What a Japanese-American soldier’s thirty-year secret can teach us about race, war, and loyalty

Masao Abe with his Congressional Gold Medal. Photo Credit: Kathie Abe

The Thirty-Year Secret

Sometimes, stories of heroism reveal themselves in the most unusual and humble ways. That was the case with Masao Abe, a second generation Japanese-American, or Nisei. Masao served in World War II as an interpreter with the Military Intelligence Service (MIS), an operation credited for shortening the war in the South Pacific by two years. Masao recalled memories from World War II with clarity, as though events had taken place the week before. At the age of 91, Masao began to share his story until he passed away in 2013 at the age of 96.

Revealing his WWII experience wasn’t something Masao could have done when he was in his thirties, forties, or even fifties. The MIS operation was considered classified, so much so that discussion pertaining to the MIS was forbidden for years. In fact, these restrictions weren’t lifted until the 1970s. While other soldiers, even the Nisei soldiers who formed the 442nd, could speak about their part in American campaigns, MIS soldiers had to remain completely silent about their military achievements. Theirs was a sensitive operation that was held secret from the day it activated, a month before Pearl Harbor was attacked. And a handful of MIS soldiers, like Masao, had quite significant stories to share.

The Military Intelligence Service

The first class of the MIS began in November 1941. The initial location of the MIS Language School, where soldiers were trained in interpretation/interrogation, was housed on the Presidio under a wing of the Fourth Army. The Presidio would become the Western Defense Command hub, with Lieutenant General John DeWitt at the helm, when the US declared war on Japan. When DeWitt ordered the evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry off the west coast, that included the MIS soldiers on the Presidio, even though they were US Army and undergoing training on that very base. The MIS relocated to Minnesota in the spring of 1942. Approximately 6,000 MIS soldiers would be trained; most were sent to communications centers where they intercepted and interpreted Japanese radio chatter and translated documents and books.

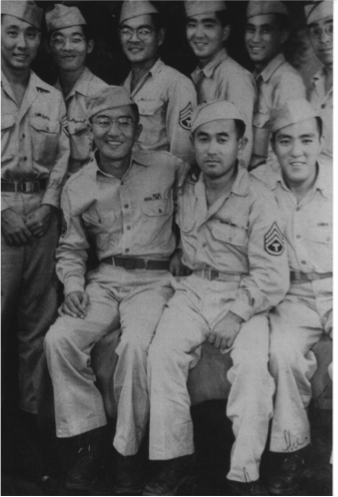

Within the highly sensitive MIS operation was a deeper level of military strategy. A small fraction, as few as 250 of the 6,000 MIS soldiers, were embedded in infantry divisions and served directly in combat in the South Pacific. This was the case with Staff Sergeant Masao Abe who was attached to the 81st Infantry Division.

Considering how much hatred there was toward the Japanese during that time, to be Japanese-American and embedded in a 25,000-soldier, mostly Caucasian infantry division was a dangerous mission at the outset. So dangerous, in fact, that Masao had three bodyguards attached to him at all times. These bodyguards were assigned to protect Masao from Japanese forces, but they were also there to protect him from Allied Forces, including American GIs and Marines.

The mission of the MIS, once on the ground in the South Pacific, was cave flushing. Japanese forces had occupied island chains in the South Pacific prior to the war and had carved out an elaborate labyrinth of tunnels and caves throughout the hills making these islands, such as the Palaus, nearly impenetrable. After the US Navy pummeled enemy strongholds with shell fire, ground troops moved in. Masao, attached to the 321st Regimental Combat Team, along with one other MIS soldier, was in the first wave of soldiers who landed on Angaur.

Masao was assigned to various battalions as they moved through the islands of Angaur and Peleliu to secure caves, humanely interrogate captured Japanese soldiers, gather documents to be translated, and determine military strategy such as ground tactics and the location of Japanese Imperial base camps as well as supply lines.

Amphibious assault on Angaur in the Palau Islands

(Paul J. Mueller Collection, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle, PA)

Masao, an American citizen who had been raised for part of his childhood in Japan, was fluent in speaking, reading, and writing Japanese, and he was utilized to the fullest on battle lines. Masao’s medals speak to his heroics during the war. Among the many medals he earned were: Army Combat Infantryman’s Badge, a Purple Heart Medal, three Bronze Star Medals, three Bronze Battle Stars, one Bronze Arrowhead, an Army Good Conduct Medal, the American Defense Service Medal, an Army Commendation Medal, an American Campaign Medal, an Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and many more.

There was no medal, however, for serving the US in isolation. Masao, and the other MIS soldiers who were on the ground in the South Pacific, served in a unique role. They were soldiers of Japanese descent in the midst of battle with Japanese Imperial forces and surrounded by Allied soldiers, many who had hatred toward any person of Japanese ancestry.

The ten-man Interrogation/Interpretation Team attached to the 81st Infantry Division

Courtesy of the Abe Family

As Masao recalled and shared his action-filled and sometimes poignant stories from World War II, I am reminded about why his is the Greatest Generation. It wasn’t that he was willing to sacrifice his life for his country, as he did with integrity as part of a sensitive and perilous operation. It was that he, like thousands of other Nisei soldiers, served his country with honor while his extended family was interned, even imprisoned, back in the US.

And he, like thousands of others, couldn’t share what he’d endured. For thirty years.

“Never Again,” is a phrase used among Japanese-Americans so that their history, the indignities they and their families once endured, is never repeated. That phrase has recently changed to, “Never Again Is Now.” And the brave MIS soldiers, who waited so many years to share their memories, have an important message: it’s time we remember our history.