Why is Brazil so American?

A recent article written by Jordan Brasher about a “Confederate Festival” held in a town in the countryside of São Paulo State, Brazil, drew the attention of readers in the United States. It was not the first time this festival had made the news in America as three years before the New York Times had reported this same event. The difference now is that Brazil is ruled by a new president, Jair Bolsonaro, someone who is becoming renowned for his controversial opinions on race, gender, sexuality and other topics important to various sections of Brazilian civil society. This pulls the “legacy” of the American Confederate movement into the centre of an ethnic-racial discussion at a delicate time in the history of Brazil. To make the situation worse, last May, the president of Brazil visited Texas and saluted the American flag just before giving his speech. Many in the Brazilian media subsequently accused Bolsonaro of being subservient to the U.S.

It may be difficult for an American audience to assimilate this information. After all, apparently, there is not a great deal of convincing evidence within Brazil´s history, language or culture of its affectionate bond towards the U.S.A. However, the truth could not be more different. Since the 18th century, the United Stated has greatly influenced the history of Brazil. Our Northern neighbor gradually became a role model for some of Brazil´s failed independence revolutionary leaders, such as the Minas Gerais Conspiracy.

Nevertheless, it is also true that after gaining independence from Portugal in 1822 the choice for a Monarchic regime diminished the impact of American influence, until November 1889, when Brazil became a Republican Nation and looked upon the U.S. Constitution as its ideal inspiration. This can be both exemplified by the adoption of the Federated Regime, and an introduction of a new name: United States of Brazil (this remained Brazil's name until 1967). At the dawn of this new regime, Americanism inspired our own diplomatic model and even briefly enchanted some of our intelligentsia, especially within the education field.

The 1930s were characterized by a process of modernization of our society with assurance of rights, industrialization and education. This could be considered a kind of Americanism with a Brazilian twist as this process was not led by the civil society but by Getúlio Vargas, an authoritarian ruler of Brazil from 1930 to 1945. Such a modernization required the arrival of immigrants from various parts of Europe, especially from Italy. Thus, in the same way that had happened in the United States, a distorted image of this cultural melting pot has gained traction in the Brazilian identity as a solution for a multiethnic society composed of Indigenous peoples, Europeans and peoples of African descent.

Then, automobile factories arrived and gradually the American inspiration once felt in our political structure spread to the culture sphere. Symbolically, the great ambassador of this transition was the Disney cartoon character, José Carioca, a rhythmic parrot from Rio de Janeiro. Alongside him, Carmen Miranda, who after a long stay in the United States, returned to the Brazilian stage singing: “they said I came back Americanized”. Our Samba began to incorporate elements of Jazz, and Bossa Nova became another vehicle united Brazil and the US, exemplified by the partnership between Tom Jobim and Frank Sinatra.

In the 1970s, a new dictatorship accelerated this process of Americanization of the Brazilian cultural sphere. This was because of the Military´s projects that occupied territories of the West (our version of American expansionism and the “Wild West”), and because it seemed to unleash a more “selfish” type of society. In other words, the project of a development cycle implemented by the Brazilian Military Regime accentuated values such as individualism, consumerism and the idea of self-realization. The self-made man became the norm of our country. As the historian Alberto Aggio points out, “after 20 years of intense transformation of society, Americanism has reached the ‘world of the least affluent’ and because of this the ‘revolution of interests’ has reached the heart of social movements”.

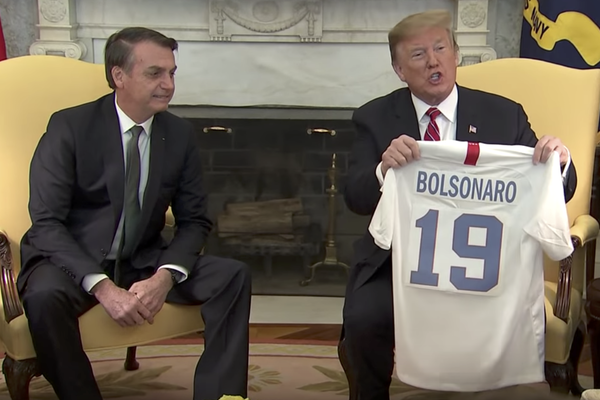

And that was how Brazilian society, from the lowest class up to the highest, became interested in American culture and tried to emulate its habits and cuisine (as we can see in the current “cupcake revolution” in our bakeries), venerated American television series and artists, Americanized children´s names, incorporated words into its vocabulary, and even changed its predilection for sports. For instance, it is not difficult to find a fan of NBA or NFL teams in our country. This is why, though embarrassing, it is fully understandable that our current president, a retired military man from the Brazilian middle class, has this kind of genuine admiration for Trump and his followers.

In addition to the vastness of its territory, its multiethnic identity, the adoption of presidential federalism, industrial modernization and middle classes inspired by the American way of life, there are other elements that bring Brazil closer to the United States. This includes their history of slavery, the racism bequeathed by that despicable practice and its counter legacy of social activism. Starting in the 1930s, the Brazilian black movement tightened its ties with African American intellectuals and activists, which generated exchanges of writings, symbols and experiences of resistance. At first, Brazilians inspired American blacks, especially in the North, but the Civil Rights Movement reversed the terms of influence. The Black Power Movement, particularly the Black Panther Party with its charismatic leaders and affirmative policies, reshaped the Brazilian black movement, as described by Paul Gilroy in his book Black Atlantic. Similarly, transformations in the production of studies on slavery in the United States, beginning in the Civil Rights era, also impacted Brazilian academic studies from the 1980s onwards, inspiring the historiography dedicated to this subject in a decisive way. However, not everything had a positive outcome. The reaction towards the empowerment of subordinate sections of Brazilian society, especially black people, shed light on Brazilian racism that had been veiled until that point. This reveals a difference between Brazil and the USA: while racism has always been somewhat explicit in American culture, in Brazil, the absence of any “WASP pride” and broader adherence to an idealized image of a cultural melting pot society has often led to “informal” demonstrations of racism.For example, the practice of asking a black customer to leave a restaurantat the request of a white customer was common until the 1990s. Thus, on one hand Americanism stimulated a greater struggle for rights and representativeness, yet on the other, it helped bring racism to light.

Regarding the “Confederate Festival”, its origins can be traced back to traditions established by a colony of Southern U.S. immigrants that reached São Paulo State in the late 19th century. However, I would not be surprised if after acknowledging the existence of this Festival, several Brazilians were to spontaneously replicate that “celebration” elsewhere in our country. After all, as the American social scientist and aficionado of Brazil, Richard Morse, once wrote, Latin Americans had the chance to embark on a path to the West without “disenchanting” their culture, in the Weberian sense of the concept. To describe the relationship nurtured by Latin America and the U.S, Morse created a metaphor: a mirror that reflects an inverted image of itself. Apparently, Brazilians got used to being this mirrored version of Northern America. Or put in terms that an Americanized Brazilian, perhaps even Jair Bolsonaro, would understand, we live in a Stranger Things Upside Down of the U.S.