Why the Congress of Racial Equality Has Been Forgotten – And Why It Still Matters Today

Marv Rich (left) and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth (SCLC)

Marvin Rich of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) passed on December 29, 2019 in New York City (NYC). A month later, his death has gone unnoticed by any of the local NYC or major newspapers. This is despite the fact that as CORE's second in command during the early to mid-1960's, he was one of the most significant leaders of the Civil Rights movement. He helped lead CORE at its height when many of its members were imprisoned and even killed.

The absence of coverage on Rich's passing speaks to how CORE has often been left out of the history of the Black freedom struggledespite its significant contributions. According to historian Robyn Spencer, CORE "has been the most understudied of the four nationwide civil rights organizations (CORE, SNCC, SCLC, NAACP) associated with the early Black Freedom movement." There are far more books and academic essays on these groups than CORE andCORE's history is frequently left out of academic conferences and public commemorations celebrating the Civil Rights movement.

Even in the history ofits most well-known campaign, the 1961 Freedom Rides, CORE’s role is often diminished in popular accounts. Stanley Nelson's documentary Freedom Riders, for example, depicts the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as the leaders and heroes of the story for stepping in and continuing the Rideswhen CORE’s national office stopped them following the violence in Birmingham, Alabama. Members of New Orleans CORE, however, insist they never quit and were preparing to continue the rides, a side of the story barely heard.

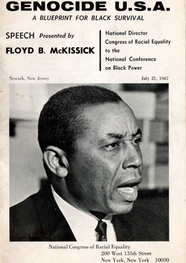

CORE's history as a Black Power organization is even more neglected. While it may not have been the first Black Power group, it was definitelythe second. CORE's national director Floyd McKissick was alongside SNCC head Stokely Carmichael in Mississippi when he made his historic cry for Black Power in 1966. Like SNCC, CORE officially changed from a Civil Rights to a Black Power organization two weeks later at its national convention. It moved away from non-violent direct action and the goal of integration and instead encouraged self-determination and the use of violence in self-defense.

Further, CORE had supported the ideology behind Black Power long before it had a specific name.According to Harlem CORE chairman Roy Innis, Carmichael just gave a name to what many in his and other CORE chapters had already been doing. CORE's involvement in the movement, however, tends to be ignored. For example, the Schomburg Center's recent Black Power 50 book and digital exhibitions neglected to discuss or even mention CORE. This is ironic given that CORE’s headquarters were located right around the corner from the Schomburg on 135th street.

CORE's exclusion from history can be traced back to Roy Innis who succeeded McKissick as national director. Since the 1980s his politics and therefore those of CORE shifted 180 degrees to the extent that he supported the same forces that CORE once opposed such as Rudy Giuliani, Ronald Reagan, both George Bush Senior and Junior. Over time, Innis became known as that Black leader used by the right wing to counter progressive Black leaders. The fact he was successful at it for so long is the problem. In the eyes of former members and scholars, Innis not only ruined his own reputation, he took the entire organization to hell with him. His anti-movement activism and "shenanigans" dirtied the "brand" and made it unattractive. By 1988, Innis' actions were so embarrassing (such as his fist fight on the "Morton Downey, Jr. Show" talk show), it was damn near impossible to give him and by extension CORE any credit for the good he did.

The SNCC Legacy Project partnering with Duke University has worked to create educational programs and make its archival material open to the public online. Unlike groups such as SNCC, however, CORE has no legacy project. This is the other part of the problem. There is no one "pushing the brand." History is political. It requires promotion and marketing. Under Innis, CORE both neglected its own history while rewriting parts of it, added "alternative facts" and took out references to having been a Black Power organization. Former members of CORE have been so demoralized by what Innis has done that they distanced themselves and gave up.

Starting with its sit-ins in 1942, it was CORE that pioneered non-violent direct action paving the way for Civil Rights organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and SNCC. CORE’s tactics, techniques and strategies were adopted and modified by Feminists, Gay Rights activists, Environmentalists, the Stop Mass Incarceration movement, the Occupy Wall Street protests, and Black Lives Matter (BLM).

Once a vanguard protest organization, CORE’s history is significant because it challenges the historiography of the Black freedom struggle by showing how the Civil Rights movement also happened in the north. Racism and the violence that accompanied it was a national issue and not just a southern phenomenon. CORE’s history also speaks to the diversity of the Black Power movement and expands the conversation beyond that of the Black Panthers.

Historian Nishani Frazier argues CORE was the only organization to launch a nationally coordinated attack against Black economic inequality. Her book Harambee City discusses how "CORE attempted to radically restructure cities by transitioning from direct action protest to community development. CORE’s programs acted to stem urban decline by democratizing capitalism." Its Target City project is just one such example of how CORE created a "radical roadmap for economic development."

