The Washington Nationals Should Stop Letting Teddy Win – He Hated Baseball

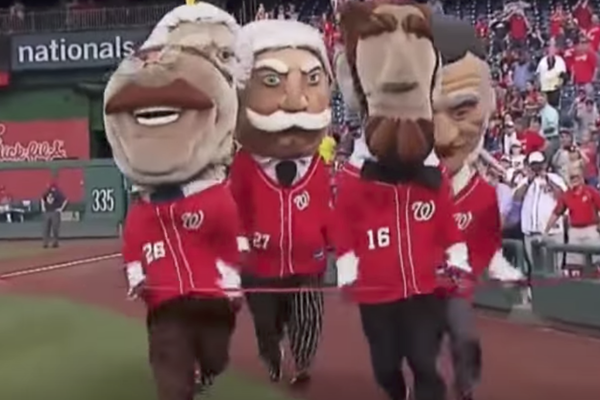

The racing presidents

According to the most recent standings (kept in fastidious detail by LetTeddyWin.com), Theodore Roosevelt’s lead over George Washington is now eight. Thomas Jefferson sits nine wins back. Abraham Lincoln, plagued by a series of poor decisions and stumbles (literally), resides in the cellar.

Confused?

I am, of course, talking about Teddy, the big-headed baseball mascot, Roosevelt. In the middle of the fourth inning at Washington Nationals’ home baseball games, presidential mascots race around the field to the cheers of the District’s baseball patrons. The tradition began in 2006. Usually Roosevelt faces Washington, Jefferson and Lincoln in the no-holds-barred race. Occasionally there are guest competitors. For a few years, the Nationals even introduced lesser presidents (Taft, then Coolidge, then Hoover) into the contest. This trio of interlopers, however, has been retired to the team’s spring training complex in Florida. Now it’s just the Mt. Rushmore quartet, battling it out at every home game—from the frigid first games of April, through the swampy heat of the summer, into the crisp evenings of September.

This presidential mascot race might just been another stadium promotion except for the fact that from 2006 to 2012, TR never won. Like never. He lost 525 consecutive races. Even when Jayson Werth tried to help, TR never crossed the line first.

Ah, what a glorious era of historical karma!

All this losing became made the race a thing in DC. During the last few months of the 2012 season, pressure mounted to let Teddy win at least once. Ken Burns, ESPN’s E:60, and the late Senator John McCain all got involved. An amusing and witty seven minute documentary outlining a “vast left wing conspiracy” meant to keep Teddy from ever winning debuted. The Wall Street Journal put the story on the front page, with a ubiquitous Hedcut picture of Teddy the mascot.

While some poor saps may have actually felt sorry for Teddy, I hope that no historian in good standing with the AHA or OAH was among them. After all, it was Theodore Roosevelt who shunned baseball first.

Baseball’s Great Roosevelt Chase

Theodore Roosevelt romped to reelection (well just election technically, but that’s a different story) in 1904. He won nearly 60 percent of the popular vote. He had become the nation’s first “celebrity president,” connecting with Americans in a new and power way. Recognizing good press when they saw it, baseball’s leaders tried hitch their train to the popular President’s steam engine.

They used simple juxtaposition first. TR and baseball. Baseball and TR. In the 1905 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, which featured a provocative essay on baseball’s origins (Was it possible the game was not uniquely American?), trotted out the Rough Rider angle. “Wellington said that ‘the battle of Waterloo was won on the cricket fields of England,” Spalding’s explained. “President Roosevelt is credited with a somewhat similar statement that ‘the battle of San Juan Hill was won on the base ball and foot ball fields of America.”

The next year’s publication of the popular guide shifted tactics slightly. Baseball was in fact an embodiment of Roosevelt’s “Square Deal.” “When two contesting nines enter upon a match game of Base Ball, they do so with the implied understanding that the struggle between them is to be one in which their respective degrees of skill in handling the bat and ball are alone to be brought into play.” Roosevelt’s “Square Deal,” which had become a “new National Phrase,” was essentially the “Love of Fair Play” that had always been inherent in baseball.

Golden Tickets!

Roosevelt did not attend a single baseball game during his first term in office. Nor in 1904 or 1905. So, in 1906 the American League’s Ban Johnson tried a new approach to get Roosevelt out to the ballpark in the District. “The management has issued a golden pass to President Roosevelt, who may desire to see what a real, strenuous, bold athlete looks like,” the Sporting Life reported in 1906. “Mr. Roosevelt is the first man of the land,” the article continued, “if he sees fit, may adjourn the Senate and both houses and take the whole bunch to the game!”

