Trump Checks all of the Impeachment Boxes: Will it Matter?

In my last article, I wrote that there is something wholly different about Donald Trump’s actions than those of other presidents who have exceeded their power. Why? Unlike other presidents, Trump’s actions meet each of the requirements that the Framer’s laid out to impeach a president. Ironically, just as impeachment is needed most, the partisan tenor of the times may make it impossible to accomplish.

The Framers of the Constitution had included the power of impeachment for instances of treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors committed by executive branch officials and the president. They had rejected policy disputes as a basis for impeachment. When George Mason proposed adding maladministration as an impeachable offense, Madison responded that “so vague a term will be equivalent to tenure during pleasure of the Senate.” It was at this point that “high crimes and misdemeanors” were added. While the first two are clear, the third sounds vague to us today. Yet, the Framers had a clear idea of what this meant. As I wrote previously for the History News Network, the Framers “thought that the power of impeachment should be reserved for abuses of power, especially those that involved elections, the role of foreign interference, and actions that place personal interest above the public good” which fall within the definition of high crimes and misdemeanors. Professor Noah Feldman of Harvard Law School, in his testimony to the House Judiciary Committee, said that for the Framers “the essential definition of high crimes and misdemeanors is the abuse of office” by a president, of using “the power of his office to gain personal advantage.” Trump’s actions with Ukraine checks each of these boxes.

Presidents and Congress have often found themselves in conflict, dating back to the earliest days of our Republic. Part of this is inevitable, built into a constitutional system of separation of powers with overlapping functions between the two branches. Only Congress can pass laws, but presidents can veto them. Presidents can negotiate treaties but must obtain the advice and consent of the Senate. As Arthur Schlesinger Jr. observed, checks and balances also make our political system subject to inertia. The system only really works “in response to vigorous presidential leadership,” Schlesinger wrote in The Imperial Presidency. But sometimes presidents grasp for powers that fall outside of the normal types of Constitutional disputes. This is where impeachment enters the picture.

In the early Republic, disputes between presidents and congress revolved around the veto power. Andrew Jackson was censured by the Senate over his veto of bank legislation and his subsequent removal of federal deposits from the Second Bank of the United States. Jackson’s actions showed a willingness to grab power and to ignore the law and the system of checks and balances when it suited his purposes. While the censure motion passed, it did not have the force of law. It was also unlikely that impeachment would have been successful, since the dispute was over policy. While the president had violated the law, not all illegal acts are impeachable. As Lawrence Tribe and Joshua Matz have noted, “nearly every president has used power in illegal ways.” Impeachment is meant to be limited to those actions, like treason and bribery, “that risk grave injury to the nation.”

Congress considered impeaching John Tyler in 1842 over policy disputes for which he too used the veto power. Tyler is sometimes referred to as the accidental president since he assumed the presidency when William Henry Harrison died in office one month after he was sworn in. Tyler had previously been a Democrat and state’s-rights champion who had joined the Whig Party over disagreements with Jackson’s use of presidential power. Yet he preceded to use the powers of the presidency to advance his own policy views, and not those of his newly adopted Whig Party, vetoing major bills favored by the Whigs, which led to an impeachment inquiry. A House Committee led by John Quincy Adams issued a report that found the President had engaged in “offenses of the gravest nature” but did not recommend that Tyler be impeached.

Even Andrew’s Johnson’s impeachment largely revolved around policy disputes, albeit extremely important ones. Johnson was a pro-Union southerner who was selected by Lincoln to aid in his reelection effort in 1864. Johnson was clearly a racist, a member of the lowest rung of southern white society, those that felt their social position was threatened by the advancement of blacks, a view that shaped Johnson’s policies on Reconstruction. While the Civil War ended slavery, it did not end the discussion of race and who can be an American. Johnson, much like Trump, represented those who believed that America was a typical nation, made up of one racial group. “I am for a white man’s government in America,” he said during the war. On the other hand, the Radical Republicans believed that America was essentially a nation dedicated to liberty and equality, and they set out to fulfill the promise of the American Creed for all American men, black as well as white. This was the underlying tension during the period of Reconstruction. “Johnson preferred what he called Restoration to Reconstruction, welcoming the white citizenry in the South back into the Union at the expense of the freed blacks,” Joseph Ellis writes.

But Johnson was ultimately impeached on false pretenses, not for his policy disputes with Congress, but due to his violation of the Tenure of Office Act, which some have characterized as an impeachment trap. The act denied the president the power to fire executive branch officials until a Senate confirmed appointment had been made. While the House impeached Johnson, he escaped removal by one vote in the Senate. Johnson’s sin was egregious; he had violated one of the core tenants of the American Creed, that all are created equal. Yet this did not rise to the level of an impeachable offense that warranted the removal of a president. It was a policy dispute, one that went to the core of who we are as Americans, but it was not a high crime or misdemeanor.

It would be over one hundred years before impeachment would be considered again, this time in the case of Richard Nixon. Like Trump, Nixon abused the power of his office to advance his own reelection. Both men shared a sense that the president has unlimited power. Nixon famously told David Frost that “when the president does it, that means its not illegal,” while Trump has claimed that under Article II “I have the right to do whatever I want. But Nixon, unlike Trump, did not elicit foreign interference in his reelection effort. The two men also shared certain personality traits that led to the problems they experienced in office. As the political scientist James David Barber wrote in his book The Presidential Character, Richard Nixon was an active-negative president, one who had “a persistent problem in managing his aggressive feelings” and who attempted to “achieve and hold power” at any cost. Trump too fits this pattern, sharing with Nixon a predilection toward “singlehanded decision making,” a leader who thrives on conflict.

