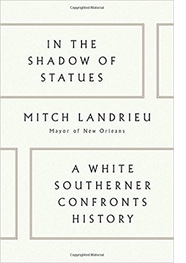

Review of Mitch Landrieu’s “In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History”

On

May 19, 2017, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu delivered an address

explaining the decision of his administration to remove four

Confederate statues from city property. While the removal of the

statues generated considerable controversy within the Crescent City,

Landrieu’s eloquent speech confronting the burdens of Southern

history and providing a framework for racial conciliation received

national acclaim, leading some pundits to suggest that Landrieu seek

the Democratic nomination for President and challenge the racial

divisiveness of President Donald Trump. And Landrieu enjoys a

Louisiana pedigree that encourages such political ambitions. His

sister, Mary served as a U. S. Senator from the state, while his

father, “Moon” was also Mayor of New Orleans and fought to

desegregate the city during the 1960s. Following in the footsteps of

his family, Mitch served as a state legislator from 1988 to 2004 and

was then elected Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana. In 2010, he won

election as Mayor of New Orleans and is now completing his second and

final term of office in that position. In chronicling the work of

his administration in rebuilding New Orleans following the

devastation of Hurricane Katrina and the corruption of former Mayor

Ray Nagin, Landrieu does come off as a politician who might be

interested in seeking higher office—and there is much to admire in

the Landrieu record. For historians, however, the real value of In

the Shadow of Statues

is how Landrieu expands upon the ideas of his May 2017 speech to

confront the shadow that slavery continues to cast over Southern and

American history.

On

May 19, 2017, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu delivered an address

explaining the decision of his administration to remove four

Confederate statues from city property. While the removal of the

statues generated considerable controversy within the Crescent City,

Landrieu’s eloquent speech confronting the burdens of Southern

history and providing a framework for racial conciliation received

national acclaim, leading some pundits to suggest that Landrieu seek

the Democratic nomination for President and challenge the racial

divisiveness of President Donald Trump. And Landrieu enjoys a

Louisiana pedigree that encourages such political ambitions. His

sister, Mary served as a U. S. Senator from the state, while his

father, “Moon” was also Mayor of New Orleans and fought to

desegregate the city during the 1960s. Following in the footsteps of

his family, Mitch served as a state legislator from 1988 to 2004 and

was then elected Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana. In 2010, he won

election as Mayor of New Orleans and is now completing his second and

final term of office in that position. In chronicling the work of

his administration in rebuilding New Orleans following the

devastation of Hurricane Katrina and the corruption of former Mayor

Ray Nagin, Landrieu does come off as a politician who might be

interested in seeking higher office—and there is much to admire in

the Landrieu record. For historians, however, the real value of In

the Shadow of Statues

is how Landrieu expands upon the ideas of his May 2017 speech to

confront the shadow that slavery continues to cast over Southern and

American history.

Landrieu describes how even though he came from a progressive white Southern family, he was unable to really perceive the weight of Southern history upon black citizens until jazz musician Winston Marsalis explained to the Mayor that he could not support a city revitalization project until offending monuments to the Confederacy and legacy of slavery were removed from city property. The ultimatum from Marsalis forced Landrieu to re-examine some of his assumptions regarding Southern history. Landrieu confessed that while growing up in New Orleans he paid little attention to the city’s Confederate monuments, but after talking to many of his black constituents, and taking a walk in someone else’s shoes, the Major recognized that to blacks the statues provided a daily reminder of how white Southerners who fought to preserve an institution that terrorized their ancestors were celebrated by the city. Landrieu had his staff investigate the Confederate monuments and found that most were constructed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to bolster Jim Crow segregation, while more recent Confederate memorials were erected during the 1950s and 1960s as part of a racist resistance to the Civil Rights Movement.