The golden ticket was just what it sounded like. A ticket laced with gold that allowed the President free entry into any American League game held at the District’s ballpark. And he could bring as many friends as he wanted.

The 1906 season came and went; Roosevelt never used his golden pass.

Undeterred, supporters of baseball tried again as the 1907 season dawned. Although Roosevelt was not particularly susceptible to peer pressure, the Sporting Life and other baseball-friendly dailies mounted a campaign that portrayed Roosevelt as a politician, perhaps the only politician, out of step with overwhelming political support for the game of baseball.

“Chief Justice Harlan, of the Nation’s Highest Court, Plays Base Ball and makes a Home Run in His 74th Year,” trumpeted one headline. “Far from distracting from the dignity of the distinguished incumbent of the Supreme Court seat, the ability of Harlan as a hitter will add to it. That home run is a human touch, a specimen of Americanism that will go far toward popularizing the venerable judge.” Then, just so its readers would not miss the point, the writer posed a rhetorical, shaming question: “How Theodore Roosevelt, who instinctively seems to know how to do the thing that pleases the people, came to overlook the diamond and its opportunities is a mystery.”

The pursuit was getting embarrassing for baseball.

Maybe another, even more golden, ticket would do the trick. The National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues, which eventually become baseball’s minor leagues, decided to step up the pressure on Roosevelt significantly. Rather than just awarding the President a pass to one particular league, for a given season, the NAPBBL invited the President to attend baseball games forever.

The pass presented to Roosevelt on May 16, 1907 at the White House transcended almost every conceivable baseball boundary. The “President’s Pass” covered thirty six leagues and 256 cities; it gave Roosevelt “life membership in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues, with the privilege of admission to all the games played by the clubs composing the association.” The honorary pass was made of solid gold.

And it could do things. The ticket “doubles in two on gold hinges to fold, so that it may be carried in the vest pocket.” The ticket had an engraved picture of the President and the date of presentation, May 16, 1907, on its front. “The photograph of President Roosevelt is beautifully enameled on the fold. The rim is intertwined with delicate chase work. This remarkable card was engraved by Mr. Arthur L. Bradley… It is pronounced by all who have seen it to be a fine piece of artistic workmanship.”

Roosevelt never used it.

Why Teddy, Why?

As Roosevelt left the White House, the Washington Post finally gave up. “With all of his love of outdoor life and sports,” the Post reported in 1909, “Mr. Roosevelt did not go with the ball grounds during his seven years in the White House.”

Why?

“I don’t think that I should be afraid of anything except a baseball coming at me in the dark,” Theodore Roosevelt once said. Readers with a psychological bent can dig deep here, in terms of what Roosevelt was trying to say. But there is a simple explanation as well: Theodore Roosevelt had very poor eyesight. Without the aid of corrective spectacles until his teenage years, Roosevelt never had much of a chance as a young ballplayer.

But why Roosevelt rejected baseball as adult, as a fan, we don’t really know. Roosevelt’s oldest daughter Alice once summed it up as a matter of toughness.

“Father and all us regarded baseball as a mollycoddle game. Tennis, football, lacrosse, boxing, polo, yes – they are violent, which appealed to us. But baseball? Father wouldn’t watch it, not even at Harvard.”

To lose out to tennis on the mollycoddle scale; that hurts.

And Now Teddy is Winning?!

The Nationals caved in 2012. The club let TR break through, in a rather fraudulent manner, on the last day of the regular season. Roosevelt won. What a mistake.

Now, fast forward 7 years, Teddy the mascot is not only winning occasionally, he is leading the season long tally at Nationals’ park. And the Nats, while surging after the All-Star break, are stuck in second place.

So what should the Nats do as they try to chase down the NL East leading Atlanta Braves? While Juan Soto is working hard to make Nats fans forget Bryce Harper and the team’s bullpen might just be getting its act together, I’d suggest the Washington Nationals get their history back in order. Don’t let TR, a noted baseball curmudgeon, win anymore. No mas! Get right with baseball history and perhaps, just maybe, the Nationals will find themselves playing playoff baseball again this October.

For more on Teddy Roosevelt and sports, read Ryan Swanson's latest book: