The Inspiring Campaign We All Need to Remember at this Horrible Time in Politics

There are many reasons to worry about American democracy and candidate conduct is among them. Much campaign behavior does little to raise political discourse. Slogans and sound bites replace thoughtful discussion, candidates flatter loyal audiences, misleading messages and attack ads seem more common than thoughtful dialogue over public policy.

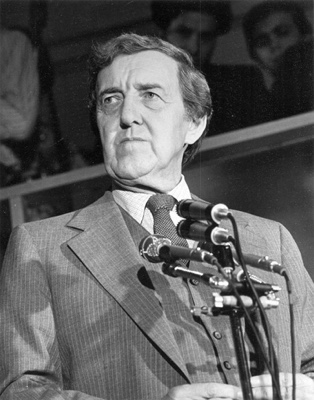

Although these deficiencies appeared once again in 2018, they are not inevitable features of political campaigns. Such is the lesson from Edmund S. Muskie’s 1968 vice-presidential campaign which in 2018 experienced its golden jubilee. Muskie outperformed not only the other candidates for national office that year but virtually every other national candidate in his and probably most life times. He did so by discussing issues and basic American values in a thoughtful and candid way. Rather than tell audiences what they wanted to hear, Muskie tried to persuade them through rational discussion regarding what he thought they should think. Muskie’s ticket narrowly lost but his vice-presidential campaign was highly effective and provides a model for 21st century America.

Although these deficiencies appeared once again in 2018, they are not inevitable features of political campaigns. Such is the lesson from Edmund S. Muskie’s 1968 vice-presidential campaign which in 2018 experienced its golden jubilee. Muskie outperformed not only the other candidates for national office that year but virtually every other national candidate in his and probably most life times. He did so by discussing issues and basic American values in a thoughtful and candid way. Rather than tell audiences what they wanted to hear, Muskie tried to persuade them through rational discussion regarding what he thought they should think. Muskie’s ticket narrowly lost but his vice-presidential campaign was highly effective and provides a model for 21st century America.

Muskie’s campaign as Hubert H. Humphrey’s running mate began as an impossible undertaking. The Democratic ticket faced numerous obstacles including division over the war in Vietnam, disillusionment after the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy, and Humphrey’s tarnished reputation. The party was financially broke and fractured with liberal supporters of Senator Eugene McCarthy disposed to stay home and ethnic and working class Democrats drawn to Governor George Wallace’s third party campaign. All Muskie had to do was introduce himself to America, win over the McCarthyites on the left and the blue collar and ethnic Democrats drifting to the right, and make Humphrey look good.

As police and protesters violently engaged outside the Democratic convention with rocks, billy clubs, and tear gas Muskie introduced himself to America with an acceptance speech that spoke of the foundations of a pluralistic society built on trust (“It means learning to trust each other, to work with each other, to think of each other as neighbors. It means diminishing our prerogatives by as much as is necessary to give others the same prerogatives.”) The speech, which Muskie dictated late that afternoon, was more college lecture than traditional convention speech but it echoed themes of Muskie’s lifetime of public service.

Whereas Richard M. Nixon and Wallace, and their running mates, Governor Spiro T. Agnew, and General Curtis Lemay respectively, embraced a “love it or leave it” mindset which associated dissent with disloyalty, Muskie championed constructive protest as inherent in the First Amendment and American tradition. He told Midwestern high school students that as Americans they were “privileged to kick the government around.” With that privilege comes “the duty and responsibility of using your heads, your hearts, your capacity for understanding, to do what is best for everyone concerned.”

Muskie’s performance at the Washington, Pennsylvania County Courthouse on September 25, 1968, was a metaphor for his campaign. When angry anti-war protesters, many from nearby Washington and Jefferson College, exercised their constitutional right to verbally kick the Democratic vice-presidential candidate around, Muskie invited a heckler to speak from the podium for 10 minutes with the understanding that the crowd would then hear Muskie for equal time. Muskie listened as the designated speaker advocated the politics of the street over the ballot box, and intervened to restore decorum when traditionalists jeered the provocative message. Muskie then told the audience why he believed in the American democratic system and encouraged the students to participate as citizens “to contribute to what must be done that the rest of us have not yet been able to do.”

