Robinson Crusoe’s Wall

The question of building a wall on the southern border of the United States has been elevated to a national emergency, despite the objections of national security experts who say that a wall, however long or high, will not secure the border. Opponents of the wall also say that its cost, not only in funds previously allocated for other projects but also in the erosion of our democratic system of government, is not worth the benefit that may be obtained. Yet there is a persistent resolve at the highest levels of government and among a significant number of voters that we must have a wall, no matter what. Perhaps we can look to history, especially literary and cultural history, to explain this passionate desire to build a wall.

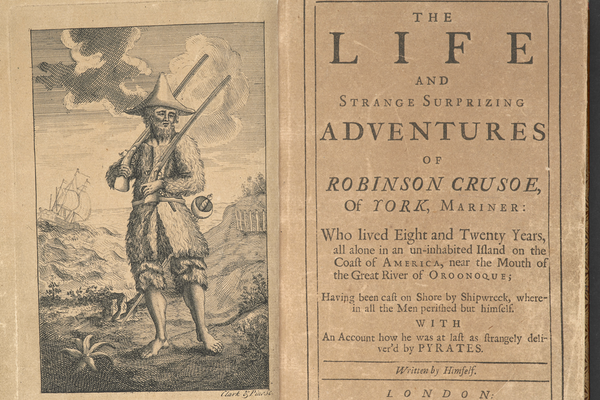

Robinson Crusoe, a novel written by Daniel Defoe in 1719, has much to tell us about walls. In the first century after its publication, Robinson Crusoe became a popular book for children because of the salutary model it was thought to provide for young Englishmen and women. One feature that remained in every edition, no matter how much abridged, was Crusoe’s wall. Thousands of young readers from Britain, America, and many other nations learned from Robinson Crusoe that building a wall was the first step toward creating a civilized domestic space and eventually extending it into an empire.

In the central episode of the novel, the mariner Robinson Crusoe is washed ashore on a deserted island in the Caribbean Sea. To protect himself against wild animals, he builds a wall across the mouth of a cave made of posts set in the earth, backed with layers of turf two feet thick. The wall, a half-circle twenty-four yards in length, takes him fourteen weeks of strenuous labor to build, “but I thought I should never be perfectly secure ’till this Wall was finish’d.”

The completion of the wall enables Crusoe to improve his circumstances, both material and spiritual. He builds a domestic space; he plants crops and raises goats; he reads his Bible and gives thanks for his salvation. But all this security is swept away one day when he discovers a single unfamiliar footprint in the sand. He retreats in terror behind his wall, where he remains for several months. At last he emerges and builds a second wall, “thickened with Pieces of Timber, old Cables, and every Thing I could think of, to make it strong.” This new wall, fortified with seven gunports, can only be climbed with a series of ladders which Crusoe can take down when he is inside his cave. Upon finishing this second wall, he rejoices again in his new sense of security: “I was many a weary Month a finishing [it], and yet never thought my self safe till it was done.”

The object of Crusoe’s terror is the indigenous people of the northeastern coast of South America, then known as Caribs, who visit the island occasionally to celebrate their victories and sacrifice their prisoners. In Defoe’s day it was commonly believed that the Caribs were cannibals, though that point is contested now. Crusoe’s providential rescue of one of their victims, whom he names Friday, allows him to initiate a military-style campaign against the Caribs. Driven by fear and anger, Crusoe attacks the visitors deliberately, not reflecting at first that in doing so “I should be at length no less a Murtherer than they were in being Man-eaters, and perhaps much more so.” Crusoe and Friday kill or wound twenty-one of the “Savages,” whom he implicitly blames for their own deaths.

Crusoe’s last exploit on the island involves assisting in the re-capture of a ship whose crew has mutinied. Instead of hanging the mutineers, Crusoe proposes that they should be marooned on the island, where they may repent and reform themselves as he has done. In effect, he converts his island paradise into a penal colony, leaving the mutineers his cave, his tools, and his wall upon his return to England. On a subsequent visit to the island, years later, he finds that the mutineers have quarreled, fought amongst themselves, and lost their island to the Spaniards. The ending suggests what happens when the lesson of the wall and the purpose it serves are not understood.

Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe suggests that there is nothing better than a wall to provide a sense of security, so long as the wall is a symbol of civic order and domesticity. If those values are lacking, the wall is no better than a penitentiary, locking up disorderly elements within. Before extending the wall on the southern border, we need to decide whether its purpose is to strengthen a civil society, or to perpetuate division and discord on both sides of the wall. If we merely lock ourselves up in our own fear and anger, we are likely to repeat the conclusion of Robinson Crusoe.