The Electoral College: How the Founders Cheated You of Your Vote

The U.S. Supreme Court will soon rule on a “college” cheating case, whose outcome will shape the future of America’s presidency and republic. Failure to rule decisively will leave the Electoral College and presidential selection vulnerable to Russian, Chinese, and other foreign government hackers and garden-variety corruption.

The Court will not judge an ordinary college, of course. Its decision will lay down rules for America’s Electoral College, whose votes in December 2020 and every four years thereafter will determine the next President of the United States and shape America’s democracy. Weeks of debate by America’s Founders failed to set any rules at the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia—a failure that led to “cheating” at the College ever since.

The question before the Court is whether Electoral College electors must vote according to the preferences of voters who elected them or whether they may ignore voter preferences and cast votes as they see fit. Twenty-one states allow electors to ignore voter preferences, opening those electors to corruption.

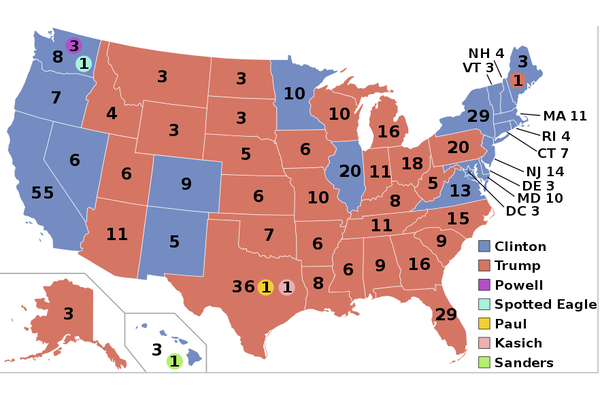

Indeed, “faithless electors” have thwarted voter will in five presidential elections, dating back to 1824. Ten who did so in 2016 were not enough to reverse Clinton-Trump election results, but would have reversed the 2000 presidential election, in which George W. Bush defeated Al Gore by only five electoral votes. A Supreme Court decision to allow electors to ignore voter choices would open the way for a coup d’etat by a despot with control of the nation’s military.

The question of how to choose a president plunged the Constitutional Convention into near-chaos for weeks in the summer of 1787. Almost every delegate offered some plan whose flaws always offset its advantages. Indeed, the original proposal for an Electoral College provoked Virginia planter George Mason to rage that foreign interests would benefit from “the corruptibility of the men chosen.”

Chaired by George Washington, the Convention convened in mid-May 1787, with Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph proposing that “a National Executive be…chosen by the National Legislature [i.e., Congress]” Contrary arguments immediately plunged the Convention into bitter debate. Making matters worse, delegates had sealed Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall) windows to keep proceedings secret, and Philadelphia’s blistering summer heat that sent tempers rising with the temperature.

To Randolph’s motion for Congress to appoint the National Executive, Philadelphia’s Gouverneur Morris snapped that the Executive would become “a mere creature of that body…. Usurpation and tyranny on the part of the legislature will be the consequence.” Morris demanded that “citizens of the U.S.” elect the President.

If the people should elect, they will… prefer some man of distinguished character…of continental reputation. If the Legislature elect, it will be the work of intrigue, of cabal, and of faction. It will be like the election of the pope by a conclave of cardinals; real merit will rarely be the title to the appointment.”

The aging Benjamin Franklin agreed that failure to permit the people to choose the chief magistrate was “contrary to republican principles. In free governments, the rulers are the servants, and the people their superiors and sovereigns.”

Made up largely of America’s wealthiest men, the Convention rejected Franklin’s suggestion. Connecticut’s Roger Sherman claimed the country was too large for a popular vote: “The people will never be sufficiently informed.” South Carolina planter Charles Pinckney agreed, warning that the three most populous states would combine to elect the president and thwart the will of all other states. Nine states agreed and voted down popular elections.

Chaos ensued, with delegates trying to out-shout each other: One called for the House of Representatives to select the President; another for the Senate to do so. “State governors…” cried another; “state legislatures…” “A lottery….”

Washington stood and demanded order!

