Can America Recapture Its Signature Exuberance?

As the news cycle churns on with impeachment coverage, pundits and politicians are quick to remind that the Constitution is all that stands between us and the whims and dangers of authoritarian rule. It’s a good point, but incomplete. America is a country of law and legend and our founding document, essential as it is, won’t save us if we don’t also buy into a binding story about the point and purpose of our democracy.

That’s a tall order in today’s world. To author Lee Siegel, hacking America’s dour realities is like scaling a rock face. In his recent essay “Why Is America So Depressed?” he suggests we reach for the metaphorical pitons—after “the iron spikes mountain climbers drive into rock to ascend, sometimes hand over hand”—to get a humanistic grip amid our “bitter social antagonisms” and the problems of gun violence, climate crisis and social inequities that have contributed to an alarming rise in rates of anxiety, depression and suicide.

“Work is a piton,” says Siegel. “The enjoyment of art is a piton. Showing kindness to another person is a piton.”

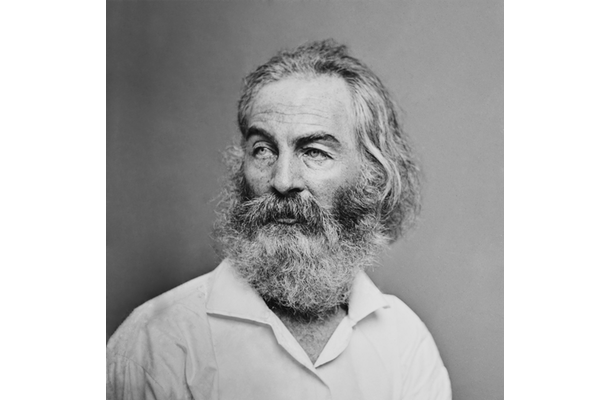

Thanks to Siegel, I now think of the 200-year anniversary of poet Walt Whitman’s birth in the year just ended as a piton for the uplift it gave me. As Ed Simon, a staff writer for The Millions and contributing editor at HNN, declares in another fine essay published New Year’s week, Whitman is “our greatest poet and prophet of democracy.” We’d do well to enlist the bard’s ideas in 2020, he argues, to steer ourselves through “warring ideologies” and to offset “the compelling, if nihilistic, story that authoritarians have told about nationality.”

I would simply add this: Whitman is also the godfather of our national exuberance, a champion of the country’s heaving potential and can-do spirit—traits that, until recently at least, could win grudging regard from some of America’s fiercest critics. Despite his intermittent bouts of depression, Whitman tapped into the energy and brashness of our democratic experiment like no other. His verse hovers drone-like above the landscape, sweeping the manifold particulars of American life into a rapturous, cosmic frame.

Whitman did some of his most inspiring work in the worst of times. He published the first edition of his collection “Leaves of Grass” in 1855 as the country drifted toward civil war. His Homeric imprint, inclusive for its time, invited individuals from varied walks of life (“Workmen and Workwomen!…. I will be even with you and you shall be even with me.”) to splice up with the democratic push to explore contours of the American collective.

My first brush with Whitman’s high spirits came when I was an undergraduate in the late 1960s. Like campuses across the country, the University of Washington was riven by clashing dogmas and muscular protests against the Vietnam War. Like not a few working-class kids brown-bagging it from their family homes, I rode the fence politically, not knowing how to jump. As a citizen, I was offended by club-wielding riot police entering campus in force; as a student of Asian history, I was repulsed watching radical activists trash an Asian studies library, flinging rare old texts out windows onto the grass. Cultural revolution was a tough business.

Lucky for me, a generous English professor, Richard Baldwin, supplied some useful ballast. Sensing my fascination with Emerson, Thoreau and Dickinson, he offered to help me sort out the Transcendentalists during office hours. But it was Whitman who bulled his way forward. His booming energy, delivered in his self-proclaimed “barbaric yawp,” turned me into a forever fanboy.

