When Women Ran Hollywood

Hold on. When did women—who produced only 18 percent of the 100 top-grossing movies of 2018, whose screenplays constituted a mere 15 percent, and who directed a microscopic 4 percent—ever run Hollywood?

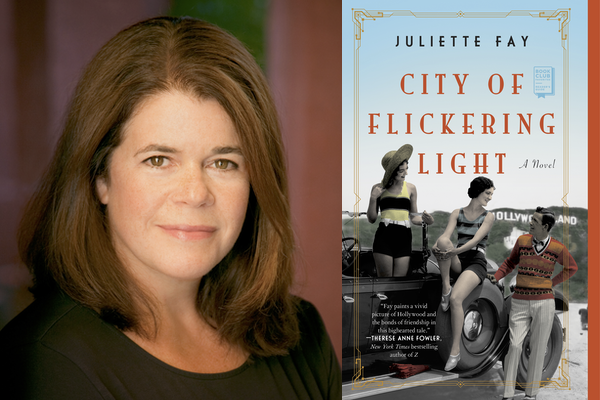

Here’s how I found out about this little-known history. While researching a novel set in 1919 about vaudeville, the live variety shows that were America’s favorite form of entertainment at the time, I learned its demise was caused in part by the growing success of silent movies. The obvious question was, what could make silent movies—with their melodrama, bad acting and, you know, silence—more desirable than a live performance of, for instance, a regurgitator who could swallow and then upchuck items in the order the audience determined? (Audiences loved regurgitation, by the way; also sword swallowing and fire breathing. In addition to a wide variety of acts, there was a lot of ingesting stuff that one just shouldn’t.)

What was so great about silent movies? I soon found myself wandering down a succession of internet rabbit holes. (When it comes to research, most writers can get so rabbit-y we practically sprout long floppy ears.) First, I sampled a few films and found that they were more complex, well-acted, and creatively-filmed than I’d expected. Mary Pickford’s movies or Gloria Swanson’s, for instance, are surprisingly subtle.

But far more fascinating was the fact that women were a driving force in early filmmaking. Up until about 1925, “flickers” weren’t considered terribly respectable, so if you could get a real job, you avoided a career based on these flights of fancy. Conversely, if you were shut out of most employment because of, say, your gender, Hollywood beckoned.

Consider the following:

- Women worked in almost every conceivable position in the industry, from “plasterer molder” (set construction) to producer.

- There were a few popular actors, but actresses were the stars.

- In 1916 the highest salaried director was female.

- In 1922 approximately 40 production companies were headed by women.

- An estimated half of all screenplays produced before 1925 were written by women.

- For over twenty years, the most sought after and highest paid screenwriter was female.

Why had I never heard of any of this? I was familiar with directors D. W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille, producers Sam Goldwyn and Jack Warner, writer-director-actor Charlie Chaplin, but had heard of almost none of the following sample of brilliant and powerful women.

Studio Chiefs

Alice Guy-Blaché began as a secretary for a French motion picture camera company. Fascinated by the medium’s possibilities, in 1896, she asked her boss if she could make a short story film—the first ever!—to promote the camera. He agreed as long as she didn’t shirk her secretarial duties. By the time she moved to America in 1907, she had produced 400 such films. She founded a new studio, Solax, served as president, producer, and chief director, and produced 300 more films by the end of her career. Her feature-length films were quite sophisticated, focusing on subjects of social import such as marriage and gender identity.

Mary Pickford, best known as “America’s Sweetheart,” was the most successful and highest paid actor of her time. She was also a shrewd business woman. Along with D. W. Griffith, Douglas Fairbanks, and Charlie Chaplin, she co-founded United Artists in 1919, and was arguably the most financially astute among them. Chaplin recalls that at a meeting to form the studio, “She knew all the nomenclature: the amortizations and the deferred stocks, etc. She understood all the articles of incorporation, the legal discrepancy on Page 7, Paragraph A, Article 27, and coolly referred to the overlap and contradiction in Paragraph D, Article 24.”

Screenwriters

Known for her sharp wit and snappy dialogue, Anita Loos’ career as a screenwriter, playwright, and novelist spanned from 1912 to the late 1950s. Douglas Fairbanks, as much an athlete as an actor, relied upon her to accelerate his career and devise an ever-expanding list of “spots from which Doug could jump.” Most famously, she adapted her bestselling novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes as a silent film in 1928, which was the basis for the 1953 version starring Marilyn Monroe.

Frances Marion is hard to top even by today’s standards of output and success. Until 1935, well after women’s influence in Hollywood had waned, she remained the most sought after and highest paid screenwriter in America, male or female. She acted, directed, produced, and is the only woman to have won two academy awards for Best Original Screenplay. She was mega-star Mary Pickford’s preferred writer (and best friend) and saved many careers in the tumultuous years when the industry was converting to sound. Above all, Frances was a generous collaborator, hosting famous “hen parties” at her house as a sort of support group for Hollywood’s female filmmakers.

Directors

Lois Weber was also a studio head, producer, screenwriter, and actress, but as a director she was as well-known as D. W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille. In 1916 she was the highest paid director, male or female, earning an unprecedented five thousand a week. She was the first woman member of the Motion Picture Directors Association, with 138 films to her name. They were often morality plays on social issues such as birth control, drug addiction, and urban poverty, particularly as these affected the plight of working class women.

Dorothy Arzner, the most prolific American female director of all time, started in the scenario department in 1919 typing up scripts. In the fluid Hollywood work environment, she quickly progressed to cutting, editing, and writing, and by 1927 had directed her first film. With the advent of sound, she invented the boom mic to allow actors to move about the set without bumping into sound equipment. Arzner was gay and fairly open about her personal life, wearing men’s clothing, and living with choreographer Marion Morgan for 40 years. Despite her gender and orientation, she was able to work steadily as a director until she retired in 1943.

Renowned early film historian Anthony Slide has said, “Women directors were considered equal to, if not better than, their male colleagues.”

Actresses

Florence Lawrence is credited with being the world’s first movie star. In 1908 she was making 100 flickers a year with D. W. Griffith at Biograph, the world’s top studio at the time. However, she was known only as “the Biograph Girl” because the studio didn’t want to increase her burgeoning fame, and thus ability to demand a higher salary, by naming her. She moved to upstart IMP studios, and was involved in perhaps the first wide-scale publicity stunt. The studio quietly fed the papers a story that she’d been killed by a street car, then took out ads declaring “WE NAIL A LIE” claiming that other studios were trying to ruin her career. Fans went crazy for the story, and a public appearance shortly thereafter resulted in mayhem as a huge throng rushed her, pulling buttons from her coat and the hat from her head.

Mabel Normand was a brilliant comic actress, starring in approximately 200 films, most at Mac Sennett’s Keystone studio, and was the first actor to be named in a film’s title (e.g. Mabel’s Lovers in 1912). She also directed many of her own films, including those in which she was featured with a young Charlie Chaplin. Though he erroneously claimed directorship on several of them, Mac Sennett has said that Chaplin “learned [to direct] from Mabel Normand.”

Every one of these women was a multi-talented powerhouse, committed to the success of her films, the industry, and other female filmmakers. And for each of those named above there were many, many more.

Unfortunately, with a few notable exceptions their careers were generally over by the end of the 1920s. As Hollywood historian Cari Beachamp said, “Once talkies arrived, in the late 20s, budgets soon tripled, Wall Street invested heavily, and moviemaking became an industry. Men muscled into high-paying positions, and women were sidelined to the point where, by the 1950s, speakers at Directors Guild meetings began their comments with “Gentlemen and Miss Lupino,” as Ida Lupino was their only female member.”

Their names may no longer be widely recognizable, but these were among the many women who built and ran early Hollywood, shaped the industry in myriad ways, and influenced what we see on the silver screen even today.

Will women ever “run” Hollywood again—or even advance to relatively equal numbers as studio heads, producers, directors, and screen writers? This remains to be seen, of course. But powerful leaders, like executive producer, showrunner, and director Shonda Rhimes, Amazon Studios head Jennifer Salke, Disney TV Studios and ABC Entertainment chair Dana Walden, Producer-director Ava DuVernay, and director Patty Jenkins, among many others, offer hope.

“Demanding what you deserve can feel like a radical act,” Rhimes has said. Radical, perhaps, but not new. All it would take is a return to the good old days of early Hollywood.