Another aspect of the Target City project is explored in Rhonda Y. Williams' essay "The Pursuit of Audacious Power Rebel Reformers and Neighborhood Politics in Baltimore, 1966-1968." Her work connects former CORE strategies against housing discrimination to current attempts to increase accessibility and affordability in housing.

My own research focuses on CORE's attempts to transform New York City. In the process CORE created a blueprint for how to get control of local institutions in Black areas. It's focus on community control, independent Black politics, and police brutality has much in common with BLM's action platform.

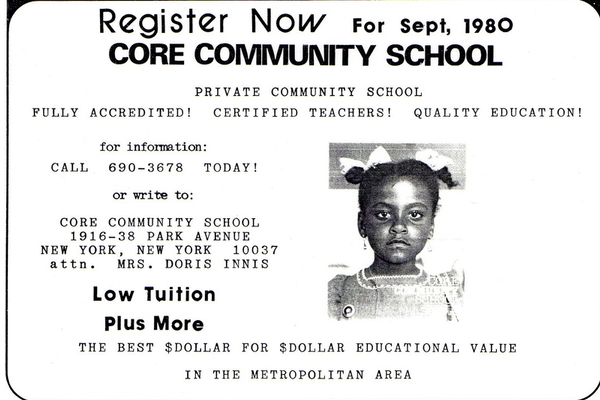

CORE members led the fight for community control of the city's public schools in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn as did Harlem CORE at I.S. 201 and Queens CORE at P.S 40. These demonstrations led to a dramatic increase in the number of Black and Latino teachers and principals as well as the inclusion of Black history in the curriculum. An independent Black school movement evolved as CORE members either founded or played central roles in creating schools such as Uhuru Sasa in Brooklyn, the Dewitt School in lower Manhattan, Central Harlem High School, and the CORE School in the Bronx. Independent Brooklyn CORE created several community based programs with after school tutoring and eventuallyover a dozen senior centers and kindergartens.

CORE members also ran forpolitical office often by creating independent third parties. Many grassroots Blacks won positions ranging from community school board seats to councilmen to state senators. Congressman Major Owens' political career started when Brooklyn CORE created the Brooklyn Freedom Democratic Movement and ran him for city councilman. As part of its Target City program, Cleveland CORE played a central role in getting Carl Stokes elected as the first Black mayor of a major American city.

CORE's anti-police brutality campaigns often made it seem like the fire starter. Its 1964 rallies in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant set off city wide riots and the start of the ‘long hot summers’, the urban rebellions in northern cities across the country during the mid to late 1960s. This led to an immediate increase in the number of Black police officers, captains and commanders. Frazier's book also details how in 1965 Cleveland CORE had its own "counter commissions and investigations into police brutality." "Their activities became part of a larger movement to replace the political powers which selected the local police chief."

At minimum, CORE was a starter kit for Black radicalism. It was through CORE many future Black Power leaders found inspiration and were influenced to start their own organizations and sub-movements. According to Jitu Weusi, a founder of the cultural nationalist organization the EAST and its Uhuru Sasa school, "most of the skills that I obtained in my organizing and organization building came out of my relationship with Brooklyn CORE."

CORE also developed a lasting blueprint for broader social movements. Starting with its sit-ins in 1942, it was CORE that pioneered thenon-violent direct action tactics thatpavedthe way for Civil Rights organizations like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and SNCC. CORE’s strategies for fighting against racial discrimination and organizing around issues are relevant because they are still being used today.CORE’s tactics, techniques and strategies were adopted and modified by Feminists, Gay Rights activists, Environmentalists, the Stop Mass Incarceration movement, the Occupy Wall Street protests, and Black Lives Matter (BLM).

CORE also produced two of the most progressive Presidential candidates in modern times: Jesse Jackson and Senator Bernie Sanders, both of whom started their careers in activism as leaders of their college CORE chapters.

In the larger sense, CORE created models for how people of different ethnicities, religions, and backgrounds can live and work together in peace and harmony thus fulfilling the promise of American democracy, something very much in need of today in a country so hostile to "the other."

Much remains to be learned about CORE. What was happening in CORE that it attracted these activists to begin with? What forces happened within CORE to drive or produce such revolutionary actions? How can these CORE strategies be used today by activists fighting against inequality?

What have we missed by not studying CORE? We need to go back to CORE to have a better understanding of the ongoing antiracist movement and of how our scholarship can help sustainable cities and communities.