Indeed, Nixon would likely have gotten away with Watergate except for the tapes that documented in detail his role in covering up the “third rate burglary” that occurred of the Democratic Party headquarters on June 17, 1972. Paranoid about possibly losing another election, Nixon had directed his staff to use “a dirty tricks campaign linked to his reelection bid in 1972,” presidential historian Timothy Naftali has written. When the break in was discovered, Nixon then engaged in a systematic cover-up, going so far as to tell the CIA to get the FBI to back off the investigation of the break in on bogus national security grounds.

Much like Trump, Nixon stonewalled the various investigations into his actions, what Naftali calls “deceptive cooperation.” He had the Watergate Special Prosecutor, Archibald Cox, fired in October 1973 in order to conceal the tapes, knowing his presidency was over once they were revealed. In the aftermath of Cox’s firing during the so-called Saturday Night Massacre, Nixon refused to release the tapes to the House’s impeachment inquiry. Instead, he provided a transcript he had personally edited that was highly misleading. The final brick in Nixon’s wall of obstruction was removed when the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in July 1974 that Nixon had to release the tapes, which he complied with. One wonders if Trump would do the same.

One difference with the Trump case is that there was a degree of bipartisanship during the Nixon impeachment process. By the early summer of 1974, cracks had begun to appear in the Republicans support for Nixon. Unlike today, there were still moderate Republicans who were appalled by Nixon’s actions and had become convinced that the president had engineered a cover-up. Peter Rodino, the Democratic chairman of the House Judiciary, had bent over backwards to appeal to the moderate Republicans and to Southern Democrats, where Nixon was popular. Despite strong pressure from the leadership of the GOP in the House, it was this group that ultimately drew up the articles of impeachment.

Still, a large number of Republicans in the House continued to stick with the president until the tapes were finally released. It was at this point that even die-hard Nixon supporters deserted him when it became apparent that Nixon had been lying all along and had committed a crime. Nixon’s case shows both the importance of bipartisanship in the impeachments process, but also how difficult it is for members of the president’s party to turn on him. In August of 1974, Nixon resigned when confronted by a group of Senators and House members, led by conservative Senator Barry Goldwater.

The impeachment of Bill Clinton is the anomaly, since it was not about policy (as in Johnson’s case) or the abuse of power (in Nixon’s case). Rather it emerged in part due to a character flaw. Clinton could not restrain himself when it came to women.

The facts of the case are well known. While president, Clinton had an illicit sexual encounter with Monica Lewinski in the Oval Office. He then proceeded to lie about it, both to the country and also during a deposition in the Paula Jones case, and attempted to cover up the affair. Kenneth Starr, who had been appointed as Independent Counsel to investigate the Whitewater matter, a failed land deal in which the Clinton’s lost money but did not nothing wrong, then turned his investigation to the president’s actions with Lewinski and recommended that the House of Representative consider impeachment proceedings for perjury and obstruction of justice.

By this point, Clinton had admitted he had lied to the country and apologized for his actions. The House had the opportunity to censure Clinton, but Tom Delay, one of the Republican leaders, buried that attempt, even in the aftermath of the midterm elections when Democrats gained seats, clearly pointing to public opposition to impeachment of the president, whose approval rating were going up. While the House voted for impeachment largely along partisan lines, the Senate easily acquitted Clinton on a bi-partisan basis. Clinton’s actions, while “indefensible, outrageous, unforgiveable, shameless,” as his own attorney described them, did not rise to the level the Framers’ had established for impeachment.

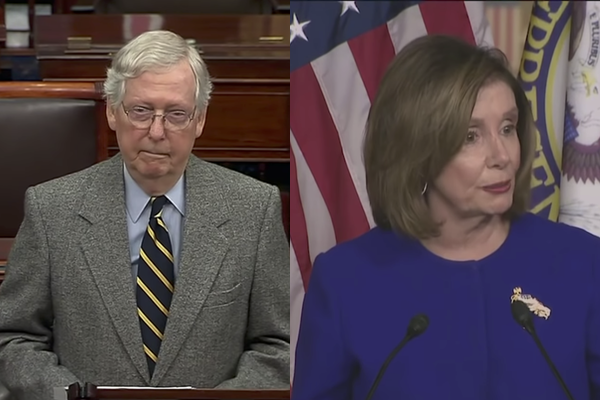

Clinton’s impeachment in the House was largely a product of partisan politics that were out of control. As Lawrence Tribe and Joshua Matz have written, “starting in the mid-1990’s and continuing through the present, we’ve seen the creeping emergence of a permanent impeachment campaign.” Both George W. Bush and Barack Obama faced impeachment movements during their terms in office over issues that in the past no one would have considered impeachable. During the 2016 election, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump lobbed accusations that the other would face impeachment if elected. The current toxic political environment raises the issue of whether a bipartisan impeachment effort has any chance at all, especially when the two sides cannot even agree over basic facts. Nancy Pelosi was right to hold off the movement to impeach Trump prior to the Ukrainian matter, but now that we have such a clear abuse of power, what is the alternative? At this moment, when the tool of impeachment is most needed for a president who meets all of the criteria laid out by the Framers, the process itself has become captive to extreme partisanship by the Republicans.

The ball is now in the Senate’s court, where the trial will soon occur. While conviction and removal from office is highly unlikely short of additional corroborating evidence (which Mitch McConnell has been attempting to squelch), perhaps the Senate can find the will to issue a bipartisan censure motion that condemns the president and issues a warning that another similar abuse of power will result in removal. Ultimately, the voters will likely decide Trump’s fate come November. We can only hope they choose correctly.