Elbridge Gerry’s Monster Salamander that Swallows Votes

As Americans prepare to vote in local and state elections on Election Day, tens of thousands--even millions--will find their votes chewed, swallowed, and discarded by a monstrous “salamander”—the two-hundred-year-old creation of Founding Father Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts.

Gerry created the metaphorical salamander to reshape voting districts and ensure his own election and re-election and that of loyal political office holders. The son of a wealthy merchant in Marblehead, Mass., Gerry used his salamander in the 1812 national election, when his friend James Madison announced for the presidency and asked Gerry to run for vice president.

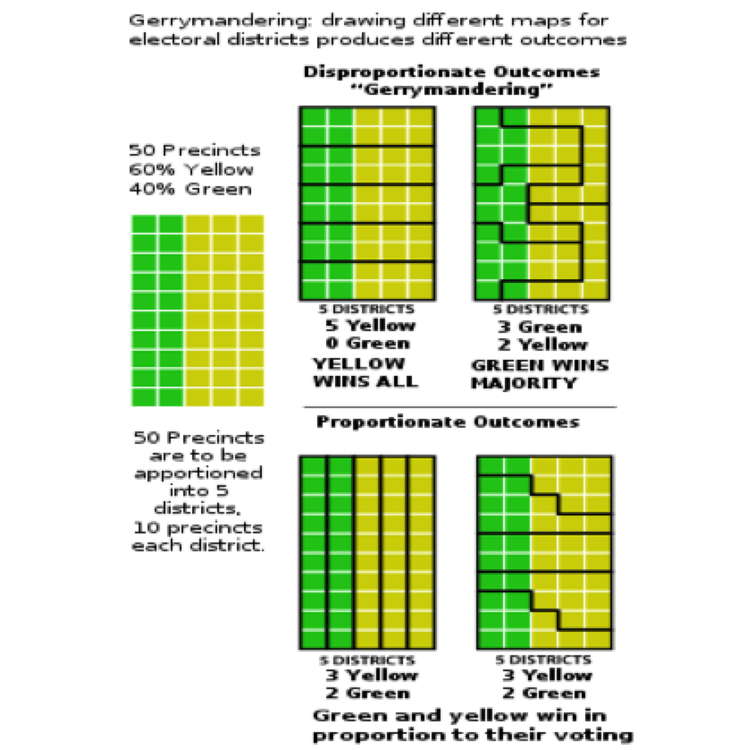

To ensure his victory, Gerry slick-talked a majority of his state’s legislators into redrawing the state’s voting-district boundaries. By extending borders of one district to incorporate larger numbers of opposition voters from neighboring districts, redistricting left selected districts with voter majorities that favored Gerry and ensured his election as America’s fifth vice president

A Boston Centinal cartoonist drew a caricature of what he called the state’s “gerrymandered” districts, with the overpopulated district that opposed Gerry depicted as a monstrous salamander.

A Boston Centinal cartoon in March 1812 shows then-Governor Elbridge Gerry’s creation

of a new salamander-shaped political district that he had “gerrymandered” to favor his political party.

Gerry’s “salamander’ undermined what most Americans believed had been one goal of the American Revolution—elimination of England’s pocket boroughs and rotten boroughs that gave a handful of English noblemen out-sized voting control of Britain’s Parliament. Gerry, however, had not served in the military during the Revolutionary War. Like many signers of the Declaration of Independence, Gerry had supported independence to protect his family’s wealth against British taxation—not to give Americans universal voting privileges.

When the war erupted in Boston, Gerry smuggled food supplies into the city to offset British Army efforts to starve Bostonians for opposing British rule, but he earned handsome profits from the sale of those good—as did other American merchants such as John Hancock and Robert Morris. Few, if any, thought ill of profiting from the war. When polemicist Thomas Paine objected in Congress, Philadelphia merchant Robert Morris retorted, “By becoming a delegate [in the Continental Congress]…I did not relinquish my right of forming mercantile connections.”

With American independence, Gerry refused to sign the Constitution, arguing that executive power over the army gave the president the potential to become a despot. Married and father of thirteen children by then, he told Congress a President with control of a standing army was like “a standing penis: An excellent assurance of domestic tranquility, but a dangerous temptation to foreign adventure.”

With ratification of the Constitution, Gerry ran for and won election to America’s First Congress, where he joined Virginia’s James Madison in winning passage of a Bill of Rights that limited federal government powers to curtail certain individual rights, such as free speech, free press, and the right to assembly.

After two terms in Congress, Gerry served as a diplomat in Paris before becoming governor of his state and then vice president. He died in November 1814, leaving as his principle legacy the powerful and dangerous political weapon of “gerrymandering.”

For more than a century since the Civil War, each political party in almost every state has used and continues to use gerrymandering to strip millions of their voting powers. Leaders in every southern state—Democrats and Republicans alike--gerrymandered for the sole purpose of depriving African-Americans of political influence in local, state, and federal elections. Apart from the impact of racial exclusion in local and state elections, gerrymandering has sent two candidates with fewer votes than their opponents to the White House. Indeed, Donald J. Trump lost the popular vote by an astounding total of more than three million votes, but gerrymandering ensured him 304 of the 538 Electoral College Votes and the presidency of the United States.

In state after state across America, each political party with a legislative majority is now trying to gerrymander to perpetuate its political power. Only a court decision blocked the most recent effort by North Carolina Republicans, and it was not too long ago that voters across the South needed more than five years of massive popular uprisings, rioting, and the lives of men, women, and children to lop off the head of Gerry’s monstrous salamander.

Some gerrymandering of sorts often occurs naturally, without the machinations of scheming politicians. The depopulation of farm areas in many states has given remaining land owners of such districts far more voting clout than voters in heavily populated cities.

The beast will continue to regenerate, therefore, until states or the federal government kill it with legislation that imposes lower limits on district population as a percentage of state population to qualify as an election district.