Beijing’s Tiananmen Square Massacre

Image: A rally of more than a million people who swarmed the city’s Happy Valley Race Course, to protest the killings. To the right, young Hong Kongers in white (the Chinese color of mourning); to the left, at a private club, indifferent expats enjoy tonics by the pool. By then, many of them had already packed their bags.

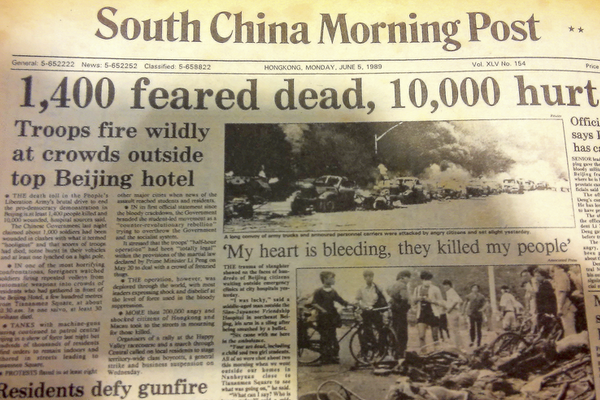

This week marks the 30th anniversary of the infamous June 4th massacre in Beijing — when People’s Liberation Army troops, under the command of the Chinese Communist Party, murdered an unknown number of students in the Chinese capital. Estimates of the death toll range from 200 to 2,500 according to various independent accounts. Most were killed by automatic gun fire, but many were crushed beneath the steel treads of Army tanks.

The sudden, merciless crackdown strangled a blossoming democracy movement led by university students and workers and sent shock waves around the world. But nowhere felt the sheer terror of the mass murders more than the then-British colony of Hong Kong, where I was working as a young reporter.

Knowing that the slaughter in Beijing could happen again in Hong Kong, the city’s confidence in its own future was shattered. For 147 years, Hong Kong was a British colony and had encouraged a free-wheeling capitalist system. It became a showcase of social and economic freedom juxtaposed against the historically brutal communist China. Under British rule, Hong Kong had enjoyed a laissez faire economic system, creating a capitalist economy that was the envy of the world. The people had enjoyed freedoms of the press, speech, assembly and movement in and out of the territory. While local Hong Kong Chinese tycoons had largely run the city’s booming local business community, real political power rested with the governor, who had always been appointed by Britain’s Prime Minister, a situation which suited the Hong Kong Chinese just fine.

Under the terms of the historic 1984 Joint Declaration, signed by Britain and China, the British Crown Colony and its 5.6 million residents would revert to Chinese rule by June 1997. But the prospect of now being under the direct control of the People’s Liberation Army was one which deeply frightened the people of Hong Kong — especially since most of their parents or grandparents had fled China after the communist takeover in 1949.Barring an unforeseen political turnaround by the Beijing regime, experts predicted a massive outflow of people and investments from Hong Kong.

In the weeks leading up to the Beijing bloodbath, and in the dark days that followed, a normally non-political Hong Kong underwent an immense groundswell of cultural pride, and an almost overnight political awakening. As millions marched and swarmed to the city’s early optimistic rallies in proud support of the students’ democratic movement in late May, the long-held belief that Hong Kong people only cared about money was put to rest.

When a crowd of 300,000 packed the city’s Happy Valley Race course on May 27th, where I attended a day-long concert to raise funds for the Beijing students, organizers hoped to raise $250,000. By evening the total take was a generous $3 million.

As the many thousands waved yellow ribbons—borrowed from the 1986 Philippines’ People’s Power Revolution which had toppled Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos— Hong Kong’s leading singers switched from their usual sappy love songs to passionately patriotic tunes such as For Freedom, Heir of the Dragon, Be a Brave Chinese! and Standing as One.

Normally hard-hearted taxi-drivers and mini-van owners refused to accept fares from people heading to the rallies, while street-side fish mongers and vegetable hawkers donated part of their day’s earnings to the Beijing’s students’ democratic movement. All the leading Chinese and English-language newspapers got involved, publishing emotional editorials supporting the aims of the Beijing students. The city’s many glossy magazines replaced the usual pouting pop stars and beauty queens with the handsome face of Beijing student leader Wu’er Kaixi.

But as the days of proud defiance turned into a single night of horror on June 4th, Hong Kong reacted to the Beijing bloodbath with shock, sadness, anger, and finally, outrage. The marches and rallies continued swelling in size to two million. But the mood was now somber and grim. White—the traditional Chinese color of mourning—replaced yellow. And hundreds of marchers—now old as well as young—openly cried in the tropical heat of the teeming streets; something I had never seen before, or since. The public was shaken by the senseless slaughter they’d all seen on television.

The Hong Kong Red Cross pleaded for blood donations for the many injured in Beijing, the call was answered by over 1,000 people per day. Catholic residents of the British territory, including many resident Filipinos, attended a special mass in memory of the slain students, celebrated by Cardinal John Wu and 300 priests. Buddhist services were held in temples across the territory.

In a unique waterborne protest, 200 fishing boats assembled in busy Victoria Harbour, forming the largest flotilla ever seen in Hong Kong. For five hours fishing captains and their crews circled the harbor to pay respects to the young victims of the massacre in China’s ancient capital. Huge black banners, reading “For democracy, for freedom—the fishermen have come!” lay draped across the boats’ wheelhouses.

Newspaper headlines frighteningly alluded to a possible second Chinese civil war. The Hong Kong stock market plunged 300 points—perhaps the sharpest single day fall since 1949. And a massive brain-drain began which eventually grew to a human flood, as close to a million Hong Kong families steadily fledtheir homes. The best and the brightest of the middle-class fled to Australia, Canada, the UK and the United States. The less affluent acquired passports which suddenly became available – for a fee — from remote and obscure poverty-stricken nations in Africa and the South Pacific.

Today, as the world marks the massacre’s 30th anniversary, post-Handover Hong Kong is ruled from Beijing and the city’s 7.6 million people still sit in the historical shadow of that slaughter.

China has never officially released a realistic death toll and Hong Kong stopped asking long ago. Most of the local media is now controlled by Beijing, including the leading English-language newspaper, the South China Morning Post—owned by pro-Beijing billionaire Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba. Even public references to the Tiananmen Square massacre have been watered down – gradually moving to the more politically acceptable “Tiananmen incident.” Or merely mumbled as “Tiananmen…”

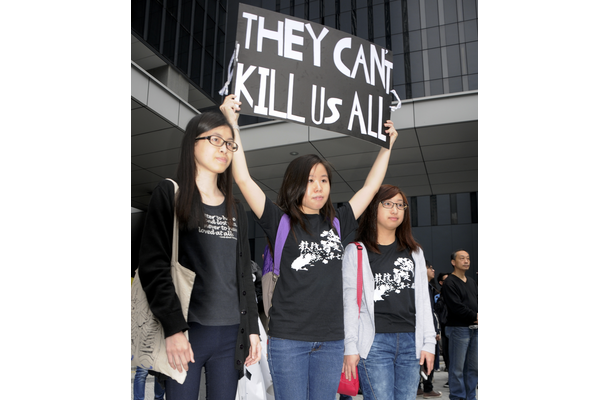

Self-censorship is now rampant in Hong Kong’s once vibrant pressbut sometimes more pressure is applied. In 2014, the editor of Ming Pao—a popular leading liberal paper seen as not supportive enough of Beijing—was attacked on his way to work by several people wielding meat cleavers. He barely survived and will walk with a limp for the rest of his life. Some 13,000 people marched in the streets in protest, and young reporters carried signs reading “You can’t kill us all.”

Beijing is increasingly working to strip away Hong Kong’s freedoms and Hong Kongers have become like the proverbial frog sitting in a pot of water on a stove, where the heat is slowly increased. Beijing has called for Hong Kong’s high court judges to act not as independent magistrates, but as “civil servants” for the government — acting on its behalf rather than that of justice. Two-thirds of the members of the respected 112-year old Law Society of Hong Kong angrily protested. But one-third of the lawyers remained silent.

One poignant pertinent link still binds Hong Kong to the tragic events in Beijing all these years ago: The Goddess of Democracy statue. The original was created by the Beijing students, modeled on America’s Statue of Liberty. It was created in just a few days and made of fragile foam and papier-mâché on a metal frame. It stood 35 feet – designed to be tall enough to be seen from any point in the vast 109-acre Square. The People’s Liberation Army destroyed it on the night of June 4th.

Every year, on June 4th, hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong people remember the Beijing students by gathering for a candle-lit memorial at the city's beloved Victoria Park.

But in 2010, a full-scale bronze replica of the Goddess was created in Hong Kong to become a part of the city’s annual memorial services. These were held in the city’s beloved Victoria Park— in the very heart of the city, where as many as 200,000 people gathered each year. However, after the 2010 gathering, the Hong Kong Government decided to move the politically embarrassing statue to the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s campus, for permanent display—far outside the city.

The hope being: Out of sight, out of mind. Just the way that Beijing wants it.