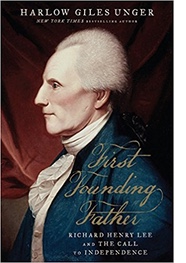

Review of Harlow Giles Unger’s “First Founding Father: Richard Henry Lee and the Call to Independence”

Jesus had twelve apostles and a

baseball team fields nine men, these numbers are immutable. But how

many “founding fathers” did our country have: seven, or nine? Or

maybe thirty-nine, if you list all the delegates who signed the

United States Constitution.

Jesus had twelve apostles and a

baseball team fields nine men, these numbers are immutable. But how

many “founding fathers” did our country have: seven, or nine? Or

maybe thirty-nine, if you list all the delegates who signed the

United States Constitution.

In his new book, First Founding Father: Richard Henry Lee and the Call to Independence, author Harlow Giles Unger seeks to document the many ways in which Lee, an often-overlooked Virginia politician, made significant contributions to the American drive for independence.

Unger is an expert on early American political figures having written biographies of John Quincy Adams, Lafayette and Henry Clay. Unger’s new book is centered on the thesis that Richard Henry Lee (1732-1794) was the “first” Founding Father in a chronological sense. Unger writes that he was the first prominent Virginia political leader to “call for independence, first to call for union, and the first to call for a bill of rights.”

Yes, but who or what defines a “Founding Father?” There appears to be some dispute within the community of historians about who qualifies.

Wikipedia cites historian Richard B. Morris, a winner of the Bancroft Prize, and his “Seven Who Shaped Our Destiny: The Founding Fathers as Revolutionaries. Morris included Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. He omitted Richard Henry Lee.

The Encyclopedia Britannica entry lists ten names, adding John Marshall, Samuel Adams and George Mason, but leaving out John Jay and also Richard Henry Lee.

General readers will find the travails of the Richard Henry Lee described in an interesting, subject-friendly manner. He was an investor in the Ohio Land Company with George Washington, blew off his left hand in a gun accident and carried on a secret correspondent with Pierre Beaumarchais, the French playwright and a spy for King Louis XV.

Richard Henry Lee may not have been a charismatic figure like Jefferson or Washington, but he played a key role at the Continental Congress and as a signer of he Declaration of Independence.

However, the author fails to explore an important aspect of Lee’s life: his role as a major slaveholder and how this experience shaped his actions as a political leader.

The fact that all of the Virginia-based Founding Fathers owned slaves has been well documented. Many historians have also pointed to the Virginians’ slaveholding experience as a motivation in seeking independence from Great Britain. Jefferson and Patrick Henry often depicted the white American colonists as being “slaves” to the British king. Richard Henry Lee also used this imagery, telling his friend Beaumarchais that the British “press us with war, threaten us with danger and slavery.”

Richard Henry Lee certainly had first-hand knowledge of slavery, coming from one of the wealthiest families in Virginia. He grew up on his father’s great estate, Stratford Hall, a huge mansion overlooking the Potomac River and the headquarters for managing the family’s 4,000 acres of prime farm land.

It is obvious that enslaved black workers made a substantial contribution to the Lee family fortune, but we learn nothing about them. How many black slaves did the Lee family own? Where and how did they live? Unger provides no information on this important aspect of his subject’s life.

For example, historian Henry Wiencek’s 2012 book Master of the Mountain, Thomas Jefferson and his Slaves, takes a critical look at this founder’s treatment of the black workers. Wiencek notes that “The Monticello machine operated on a carefully calibrated violence.” He documents how Jefferson hired overseers known for their cruelty, “issued orders to impose a vigor of discipline (on Monticello’s output) and then spread a fog of denial over the whole business.”

Unger implies that Richard Henry Lee consistently opposed the concept of slavery. He notes that as a young man in the 1757 session of the House of Burgesses, he criticized the slave trade (but did not go so far as to advocate abolition). Lee introduced a motion to heavily tax the importation of slaves into the colony and attacked the ‘iniquitous and disgraceful traffic within the colony of Virginia.”

Heavily taxing or banning the importation of slaves was a much less controversial issue than abolishing slavery itself. By this time, Virginia held 150,000 enslaved blacks, about 40 percent of its total population. Virginia was a major exporter of slaves to other southern states, particularly South Carolina and Georgia.

Unger credits Lee with a major anti-slavery role at the Confederation Congress. The author says Lee convinced the Congress to “pass the most remarkable act in its history,” the Northwest Ordinance, which prohibited slavery in the land north of the Ohio River.

Unger accepts the conventional view that the passage of Northwest Ordinance in 1787 was a major victory for the emerging, anti-slave movement in the Northern states.

Contemporary legal scholars have raised questions about the motivations of Southern political leaders in accepting the act. George William Van Cleve, of the University of Virginia, explored the Southern political leaders’ machinations in his 2010 book A Slaveholders’ Union, Slavery, Politics and the Constitution in the Early American Republic. Van Cleve notes that the Southern congressmen were probably “indifferent” to the Northwest Ordinance, since it “did not adversely affect, and might even protect, their section’s vital interest.”

Unger does not explore this possibility. Was Richard Henry Lee, whose family wealth came from the exploitation of black workers, really committed to abolishing slavery? Interestingly, when Lee later served as a United States Senator (1789-1792) and in the Second Congress (1792), he took no further role in seeking to limit slavery.

The author reports that when Richard Henry Lee died in 1794, “slaves carried his plain wooden casket to its grave,” but there is no word if the black workers were later manumitted. One must assume they were not. George Washington, of course, did specify in his will that his slaves be freed, while Jefferson’s estate sold off many of the enslaved workers at Monticello, in the process breaking up many longstanding black families.

First Founding Father provides a well written, entertaining portrait of a man living in an exciting era, but it leaves important questions unanswered. If Richard Henry Lee is to be considered a Founding Father, his role as a slave owner and the impact of slave-ownership on his political philosophy deserves serious consideration.