To fat cat groups, Muskie often defended the long-haired, unruly youths who challenged establishment values. Muskie told these Chablis and brie gatherings that the young had “honest doubts” about the American system which often closed doors to the disadvantaged, that many “inequities,” “are your fault and mine.” Citizens should listen seriously to youthful critics and encourage their meaningful participation to improve America.

But Muskie did not coddle the college crowd. He told campus audiences of white, privileged students that he did not share their enthusiasm for the proposed all-volunteer army which would concentrate military service on the poor and blacks. He preferred a lottery which would spread the risk more equitably and contribute to democratic decision-making regarding war. And he admonished students to focus not just on the war but on other issues, to respect those who didn’t share their views, to accept, but work to change, democratic outcomes they dislike, and to build, not simply tear down.

Muskie frequently appeared before ethnic, working class audiences whose members, though traditionally part of the FDR coalition, were tempted by Wallace’s candidacy which spoke to, indeed fanned, their resentment about the racial policies of the Johnson administration and the decisions of the Warren Court.

Muskie told those gatherings of his father, Stephen Marciszewski,a Polish immigrant who became a tailor in Maine in the early 20th century. He had come to America, Muskie said, looking for “equality and opportunity” and had seen his hopes realized because in America “[s]trangers were accepted.” To make America “the land of opportunity that we came here to find, “all Americans had to work towards “a united America,” not “a divided America.” Real safety and real security came from freedom, not from walls. Would we continue to have an America built on trust and freedom or one built on distrust and hatred?

My father did not come here looking for fear; he came here to escape fear and to find freedom. He did not come here looking for hatred; he came here to escape it and to find freedom. He did not come here seeking to deny other people opportunity; he came here to find it for himself, thinking it was available to all people who lived in America. He came here believing that freedom here was freedom for everyone.”

By campaign’s end, Muskie was, in the words of presidential campaign historian Theodore White, “an almost immeasurable asset” to Humphrey’s campaign. The Democrats sent Muskie to crucial battlefields, ran televised ads using the vice-presidential choice as a reason to vote Democratic, and had Muskie fly cross-country to appear in the televised campaign finale. A prominent political cartoon depicted Muskie as a runner carrying Humphrey.

To be sure, Muskie brought an excellence to public service that few can match. Yet what also made his campaign special was his willingness to behave as a leader, not a supplicant, and his ability to give authentic voice to the best ideals of American constitutional democracy.

Muskie treated his listeners as adults who deserved to hear, and were capable of responding to, rational, fact-based discussions. He was a teacher who tried to persuade listeners, not a panderer who found inspiration in the biases, emotions, and fears of his listeners. Muskie saw political communication, not as a hierarchical activity in which candidates read applause lines from a teleprompter to supporters, but as an, interactive exchange in which candidates spoke, listened, learned, and answered, not simply to acolytes but to skeptics, critics, and reporters. Muskie held frequent press sessions and answered audience questions. The press was not the enemy of the people, but a necessity of government of, by, and for, the people. To Muskie, information and ideas were the tools of civil discourse and civil discourse was the indispensable instrument of democracy and constitutional government. He often said that “It is better to discuss a question without settling it than it is to settle a question without discussing it.”

Muskie had a deep understanding of, and commitment to, America’s best ideals, which he recognized as the national fabric, and he used his candidacy to express them regularly and with rarely matched eloquence. For Muskie, pluralism did not simply describe America but explained its strength. There was greatness in a country that welcomed immigrants, that let a Polish tailor Marciszewski become Muskie. Those Americans by choice and their children and grandchildren made, sustained, renewed and enhanced America’s greatness.

Freedom was the prescription for national greatness. “We are perhaps the prime example of a society which was created on the assumption that if you allowed the individual citizen to develop his full capacities, that he can contribute to a rational discussion and understanding and solution to our problems,” Muskie said. Just as democratic leadership compelled accountability, democratic citizenship imposed continuing duties and demanded responsible behavior, not simply a willingness to accept compromises but a commitment to work towards sensible accommodations to create and preserve a union built on mutual trust.

Muskie’s vice-presidential campaign was one of the few shining moments of the difficult year of 1968. It left a legacy of what a campaign and candidate should be like and modeled values upon which the survival of American democracy depends.

© Copyright Joel Goldstein 2018