Maryland lawyer Luther Martin then proposed that electors be appointed by legislatures of each state to select the president. North Carolina’s Hugh Williamson sprang to his feet and objected. Electors “would certainly not be men of the first nor even of the second grade in the states,” because senators, representatives and other federal office holders could not serve as electors. Such undistinguished men, he insisted, would be easy prey for domestic and foreign corruptors. The Convention agreed and rejected Martin’s proposal.

Williamson then proposed giving executive power to three men, each “taken from three districts into which the states should be divided.” A North-South civil war over slavery would be inevitable if a northerner won executive power over the South and vice versa. The Convention believed his proposal thwarted union and made civil war inevitable.

Virginia Governor Randolph charged that all proposals under consideration posed “the danger of monarchy” and “civil war.” The executive “will be in possession of the sword: Make him too weak, the legislature will usurp his powers. Make him too strong, he will usurp on the legislature…..a civil war will ensue, and the commander of the victorious army will be the despot of America.”

As arguing intensified, Washington again barked for order and warned delegates to settle their differences: “There are seeds of discontent in every part of the union ready to produce disorders, if…the present Convention should not be able to devise…a more vigorous and energetic government.”

But Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts gave up: “We seem to be entirely at a loss on this head.”

On August 31, most other delegates also admitted defeat and turned the problem over to a committee of eleven—one member from each participating state--to produce a binding resolution. With six slave-state delegates in the majority, the committee gave each state government power to appoint, directly or by popular vote, “a number of electors equal to the whole number of senators and representatives to which the state may be entitled in Congress.” Those electors would choose the President and Vice President.

Delegates from the North were furious. Three-fifths of the non-voting slaves would inflate the population that determined the number of each southern state’s representatives in Congress, allowing a relatively small number of southern freeholders—the wealthy white plantation and property owners who owned most of the land and slaves in the South—to elect a disproportionately large number of electors to the Electoral College.

The northern delegates, however, recognized that rejection of southern demands would end chances for a constitution and union. Virginia alone was America’s largest, most populous, wealthiest state—the essential core of any union.

On September 12, 1787, the Electoral College was born. In the sixty years that followed George Washington’s election as America’s first president, the South would elect nine of the first twelve presidents, who filled the office for more than forty-eight of those years, until the eve of the Civil War.

The Constitutional Convention left each state free to decide how it would select its electors and whether or not electors would have to cast ballots according to voter preferences. To this day, no federal law prevents electors from disregarding preferences of those who appointed or elected them. In the 230 years since creation of the Electoral College, 214 “faithless electors” have disregarded voter preferences in 19 of 58 presidential elections. The College elected five presidents who failed to win a majority of popular votes. No “faithless electors” have ever been prosecuted.

Although Benjamin Franklin signed the Constitution, he was not enthusiastic: “I confess that I do not entirely approve this Constitution at present, but I am not sure I shall ever approve it.” Washington agreed, conceding imperfections, but citing Article V permitting future amendments to remedy defects.

Washington, however, lived in a nation with fewer than 50,000 eligible voters in a nation of 4 million people and 13 states. He did not--and could not--envision his nation exploding into an empire stretching from the Atlantic Ocean across one-fourth of the planet’s circumference, midway into the Pacific. He did not--and could not--envision a nation of more than 325 million people in 50 states, each with conflicting and often irreconcilable interests.

Despite perennial demands to replace the Electoral College with popular elections, every Congress has refused. Although twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia imposed laws against faithless electors, sanctions range from only token fines to mere nullification of their ballots. Sometime in the coming months, however, the U.S. Supreme Court will rule on whether electors in the Electoral College must obey voters. If it fails to rule or if it rules to free electors of obligations to voters, it will open the Electoral College to foreign government hackers and both foreign and domestic corruption that may end democracy in America as we know it.

[Quotations from the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in this article may be found in The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Edited by Max Farrand (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 4 vols., 1966), II:63-70 (Friday, July 20, 1787) and Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Reported by James Madison (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co., 1987), 331-336.]

For more by the author read: