A President Ready to Pardon

“Mr. President: There’s a military plot to take over the government!”

Those may not have been the words—and probably not even the thoughts—of U.S. Navy Secretary Richard V. Spencer when he confronted President Donald J. Trump after the President pardoned a Navy SEAL for bringing discredit to the armed forces.

But Secretary Spencer’s actual response—and that of SEAL commander Rear Admiral Collin Green--represent the most open flirtations with disregard of presidential orders since General of the Army Douglas Macarthur flouted the policies of President Harry Truman in 1951.

The opening words of a military plot against the American government were fiction, of course—a scene from the 1951 Hollywood thriller Seven Days in May. The statement reflected the discontent in the film’s fictional military establishment with the fictional political establishment. Adding to the film’s tension was the real-life conflict that year between General of the Army Douglas Macarthur and President Harry S. Truman. After Macarthur had publicly criticized the President’s Korean War policies, the President exercised his power as Commander in Chief and fired Macarthur.

Although the dismissal caused some discomfort in the Pentagon and outrage among civilian supporters who revered the general, the Constitution was and is--quite clear: “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States….”

When, therefore, President Donald J. Trump pardoned a U.S. Navy petty officer and ordered the dismissal of U.S. Navy Secretary Richard V. Spencer for defying presidential orders, the President clearly acted within his constitutional rights.

But in doing so, say his critics, the President just-as-clearly violated the spirit, if not the letter, of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, and, they trembled, he may well have undermined military discipline—and conduct--for years. The Navy petty officer committed a crime, and the President pardoned bot man and crime. Moreover, the President had done so twice before—pardoning murders in both cases.

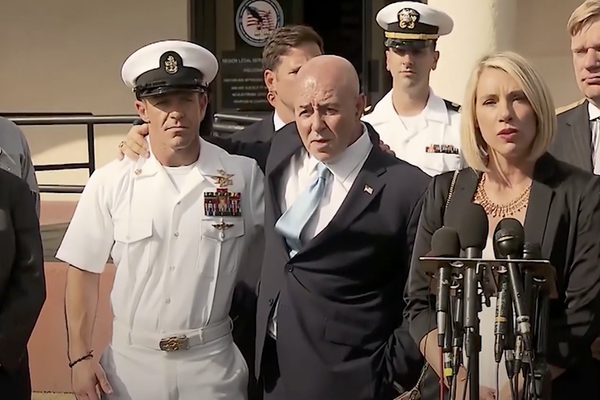

The turmoil the President set loose with his latest pardon began simply enough, with the trial of chief petty officer Edward Gallagher, a Navy SEAL. Accused of shooting Afghan civilians, murdering a captive enemy fighter, posing for photographs by his victim’s body, and threatening fellow SEALs if they reported his misconduct, Gallagher won acquittal on all but one count, for which the court martial demoted him one rank.

The President reversed the decision, but a continuing Navy investigation charged Gallagher with involvement with drugs, and Rear Admiral Colin Green, the SEAL commander, ordered Gallagher expelled and stripped of his prized SEAL insignia. Again, the President intervened, countermanding the admiral and provoking the Navy Secretary’s resignation. Having served as a Marine captain and aviator, Secretary Spencer called the Navy’s actions against Gallagher essential for “good order and discipline.” He responded to the President’s pardon by declaring, “I cannot in good conscience obey an order that I believe violates the oath I took.”

But contrary to his statement, the Secretary’s oath called on him to obey the Constitution, which makes the President commander in chief--even if, like Mr. Trump, the President never served in the military or if his order conflicts with the Uniform Code of Military Conduct (UCMC). In fact, the President is not and cannot be in the military and, ipso facto, is not subject to and cannot violate the UCMC. Indeed, if a member of the military wins election to the presidency, he or she must sever all military ties and cannot wear any uniform in office. (Nor should the President even salute military officers. Doing so is a recent—and incongruous--custom started by President Reagan; it violates both letter and spirit of the Constitution.)

Although critics contend Mr. Trump’s pardons may undermine military discipline, he is not the first President to issue controversial pardons. President Abraham Lincoln routinely pardoned more than 1,500 Union soldiers convicted of desertion. “If almighty God gives a man a cowardly pair legs,” the President chuckled, “how can he help their running away with him?” In one case, Lincoln accompanied his order to release a deserter with the command, “Let him fight instead.”

Not to be outdone, President Andrew Johnson granted full pardons on Christmas day, 1868, to all Confederate troops who fought against the Union in the American Civil War.

A century later, President John F. Kennedy prevented the Army from punishing a soldier for insulting the President, while President Richard M. Nixon commuted the life sentence of 1st Lt. William Calley for leading the Mai Lai massacre of hundreds of Vietnamese citizens in 1968.

And on his first day in office in 1977, President Jimmy Carter infuriated millions of Americans by granting unconditional pardons to hundreds of thousands of men who had evaded the draft during the Vietnam War while hundreds of thousands of less privileged had fought, bled, and died gone in battle.

So President Trump was far from first to issue controversial military pardons. Indeed, the most recent pardon was his third since taking office. Previously, he had pardoned two army officers of murder, and set off a storm of criticism undermining the Uniform Code of Military Conduct.

Such criticism, however, may be based more on politics than military science. With 1.3 million members of the military living in a strictly controlled hierarchy in 150 countries, the likelihood of a single presidential pardon provoking a widespread disciplinary breakdown, let alone mutiny, is beyond remote.