Woodrow Wilson Is Misremembered. This Has Warped Our Foreign Policy for a Century.

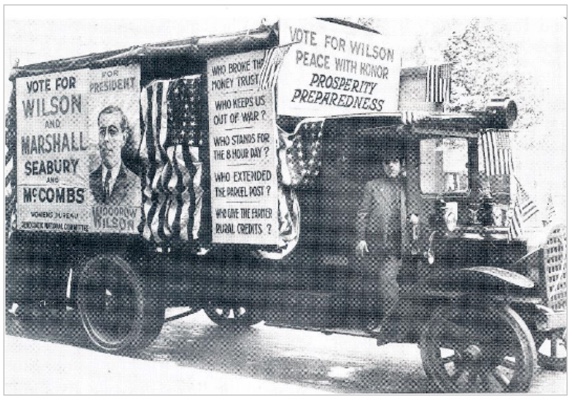

Wilson campaign vehicle, New York City, March 1916: “Who Keeps Us Out of War?”

World War One marked a turning point in human history. Modern weapons produced such high levels of destruction, death, impoverishment, and misery that war itself became an atrocity.

George Duhamel, a French army surgeon in the war, reflected that “war has become an industry, a mechanical and methodical enterprise for killing. Some of the most brilliant minds of a civilization devoured by geometry had labored for generations to ensure that death could be dealt on a mass scale with exactitude, logarithmic detail, dial-times, millesimal, calculated velocity.”

U.S. entry into the war did not change this gruesome reality. Indeed, the U.S. joined the race to produce more lethal weapons. The U.S. initiated a chemical weapons program in 1917 that involved more than 1,900 scientists and technicians, making it the largest government research program in American history up to that time. Winford Lee Lewis, the director of the Offensive Branch of the Chemical Warfare Service unit at Catholic University, justified the program as the most efficient and economical means to winning the war and stated that Providence would give the most advanced people the best gas.

U.S. entry into the war did not change this gruesome reality. Indeed, the U.S. joined the race to produce more lethal weapons. The U.S. initiated a chemical weapons program in 1917 that involved more than 1,900 scientists and technicians, making it the largest government research program in American history up to that time. Winford Lee Lewis, the director of the Offensive Branch of the Chemical Warfare Service unit at Catholic University, justified the program as the most efficient and economical means to winning the war and stated that Providence would give the most advanced people the best gas.

Was it necessary for the U.S. to enter the war?

Most American historical accounts have portrayed Woodrow Wilson as a reluctant warrior who tried but failed to keep the U.S. out of war; then once committed, pursued war to a successful conclusion. Such accounts generally cite as justifications for entry Germany’s adoption of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 1, 1917, and the Zimmerman note – a secret diplomatic communication from the German Foreign Office, revealed on March 1, that proposed a military alliance between Germany and Mexico if the U.S. declared war on Germany. Wilson’s larger rationales for intervention – to protect “the rights of all mankind,” to make the world “safe for democracy,” to secure “peace without victory” – have been treated as sincere, if utopian ideals. Wilson has also been credited with the birth of the League of Nations, even though the idea had been gaining popularity in the U.S. and Great Britain for a decade before Wilson endorsed it in May 1916.

The historian Robert Hannigan notes that the common portrayal of Wilson as one driven by “disinterested altruism” and “an unwavering commitment to principle . . . should never have gained the kind of authority it has, above all because its origins lay precisely in how the president advertised himself.” We agree. Wilson’s reputation as a peacemaker is undeserved. Rather than being suddenly thrust into war, the president took the nation into war, step-by-step.

● Soon after the war began, the Wilson administration unofficially aligned the U.S. with the Allied Powers, providing Great Britain and France with arms, ammunition, food, manufactured goods, and large loans.

● After initially offering to mediate the conflict, President Wilson took no action in this direction and furthermore rejected a number of opportunities to work in concert with neutral nations to promote mediated peace negotiations.

● The administration selectively applied the principle of “neutral trade rights,” tolerating the British blockade that shut off U.S. trade with Germany while threatening war if Germany reciprocated, not merely against U.S. merchant ships (attacks were rare before February 1917), but against British and French merchant and passenger ships.

● Between September 1915 and March 1916, Wilson’s personal envoy, Edward House, engaged in secret negotiations with British Foreign Affairs Secretary Edward Grey to bring the U.S. into the war under the false pretense of holding a peace conference. Although the plan was never put into effect, it was approved by President Wilson, indicating his willingness to go to war.

● Once Wilson was re-elected in November 1916, having claimed credit for keeping the U.S. out of war, he refused to undertake measures to actually keep the nation out of war. He did not prevent or even warn U.S. passengers traveling on belligerent ships in war zones, knowing that the loss of American lives would arouse the American war spirit.

● The Wilson administration’s furtive movements toward war were reinforced by the growing U.S. economic stake in an Allied victory, including the repayment of billions of dollars in loans.

On April 2, 1917, President Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, asserting that the “present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind.” Wilson presented the situation as if there was no other option. Yet there was a practical alternative: require that U.S. cargoes be delivered by British merchant vessels instead of American vessels. Senator George Norris of Nebraska, who voted against the war resolution, made this point on the Senate floor on April 4, saying, “We might have refused to permit the sailing of any ship from any American port to either of these military zones.”

The fact that the United States itself was not in any danger of attack meant that the most reliable justification for war, national self-defense, was lacking. President Wilson thus chose to embellish his justifications for war with grandiose ideals. Like campaign promises before an election, they were intended to persuade the public rather than guide policymaking. Among his glittering ideals was the promise of a more peaceful world order following the war via a new League of Nations. Yet the formation of the League did not require U.S. entry into the war. The U.S. could have just as well advocated for it as a neutral nation.

Wilson used idealism as a propaganda tool to overcome long-standing resistance to U.S. involvement in European wars. Once war was declared, he created an official propaganda agency to amplify his views and furthermore signed repressive laws to stifle dissent and imprison peace advocates, in effect, making democracy unsafe in America.

Wilson’s misplaced legacy as a peacemaker also arises from his “Fourteen Points” speech in January 1918. Wilson made a magnanimous statement in the prologue, but not one of his fourteen points actually promised to prevent harsh measures after the war. Berlin asked the U.S. to initiate peace negotiations based on the Fourteen Points in the vain hope that Wilson would block or mitigate the punitive demands of Britain, France, and Italy. Yet with the U.S. having suffered less than 2 percent of all Allied fatalities, Wilson was in no position to do so.

The economist John Maynard Keynes, who was part of the British delegation in Paris in 1919, wrote of Wilson: “It was commonly believed at the commencement of the Paris Conference that the President had thought out, with the aid of a large body of advisers, a comprehensive scheme not only for the League of Nations but for the embodiment of the Fourteen Points in an actual Treaty of Peace. But in fact the President had thought out nothing; when it came to practice, his ideas were nebulous and incomplete. He had no plan, no scheme, no constructive ideas whatever for clothing with the flesh of life the commandments which he had thundered from the White House. He could have preached a sermon on any of them or have addressed a stately prayer to the Almighty for their fulfillment; but he could not frame their concrete application to the actual state of Europe.”

Many of the details of the First World War have been forgotten, but Wilson’s idealistic justifications have remained a fixture in U.S. foreign policy. At a critical time in the expansion of American power and influence in the world, Wilson imbued this expansion with a set of rationales deeply rooted in American identity and ideology. Future U.S. leaders would return again and again to this wellspring of sacred principles, justifying every kind of war and foreign intervention in the name of freedom and democracy.