“The Uplift of All” Through Nonviolent Direct Action

Palo Alto, California

“There is no limit to extending our services to our neighbors across State-made frontiers. God never made those frontiers.” – Mahatma Gandhi

“All men [and women] are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

From street battles in Hong Kong, battlefields of Syria, sweltering refugee camps in Asia and the Middle East, Africa, and Central America, from “every hill and molehill,” as Martin Luther King would say, people demand freedom and want to know, how do we get it? Mahatma Gandhi and King had no monopoly on answers to those questions. Sometimes people have no choice, King said, but to defend themselves, and past movements cannot be replicated. Nonetheless, Gandhi and King did offer a critical, philosophical, strategic and tactical road map to create mass struggles for change. It is called nonviolent direct action.

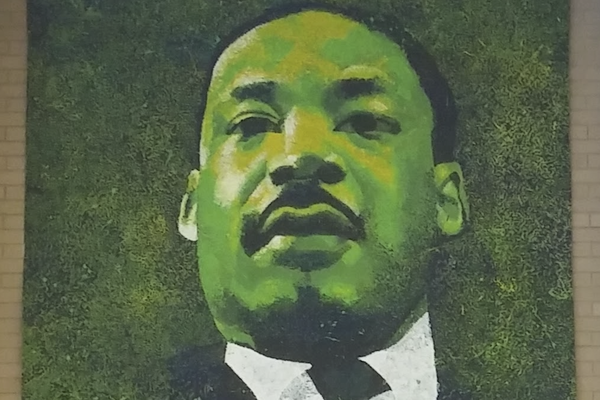

Prompted in part by the 150th anniversary of Gandhi’s birth in 1869, a diverse gathering of hundreds met at Stanford University in mid-October for a conference titled “The Uplift of All: Gandhi, King, and the Global Struggle for Freedom and Justice.” Initiated by Dr. Clayborne Carson, Director of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute, this conference connected us to the Gandhi-King Global Initiative. It includes leaders from both India and the U.S. in an effort “to build an international network of institutions, organizations, and activists committed to the nonviolent struggle for human rights.” Gandhi and King’s broad concerns about war, poverty, environmental crises, and human rights denials often go unspoken, so our gathering sought to bring their full teachings to light, to blend learnings from past nonviolent freedom and justice movements, and to apply them to the twenty-first century.

Highlights included Dr. Carson’s public interviews with descendants of Gandhi, Ela Gandhi and Rajmohan Gandi, whose warm handshake and gentle manner made me feel a direct connection to the Mahatma. Juanita Chavez and Anthony Chavez, descendants of farm worker organizer Cesar Chavez, illustrated how the legacy of nonviolence organizing lives on among Latino/as in California. Martin Luther King III reminded us that, more than ever, human kind faces a choice between “nonviolence and nonexistence.” His daughter Yolanda Renee, who at age 9 had thrilled thousands protesting the murder of students in Parkland, Florida, at the March for Our Lives rally in the nation’s capital last year, affirmed, “I have a dream: this should be a gun-free world.”

Conference participants discussed gun violence, racism and misogyny, war, the global environmental catastrophe, and other crises. A high point of discussion came from Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr., a treasured link to King’s nonviolence philosophy and practical organizing. At ninety-one years of age, Lawson has trained people in nonviolent direct action in civil rights, labor, peace, civil and immigrant rights and other liberation movements from the mid-1950s to the present, highlighting the nonviolent quest to radically reconstruct society without adding more harm. He darkly declared that a “mix of mean spirits” accumulated over generations threatens our existence and that of the planet, but laid out specific examples of how Gandhi’s satyagraha, or “Love in action,” “spirit force,” “soul force,” can create “a force more powerful” than the oppressive forces that dominate the world. He told us that activism by itself is not enough and that movements often fail because they lack a step by step organizing framework. Gandhi focused on ten steps, King on six steps, while Lawson has boiled nonviolent direct action down to four steps. In his model, in-depth, dedicated organizing campaigns often begin with small groups at the local level that create a groundswell for national movements. In that step, which he calls “preparation for nonviolent struggle,” first requires a focus on analyzing issues, deciding who makes decisions, and locating the levers of power to make your opponents say yes when they want to say no. Preparation also includes training in nonviolence discipline and sacrifice that masses can follow when confronting those in power, who always have more weapons. Mary King, Director of the Lawson Institute, directed us to sources on its website, and linked nonviolence efforts back to the 1960s Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

In Lawson’s framework, dedicated organizers need to have a clear plan for direct action with an exit strategy whereby some agreements can be reached and implemented through negotiations to obtain measurable, attainable victories. Without an end point, movements die. To get there, Nonviolence leaves room for reconciliation, without which societies do not move forward. Lawson invokes the force of life we are given at birth that sustains us in order to make nonviolence “a force more powerful.” If his view seems overly optimistic or even naïve, he asks us to range back through history to see that “waging nonviolence” in fact does work and can create lasting change that violence fails to do because it does not resolve underlying issues.

Nonviolence struggle links you backward and forward to generations of people who have changed the world and provides a personal link to others that can sustain a life of activism. “When you help others, you see your doubts in yourself melt away,” the opponent of the death penalty Sister Helen Prejean told us. Lawson’s brother Phillip offered his experiences as a Methodist minister working in black and brown communities facing poverty and violence in the Midwest and the San Francisco Bay area. He felt that putting his life in the service of others, though dangerous, led to a meaningful life. He urged us to create relationships to the poor and the oppressed in whatever ways we can. We are born to die, but the “art of dying” well is grounded in a practice of love that allows you to discover the full sharing of life. “We are not in control, yet life calls on us in various ways to say either yes or no” to action, he said.

As we left the gathering that weekend, I could not sum up what it all meant, but Phillip Lawson’s parting words echoed in my head. “Let loose of the things that bind you and enter into new relationships and each day experience a “newness that bubbles up inside of you.” Whatever the outcome and whatever the hardships, “choose life, wonderful and joyous.”