J. Edgar Hoover’s revenge: Information the FBI once hoped could destroy Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. has been declassified

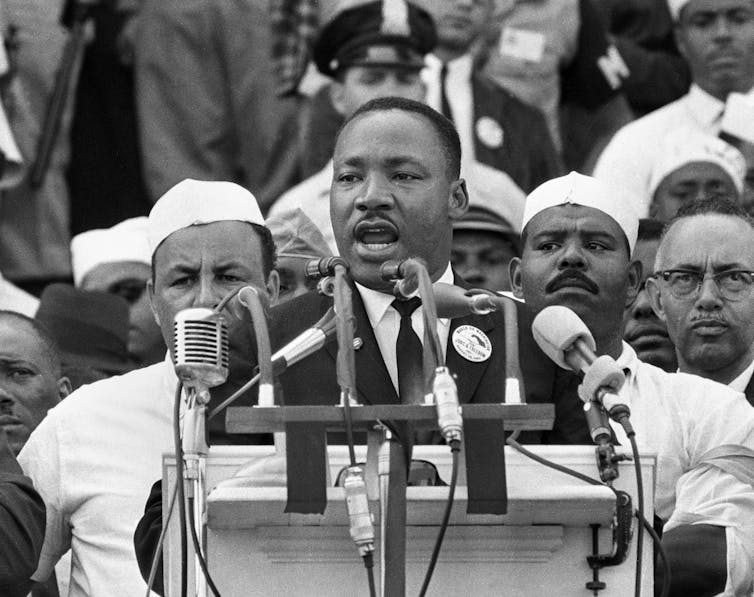

On Aug. 28, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., addresses marchers during his “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. AP/File

Trevor Griffey, University of California, Los Angeles

An article just published by the U.K.-based Standpoint Magazine alleges that civil rights icon Martin Luther King witnessed and even celebrated a woman’s rape.

Written by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David Garrow, one of King’s biographers, the claim relies upon recently declassified Federal Bureau of Investigation documents that summarize tape recordings of King’s extramarital affairs.

The allegation that King witnessed a rape and did not stop it is a serious one. Its impact on how we understand and tell U.S. history, and King’s role in it, is likely to be debated for years.

It’s important to reevaluate King’s legacy in light of this new information.

But as an historian who has done substantial research in FBI files on the black freedom movement, I believe that it’s also important to understand how this information came to be public.

F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover, before testifying at a hearing in Washington, D.C., Sept. 18, 1968. AP/File

Targeting black activism

As director of the FBI from 1924-72, J. Edgar Hoover had an outsized influence on the organization. The FBI operated within the Department of Justice and was tasked with investigating violations of federal law and developing intelligence on foreign agents operating on U.S. soil.

At various points in the 20th century, both Congress and the president instructed the FBI to investigate not just foreign agents but also “radicals” and “subversives.” Hoover interpreted that mandate to also develop what the FBI called “racial intelligence.”

From the 1910s to the 1970s, the FBI treated civil rights activists in general, and African American activists in particular, as either disloyal “subversives” or “dupes” of foreign agents. The FBI’s predecessor, the Bureau of Investigation, sought to “compel black loyalty” during World War I and investigate “negro radicalism” in the 1920s.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the FBI amassed 140,000 pages of documents as part of its investigation of what it called “foreign inspired agitation among American Negroes.” That didn’t even include its files on individual black “subversives” such as civil rights activist Ella Baker, the renowned scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, and the singer and actor Paul Robeson.

And from the late 1930s through the 1970s, the FBI and the House Un-American Activities Committee, through official reports like “The American Negro and the Communist Party,” popularized the notion among conservatives that communists were always trying to use the struggle against racial segregation as a “front” for the “subversion” of individual American liberty.

Focus on King

As Martin Luther King ascended in prominence in the late 1950s and 1960s, it was inevitable that the FBI would investigate him, like it did every other civil rights movement activist, for what it called “communist influence in racial matters.”

King did consult with former members of the Communist Party, among many others. One of his advisers – Stanley Levison – maintained closer ties to the party than he admitted to King, and the FBI knew it.

But it was the civil rights movement’s growing influence that inspired Hoover to become increasingly alarmed about these connections.

Two days after King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, William Sullivan, the FBI’s director of intelligence, famously responded by writing, “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.”

In late 1963, FBI leaders met to discuss ways of “neutralizing King as an effective Negro leader and developing evidence concerning King’s continued dependence on communists for guidance and direction.”

One of those ways for “developing evidence” involved bugging hotel rooms and other places to record King’s conversations with colleagues.

The recordings did not provide evidence of “communist influence” on the civil rights movement. Instead, they recorded King’s extramarital affairs. FBI officials, who already planned to “neutralize” King before they recorded his infidelities, shifted the rationale for their campaign to “morality” without missing a beat.

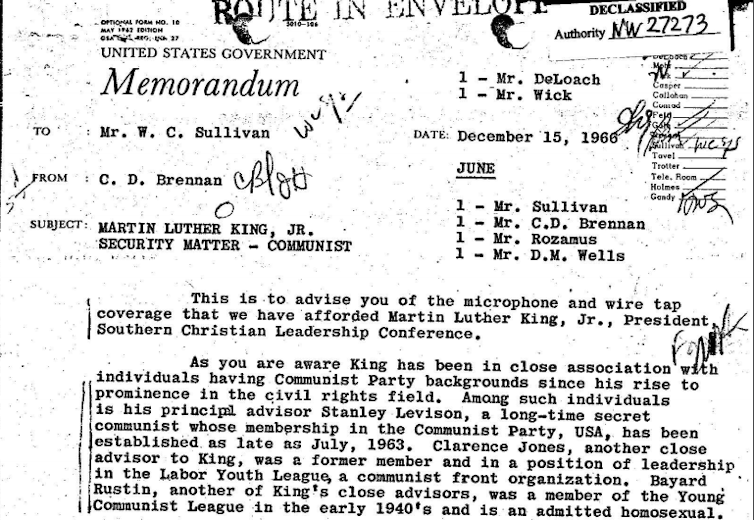

Screenshot from a 1966 FBI memo regarding surveillance of King. National Archives via Trevor Griffey photo

‘Obscene file’

Perhaps surprising to a 21st century reader, policing sexuality had long been part of the FBI’s mission.

The agency had a history of selectively enforcing the Mann Act, the 1910 law that aimed to stem interstate transport of “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” The FBI did this by prosecuting African American men for traveling across state lines with white women. Its “sex deviates” investigation from 1951 through the 1970s produced over 300,000 pages of files as part of what one historian has called “a war on gays.”

FBI agents regularly collected “obscene” materials as part of their investigations, which were then deposited in an “Obscene File” that contained thousands of books, photographs and films by the mid-1960s.

And longtime FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s “Personal and Confidential” files contained what Attorney General Edward Levi described to Congress in 1975 as 48 folders on “public figures and prominent persons… Presidents, executive branch employees and 17 individuals who were members of Congress.”

It wasn’t clear, however, how the FBI could circulate information about King’s affairs without also raising questions as to why the FBI was bugging King’s hotel rooms in the first place. When FBI Assistant Director Courtney Evans recommended in September 1964 that the tapes be destroyed, Hoover overruled him.

Instead, in late 1964, following the passage of the Civil Rights Act and King’s award of the Nobel Peace Prize, the FBI sent excerpts of the recordings to King’s wife, Coretta, along with a letter that encouraged King to commit suicide to avoid having exposure of his extramarital affairs ruin his life.

The stunt failed. In his autobiography, civil rights leader Andrew Young described his and Coretta and Martin Luther King’s responses to the tape that accompanied what he called the “sick letter”: “It was a very poor quality recording. … There was no question in our minds that this scurrilous material was coming from the FBI … few people had the capability of bugging hotel rooms except the FBI.”

Undeterred, the FBI continued to bug King’s hotel rooms from 1965 to 1968, and occasionally circulated memos to the attorney general about the results of the recordings, including both political and sexual topics.

But the FBI didn’t release the tapes themselves, because doing so may have generated the same suspicions raised by the one sent to King.

Dr. Martin Luther King arrives with his wife Coretta Scott King, to deliver the traditional address of the winner of Nobel Peace Prize at the University of Oslo, Dec. 11, 1964. AP/File

Context matters

The preservation of the FBI’s tapes so that they could someday come to light was a political decision made through acts of omission.

When J. Edgar Hoover died in 1972, his secretary Helen Gandy destroyed the FBI’s “Personal and Confidential” files on public officials and celebrities. At the same time, according to Athan Theoharis’ “The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide,” Acting Director Mark Felt incorporated the Bureau’s “Official and Confidential” files into the FBI’s central records system, subject to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Files on King’s private life were placed in this latter set of records rather than destroyed, and some were transferred to the National Archives in 2005.

Litigation by Bernard Lee from King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference sought to compel destruction of the recordings and transcripts. But the judge in the case, John Lewis Smith Jr., rejected the request, and instead ordered them sealed for 50 years until 2027.

People will rightly debate the trustworthiness of FBI sources, and Garrow’s interpretation of them. No figure, no matter how revered, should be immune from scrutiny over their potential support for violence against women.

But those weighing the evidence and its veracity should not forget that the tapes being used to facilitate this discussion were created and preserved with the goal of destroying Martin Luther King’s reputation. The FBI’s intent was to demoralize and fragment the coalition of supporters King brought together in his life, the people who find common purpose by honoring his memory.

In this respect, revealing these materials could be considered “Hoover’s revenge.”

This article has been updated to correct the name of the litigant from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference who sought to compel destruction of the recordings and transcripts.

Trevor Griffey, Lecturer, Labor Studies, University of California, Los Angeles

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.