I loved how Whitman challenged the thou-shalt-nots of established order in “Song of Myself,” joining the role and responsibilities of the individual to humanity’s common lot:

Unscrew the locks from the doors!

Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!

Whoever degrades another degrades me,

And whatever is done or said returns at last to me.

I loved his fervent embrace of democracy in “Democratic Vistas,” his 1871 dispatch to a divided nation:

Did you, too, O friend, suppose democracy was only for elections, for politics, and for a party name? I say democracy is only of use there that it may pass on and come to its flower and fruits in manners, in the highest forms of interaction between men, and their beliefs - in religion, literature, colleges, and schools- democracy in all public and private life … .

I loved his zest for the many-parted American experience, for linking the natural environment to the soul of the country, as he proclaimed his outsized poetic ambition in “Starting from Paumanok”:

… After roaming many lands, lover of populous pavements,

Dweller in Mannahatta my city, or on southern savannas,

Or a soldier camp'd or carrying my knapsack and gun, or a miner

in California,

Or rude in my home in Dakota's woods, my diet meat, my drink

from the spring,

Or withdrawn to muse and meditate in some deep recess,

Far from the clank of crowds intervals passing rapt and happy

Aware of the fresh free giver the flowing Missouri, aware of mighty

Niagara,

Aware of the buffalo herds grazing the plains, the hirsute and

strong-breasted bull,

Of earth, rocks, Fifth-month flowers experienced, stars, rain, snow,

my amaze….

Solitary, singing in the West, I strike up for a New World.

Whitman had his flaws, to be sure. Despite cheerleading for a big-tent America, he also shared the prejudices of his time, blotting his copybook, for example, with ugly remarks about African Americans. By 1969, when I hungered for a healing narrative, the bard’s prescriptions were undergoing reappraisal in light of righteous and long-overlooked storylines offered up by the civil rights and antiwar movements.

Still, Whitman has kept his place in chain of title to America’s resilience. He conveys a panoramic confidence that we are greater as a people than our contemporary realities; that if we lose the thread, we’ll find it again and reweave our story into a new and improved version. As Whitman says in the preface to the 1855 edition of “Leaves of Grass,” people look to the poet “to indicate the path between reality and their souls.”

Thomas Jefferson saw utility in the cohesive national story. In her 2018 book “The Death of Truth,” Michiko Kakutani writes that Jefferson “spoke in his inaugural address of the young country uniting ‘in common efforts for the common good.’ A common purpose and a shared sense of reality mattered because they bound the disparate states and regions together, and they remain essential for conducting a national conversation.”

Today, Kakutani argues, we’re mired in “a kind of homegrown nihilism … partly a by-product of disillusion with a grossly dysfunctional political system that runs on partisan warfare; partly a sense of dislocation in a world reeling from technological change, globalization, and data overload; and partly a reflection of dwindling hopes among the middle class that the basic promises of the American Dream … were achievable … .”

Whitman understood transcendence of national mood is an uphill climb. Periods of division and strife are baked into our democracy, part of the yin and yang, the theory goes, that sorts new realities into a renovated sense of purpose. Yet periods of upheaval must necessarily lead to a refitting, not obliteration, of our common story or democracy is toast.

Do Americans still have the chops to reimagine the song of ourselves?

Lord knows, we’ve had the chops. In his 1995 book “The End of Education,” media critic Neil Postman writes: “Our genius lies in our capacity to make meaning through the creation of narratives that give point to our labors, exalt our history, elucidate the present, and give direction to our future. ”But we do have to mobilize the genius.

That’s easier said than done in a time brimming with distraction, distress and division. It’s hard to say when or if we’ll devise a story with the oomph necessary to yank us up and over the walls of our gated communities of the mind—toward efforts that will make society more inclusive, the economy more equitable and life on the planet more sustainable.

In the meantime, three cheers for the ebullient currents of American life Walt Whitman chronicled. On our best days, they can lift us above our brattish, self-defeating ways.