The Mayor persuasively argues that the monuments are a perversion of Southern history and attempt to perpetuate the mythology of the Lost Cause in which the Civil War was fought to preserve an ideal agrarian civilization in which blacks and whites lived in harmony. Thus, the cause of the war was not slavery but the defense of state rights against Northern aggression. This mythology seeks to erase the beatings, rape, labor exploitation, and separation of families that characterized American slavery. The Confederate monuments are also used to discredit Reconstruction in which the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution were depicted as the “rape” of the South by freedmen, Yankee “carpetbaggers,” and poor Southern whites—a distortion of history also perpetrated in influential Hollywood films such as Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone With the Wind (1939).

In addition to confronting the reality of Southern history and challenging the mythology of the Lost Cause, Landrieu insists that the legacy of slavery is alive and well today in the racial inequality of a city such as New Orleans. Landrieu documents how the destruction of Hurricane Katrina revealed the vulnerability of the black community in New Orleans who lacked the resources to evacuate in wake of the storm. The Mayor also deplores the violence in the black community which all too many whites seem willing to accept, seemingly endorsing the perspective of the Black Lives Matter movement when he asserts, “Perhaps, as a nation, we have bought into an evil notion—that the lives of these mostly young African American men killed everyday have less value and thus don’t deserve our urgent attention” (150). Fewer guns, better schools, more jobs, and a more equitable distribution of resources are needed to address these issues, but confronting the reality of the American past is also part of the solution.

Thus, Landrieu believes that just as it was essential for Germans to come to grips with the Holocaust following World War II, white Southerners must acknowledge the connection between Confederate monuments and the brutal institution of slavery that contributes to contemporary racism. Landrieu insists, “The shadow these symbols cast is oppressive. It is in this broad context, that people must now understand that the monuments and the reasons they were erected were intended to not affirm life but to deny life. And in that sense, the monuments in a way are murder” (159).

The Landrieu administration targeted four Confederate memorials for removal. The Mayor found an obelisk celebrating the 1874 uprising of a White League militia against the legitimate Reconstruction government to be especially unsettling, racist, and historically inaccurate. Though beloved by many Southern whites, Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis had little direction connection with New Orleans, and Landrieu hoped that the removal of their statues might not elicit great protest. The Mayor was more concerned with a memorial to native son General P. G. T. Beauregard whose post-Civil War political career encouraged racial reconciliation. Compromise and healing, however, were not the theme of the memorial that featured a mounted general waving a sword and leading his Confederate troops into battle in defense of slavery. Beauregard would have to go as well, but Landrieu laments that he underestimated the resistance to the removal of any monuments. The Mayor and his family, along with contractors for the removal, were confronted with death threats. Despite such vehement opposition, Landrieu displays no regrets about his decision to dismantle the racist symbols of the Lost Cause, concluding, “Politics does not provide many moments for an elected official to take a moral stand, realizing that you may well pay a political price in doing so but you know in your heart that you’ve done something that will make you a better human being” (199).

While the core of Landrieu’s book concentrates upon the question of Confederate monuments, a chapter addresses the rise of David Duke in Louisiana politics during the 1980s. Landrieu relates how he worked with both Republicans and Democrats in the Louisiana legislature to oppose the racially divisive agenda proposed by Duke. The former Klan leader has praised Donald Trump for championing the rights of white Americans, and Landrieu finds parallels between Trump and Duke, writing, “Donald Trump is not a Nazi, yet he has courted white nationalists as Duke did, and like Duke, he speaks and tweets a fountain of lies, lying as naturally as normal people try to be truthful” (82). In highlighting how he helped to foil Duke’s agenda in the Louisiana legislature, Landrieu appears to suggest that he might have the experience to challenge the divisive politics of President Trump on the national stage.

Regardless of whether he decides to seek high office, Landrieu is an articulate voice for confronting the centrality of race to the American experience. Landrieu grew up in a prominent white Louisiana family that challenged racial segregation in the state, yet in his everyday life he failed to recognize the symbolic presence of New Orleans monuments commemorating slavery and racism. It took the vision of Winston Marsalis to open Landrieu’s eyes to the shadow cast over his city by Confederate monuments. It is time for Southern whites to join Landrieu in acknowledging the symbols of oppression which they have erected on public squares and parks throughout the region. Confronting the history of slavery should provide a platform upon which to address the troubling legacy of racism within American society.