in the Senate would shrink to 51–49. With the Senate so tightly split over such critical issues as tax cuts and health care, a Democratic pick-up of even a single seat could stall the GOP agenda. An additional Democratic vote could also block President Trump’s more controversial judicial appointments. If the Supreme Court’s decision in Giles v. Harris is any indication, those judgeships can influence policy for many generations.