Alexander the Great and "The Republic of Northern Macedonia"

The Former Yugoslav Republic Of Macedonia (FYROM) standoff is finally over. The Greek Parliament has agreed that the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia – its name for the country to the northwest of Greece since the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991 – can now be called the Republic of Northern Macedonia. The Greeks had been objecting to the use of the name “Macedonia.” Prefacing “Macedonia” with “Northern,” it turns out, makes all the difference.

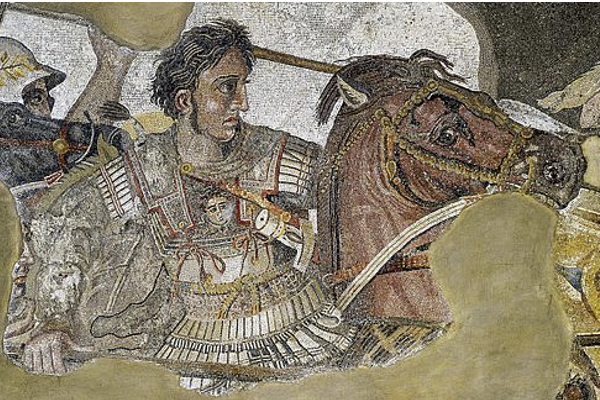

The ultimate source of the problem – or at least the justification for the problem from the Greek perspective – has to be laid at the feet of Philip II of Macedon and, even more squarely, at those of his son Alexander the Great. If father and son hadn’t literally put Macedon on the map, modern day Greeks wouldn’t have been able to claim copyright over the place name. But who were the Macedonians anyway? What was their ethnicity?

During the Greco-Persian Wars, some 2,500 ears ago, an Athenian ambassador in Herodotus’ history states that Greeks are a single people because they share a common language, have common blood, and practice a common religion. We can forget about blood as an indicator of ethnicity because there’s no such thing as racial purity. Likewise, religion is a construct that is only marginally connected with race. So that just leaves language, and that raises a very thorny question: did the Macedonians speak a dialect of Greek, or a separate language, or something in between? They didn’t write literature and they haven’t left us any inscriptions in their own language, so we don’t actually know.

Moving on in time, to 1977 in fact, the Greek archeologist Manolis Andronikos claimed that the artefacts and paintings in what he identified as the tomb of Philip II at Vergina in northern Greece had proven beyond doubt that the ancient Macedonians were Greeks. When he died, Andronikos was awarded a state funeral, in which he was eulogized as “the shield of Greece.” The problem is that the artefacts might have been imported and the tomb painters might not have been Macedonians. So material evidence hasn’t settled the issue either, though it has incontrovertibly demonstrated that Macedon was inside the Greek cultural orbit.

Such complicating niceties are, of course, irrelevant when it comes to the bigger picture of using the past as propaganda. So, what’s in a name? Everything and nothing. But let’s at least praise the Greeks for burying the past.